ABOUT 50 km north of Oamaru, the subject of last week’s post, there is the similarly named town of Timaru.

The journey from Oamaru to Timaru makes for quite an interesting road trip, by way of the village of Glenavy and the slightly inland town of Waimate, and I will be doing a blog about this road trip a bit later. But this one is strictly about Timaru.

Timaru sits at the southern end of the Canterbury Plains and the sweeping coastline of the Canterbury Bight. Its strategic location led the town’s Victorian-era colonists to build an artificial harbour, which can be seen in the aerial photograph below.

The harbour’s breakwater, which has been transformed into a rectangular wharf in more recent times, created an artificial bay to its north. This bay came to be known as Caroline Bay.

Though it had been a rocky shore when the harbour was built, Caroline Bay soon filled up with sand and became a city beach.

Indeed, Caroline Bay soon became an important beach resort, championed as the Riviera of the South Island (or even of New Zealand), in much the same way as Napier in the North Island.

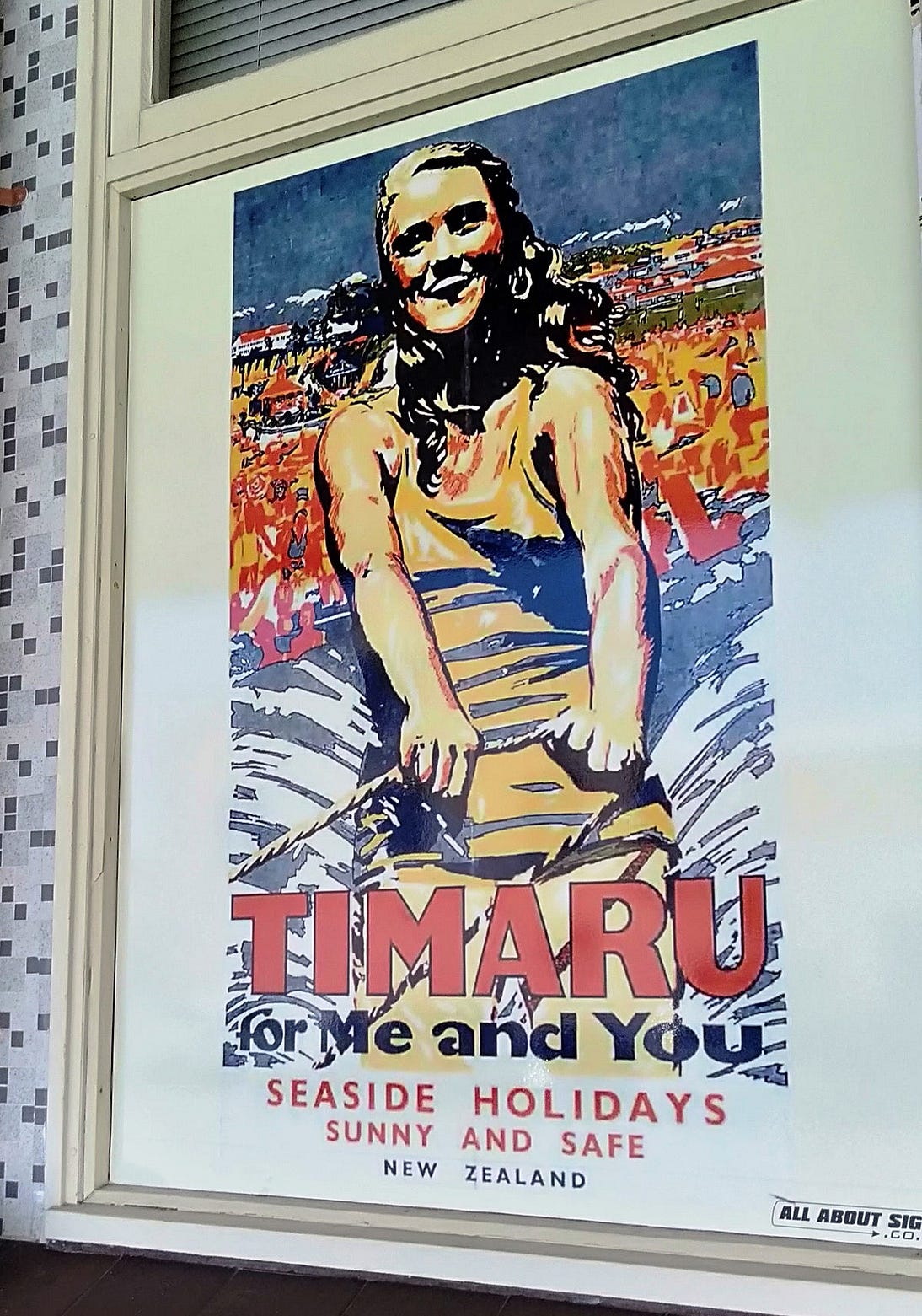

A few years ago, I photographed the following posters, which look like they date back to the 1930s.

You can buy them to stick on your wall at Timaru’s South Canterbury Museum, which I have to say is one of the best small museums I’ve seen.

Here’s a panorama of Caroline Bay and its scenic reserve, which was redeveloped in the early 2000s, filmed from the Bay Hill: a notable strip of cafés and restaurants just above it.

The mountains behind the town, snow-capped in winter, can be seen clearly from the Bay Hill as well.

The next photo shows a sculpture, installed in 2008, called the Face of Peace, by Margriet Windhausen, which apparently “glows in the afternoon sun.” I must go back and get a photo in sunny weather!

I also took in a performance at Caroline Bay’s soundshell. There are similarities with Napier in that sense, including a street called Marine Parade.

As in Oamaru, there are little blue penguins, or kororā, nesting by the wharf at the southern end of Caroline Bay: see timarupenguins.co.nz/.

Timaru lies on undulating terrain, made from lava flows that once cascaded from a nearby extinct volcano called Mount Horrible. The basalt lava of Mount Horrible is called ‘bluestone’.

Along with smaller quantities of granite from the same volcano, Mount Horrible bluestone was used to build the colonial town in just the same way that Oamaru was built out of local ‘whitestone’.

As Oamaru is whitestone, so Timaru is bluestone, though in practice there is often a mixture, as with St Mary’s Anglican Church, one of several magnificent churches that still dominate Timaru’s skyline.

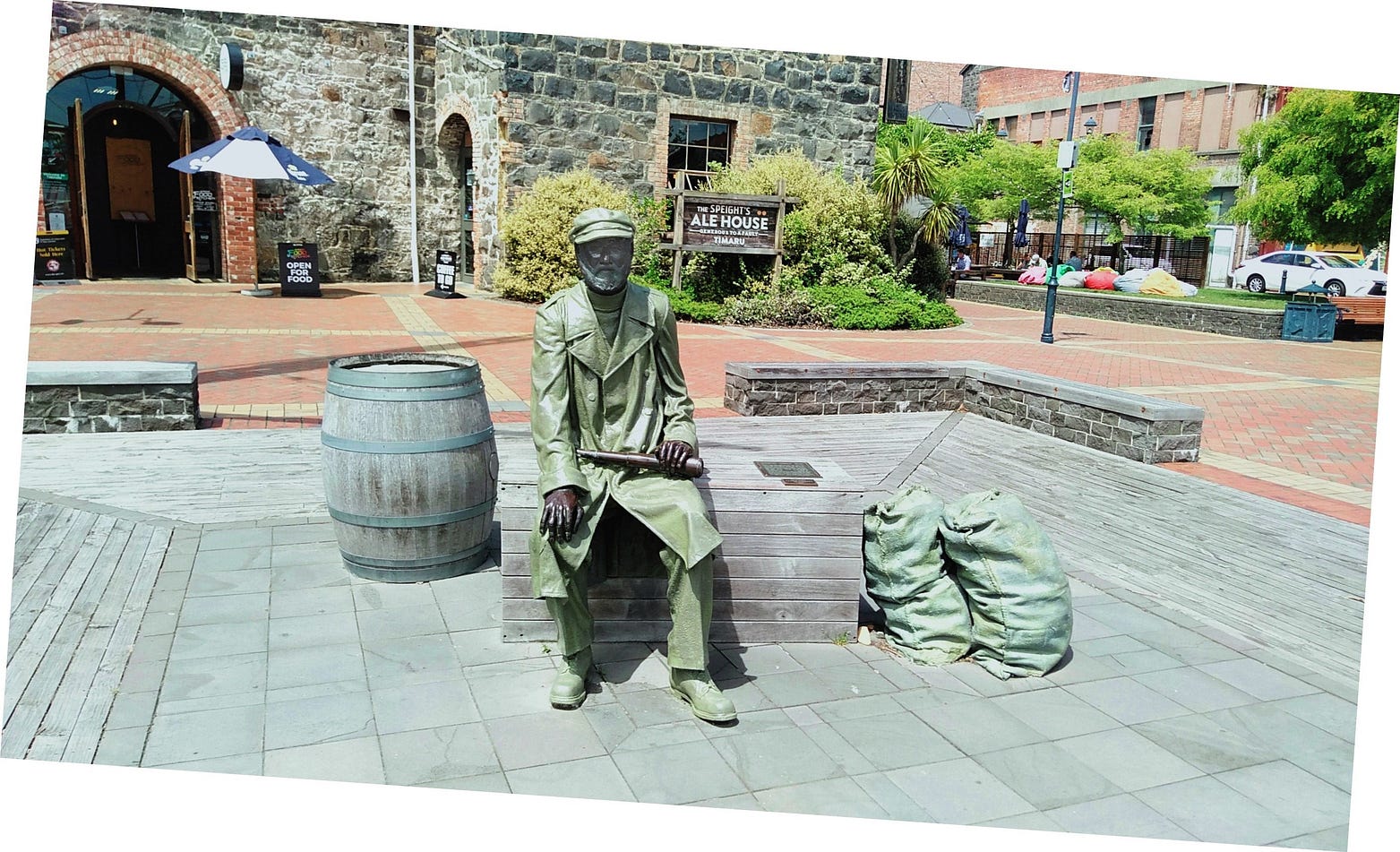

Some of the bluest bluestone I saw was that of the old waterfront building that now houses the Timaru iSite, or tourist information centre, and the Speight’s Alehouse.

Unlike Oamaru, Timaru is still a working port. A gritty industrial architecture combines older buildings with newer ones.

And a monument to seafarers.

In keeping with the town’s old-fashioned qualities, church spires and landmark public buildings tend to be the tallest features on the skyline. Here’s a photo of the town hall, snapped from inside a car at dusk.

The twin towers of the Roman Catholic Basilica are among the most prominent landmarks.

You can see the Basilica in the background of the next photo, which is of the former Bank Street Methodist Church, a listed historic building that has been used as a funeral chapel since 1992. The spire is very simple, but the weathered green copper really stands out.

The tower of St Mary’s Anglican is at the opposite end of the ornateness scale.

Another striking spire is that of the Chalmers (Presbyterian) Church, restored at the beginning of the 21st century. The Chalmers spire is covered in zinc tiles that gleam blindingly in the sun.

The Chalmers Church also has elaborate stained-glass windows (unusual for a Presbyterian church, apparently). You can see St Mary’s behind the Chalmers Church in the next photo, and the town hall behind St Mary’s.

Here’s a view down one of the main streets, showing the former Bank Street Methodist Church, the Chalmers Church, and St Mary’s, all in one glance. This is very much the way our towns used to look, before the blight of tall office buildings caught on.

A bit more modern is the Timaru Library at 56 Sophia Street, located in a building designed by the notable modern architects Warren and Mahoney, of Christchurch, and opened in 1979. It has a couple of large tourist information panels in front. Behind the information panels you can see the bronze busts of a couple of Timaruvians who attained high British military ranks, Second Lord of the Admiralty Sir Gordon Tait and Marshal of the Royal Air Force Lord Elworthy.

In fact, there is an amazingly long list of distinguished people from Timaru and nighbouring districts, their biographies maintained in the local council’s Hall of Fame.

Here’s a view from the same spot, looking in the other direction. Along with the iSite on the waterfront, this is a good place to get directions.

And here’s another interesting building I came across during some festivities a few years ago: the Dominion Hotel, now a backpacker hostel.

‘Hotel’ is a New Zealand euphemism for a liquor establishment dating back to the days when the clamour for Prohibition was strong, a clamour mixed in with prejudice against the allegedly hard-drinking Catholic Irish.

Things didn’t go quite as far as in the USA, but even so, from World War One until 1967, New Zealand’s public bars had to close at 6 pm, which didn’t leave much time for drinking if you got off work at 5 (that was, of course, the idea).

On the other hand, hotel guests were allowed to go on imbibing till late in the hotel’s private bar, along with anyone else who might be mistaken for a hotel guest.

Many bars thus added a storey or two and became hotels. These new hotels also gained ultra-respectable names such as the Dominion, the Royal George, the Naval and Family, the Edinburgh Castle, and so on.

Like most New Zealand towns, Timaru has a lot of parks. The great parkland at Caroline Bay is the most visible, but other famous parks include Centennial Park, on the western outskirts of the town.

And the Timaru Botanic Gardens, which lie in a dell with a lake at the bottom.

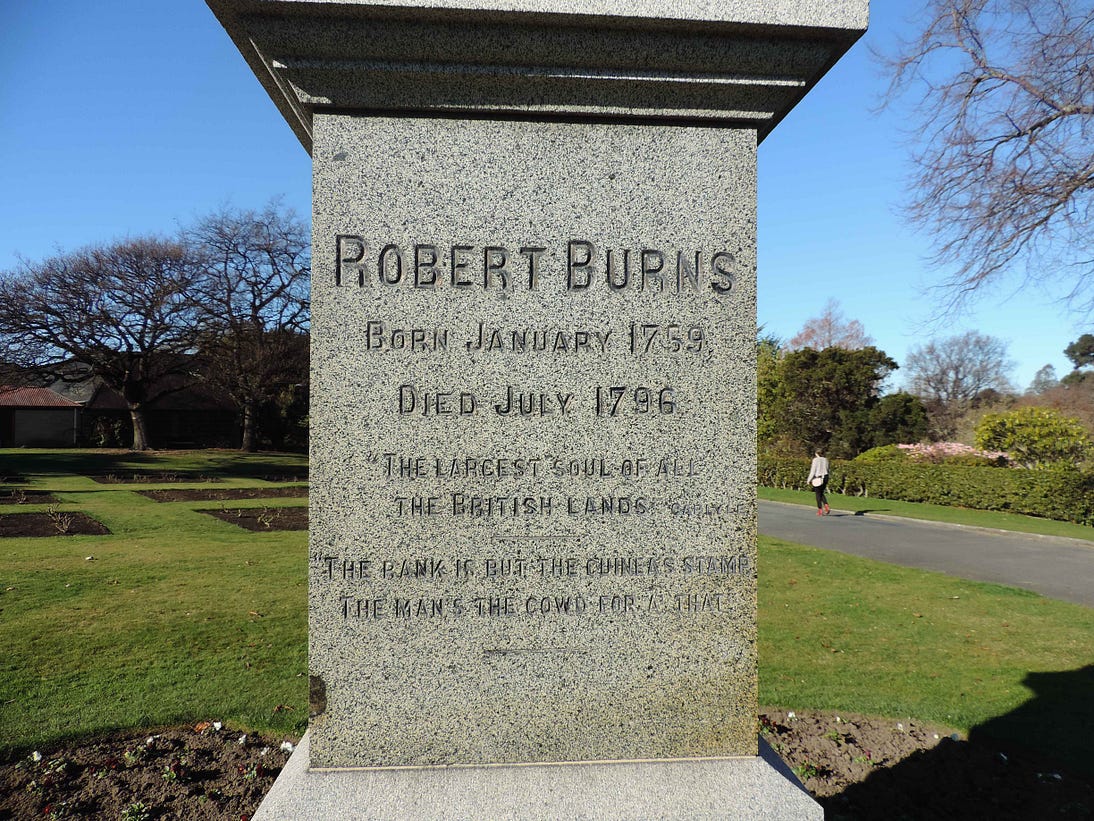

The Botanic Gardens contain a statue of the radical poet Robert Burns, to go with the one in Auckland and the one in Dunedin, not to mention the one in Hokitika and Dunedin’s former Robert Burns Hotel. Burns was, clearly, a rock star to the nation’s early colonists.

All this can be seen in a town that still has a population of less than thirty thousand in its built-up area. The attractiveness and community spirit of these smaller towns and cities is a real reproach to Auckland, pop. 1.7 million. In principle, Auckland ought to be dozens of times as amazing as Timaru. But of course, it is not.

Just before Timaru, there is a road leading to Jacks Point, where there is a further coastal clifftop walkway leading to the Jacks Point Lighthouse.

The name Jacks Point commemorates the famous Ngāi Tahu chief Hone Tūhawaiki, a contemporary of Edward Shortland and Bishop Selwyn who was nicknamed ‘Bloody Jack’ by some of the early settlers.

There is a Māori-language monument on the local road to Jacks Point, also known as Tūhawaiki Point, which reads ‘Tuhawaiki he tohu Maumahara tenei mo Tuhawaiki kura rau i toremi ai ki kone i te tau 1844’. These words mean that it was erected in remembrance of the fact that Tūhawaiki was drowned near this spot in 1844.

The drowning of Tūhawaiki was deemed especially unfortunate by many, since Tūhawaiki, who seemed at home in both worlds, had become an important go-between among the South Island Māori and the settlers who were just then starting to flood into the island in numbers, founding Dunedin in 1848 and Christchurch in 1850.

Here is a view from the start of the track that leads to the Jacks Point Lighthouse. Timaru, and the mountains behind it, are in the background.

The track to the lighthouse also joins up to Timaru’s urban waterfront track, the Hectors’ Coastal Track. This is a great trail on which to go for a long ramble, all the more because it goes past Caroline Bay. So, you can walk the whole thing from the Jacks Point Lighthouse to the Timaru waterfront.

In this region, the state highway is called the Strawberry Trail; which sounds like a curious name for a main road and reflects the fact that strawberries are grown in the region. It was probably more of a trail 100 years ago.

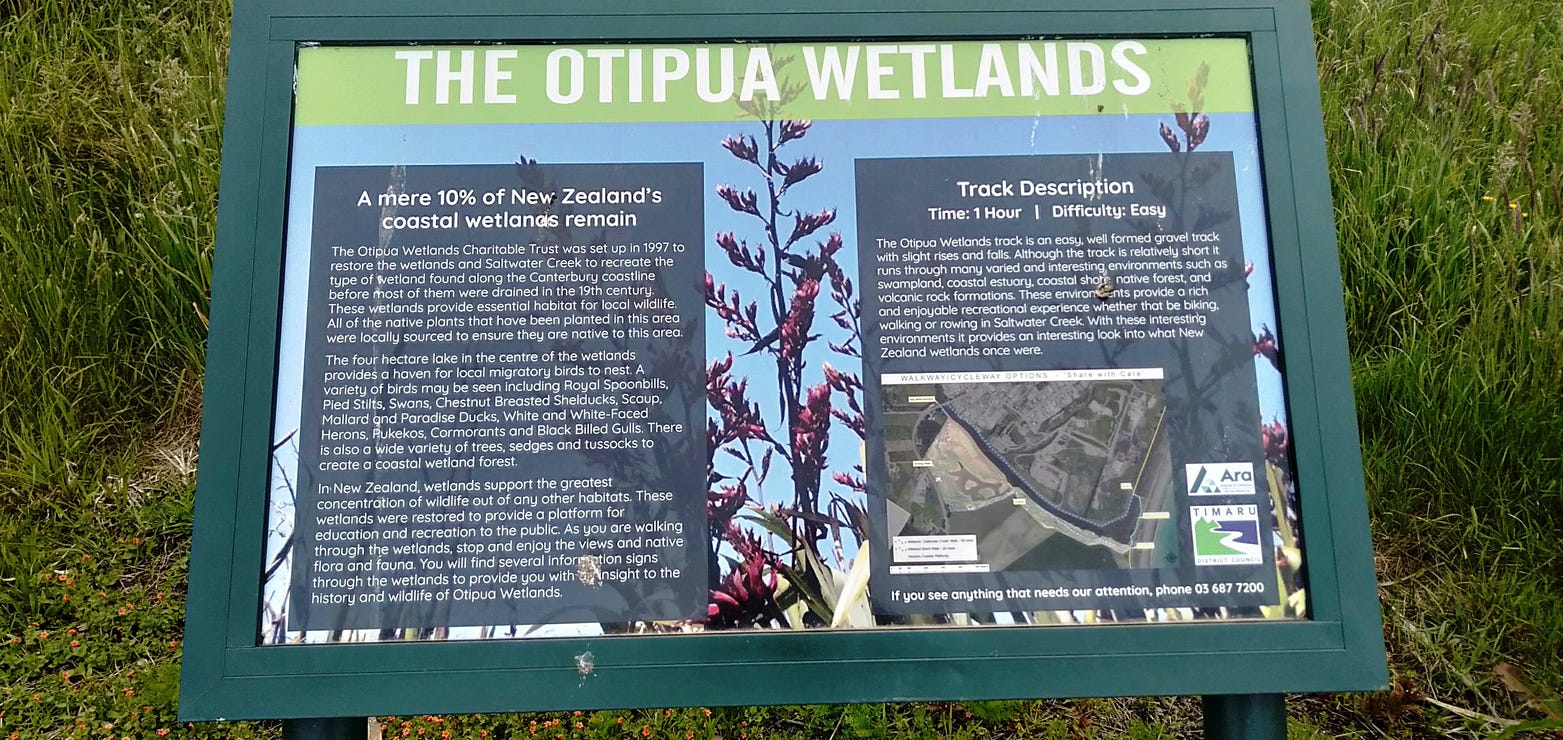

Toward the southern end of the Hectors’ Coastal Track, on Saltwater Creek, there is the Otipua Wetland, or Wetlands: sixty to seventy hectares, or a bit less than two hundred acres, of marshy habitat that has been under restoration by an army of volunteers for more than twenty years.

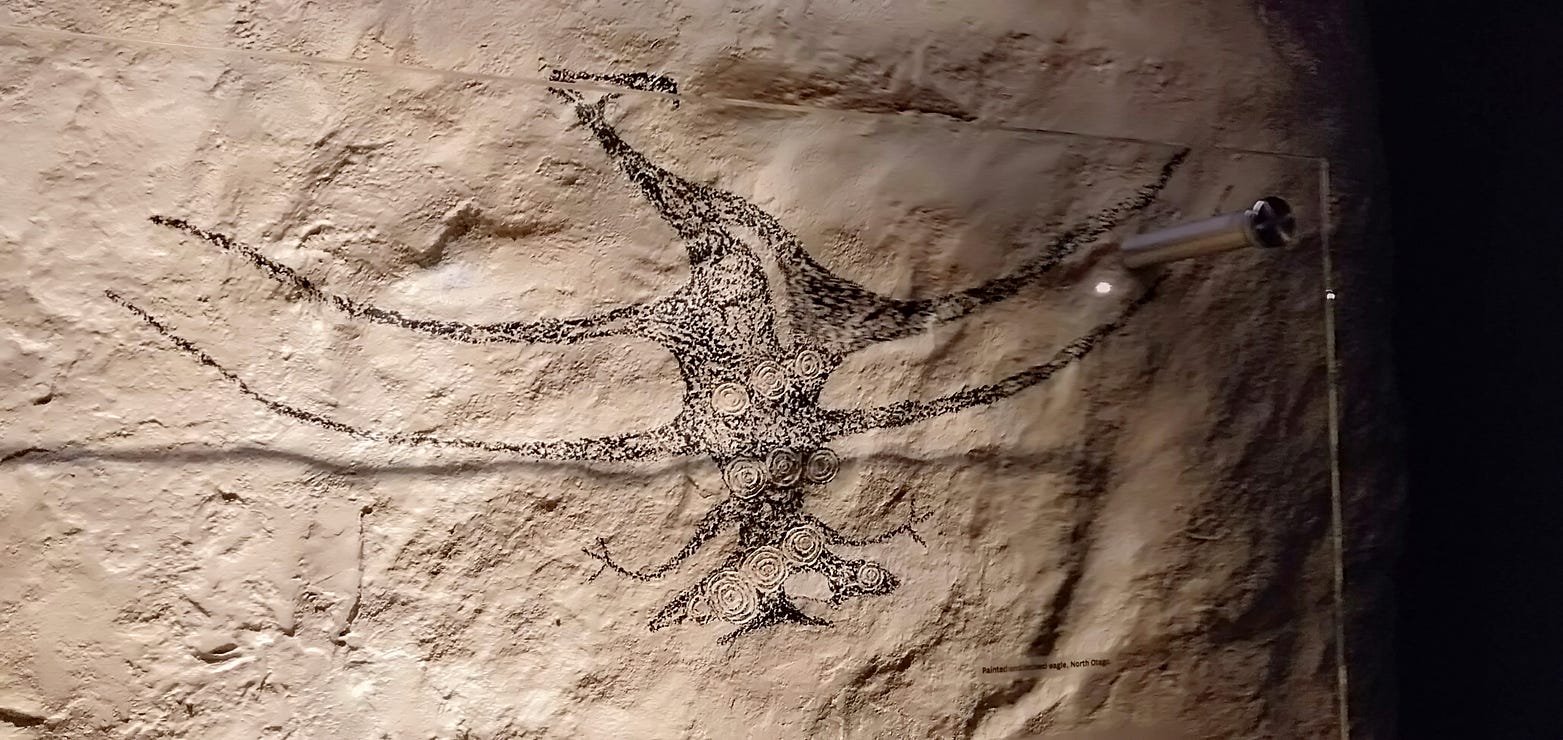

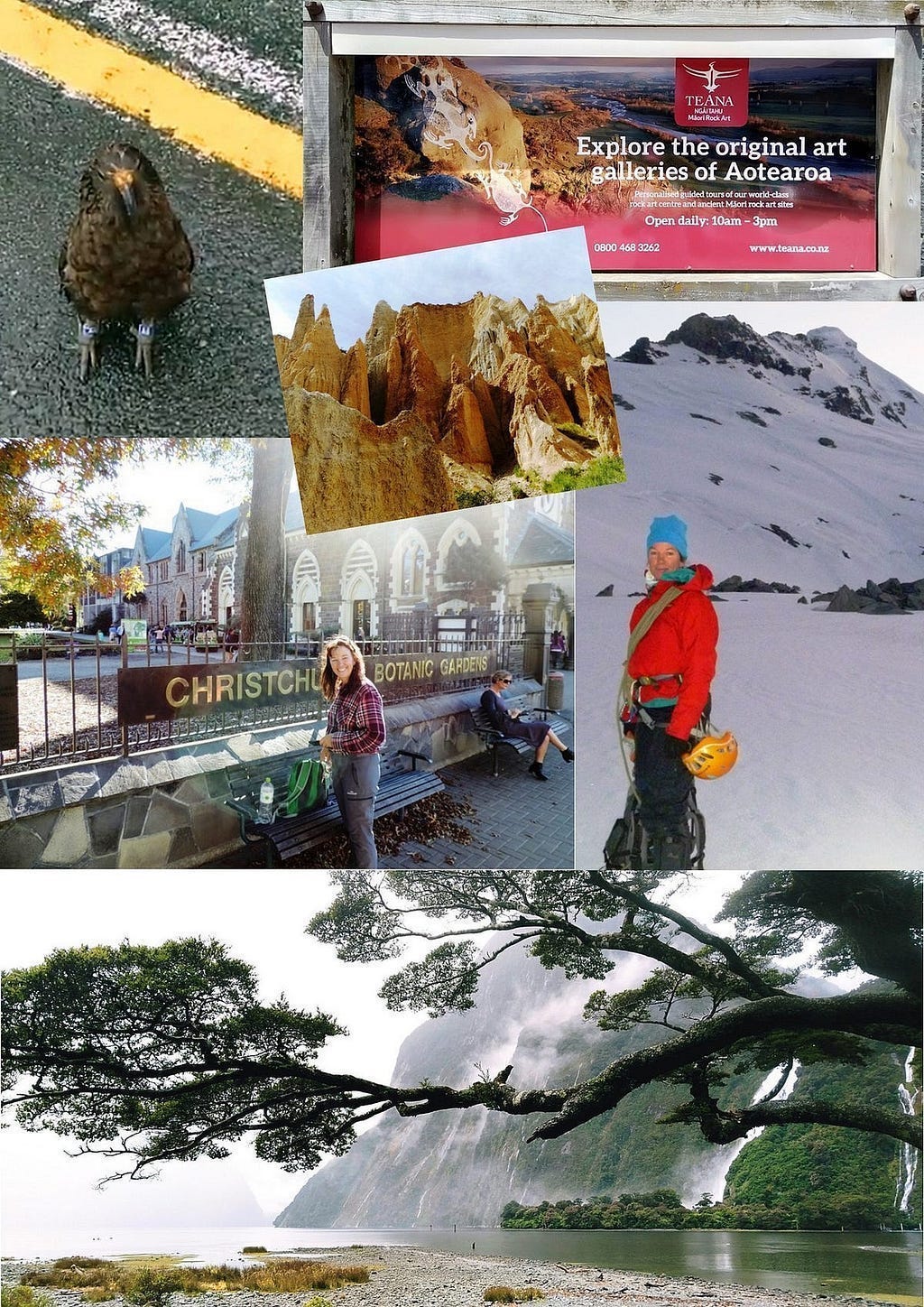

Inside the iSite, you can visit the amazing Te Ana Rock Art Centre, run by the biggest South Island iwi, Ngāi Tahu. Te Ana means ‘The Cave’. It displays rock art done by some of the earliest Māori to settle in the region, basically the local equivalent of European ice-age cave-paintings or Aboriginal rock art in Australia. Such ‘primitive’ art is often amazingly polished and dynamic, as in this European museum replica of French cave-paintings of lions . . .

. . . and the New Zealand version is no exception. At Te Ana, the local Māori seem to have anticipated Pablo Picasso. As do the Chauvet Cave paintings, come to think of it.

Te Ana is conveniently located in the iSite. However, Te Ana also runs guided tours into the countryside, to investigate the actual honest-to-goodness caves.

This is what I mean about Picasso:

Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to get a sharper photo! To make up for it, here’s a video of a projected display showing many of the same designs.

Māori rock art has sometimes appeared on New Zealand postage stamps. There are some images of a 2012 series, here.

Many of the rock drawings at Te Ana are a bit different in appearance to what most people would think of as traditional Māori art, works such as this, which scholars describe as being in ‘classic’ style:

The differences arise partly because the rock art at Te Ana is a few hundred years older than the ‘classic’ style. Its origins and significance are also much more obscure.

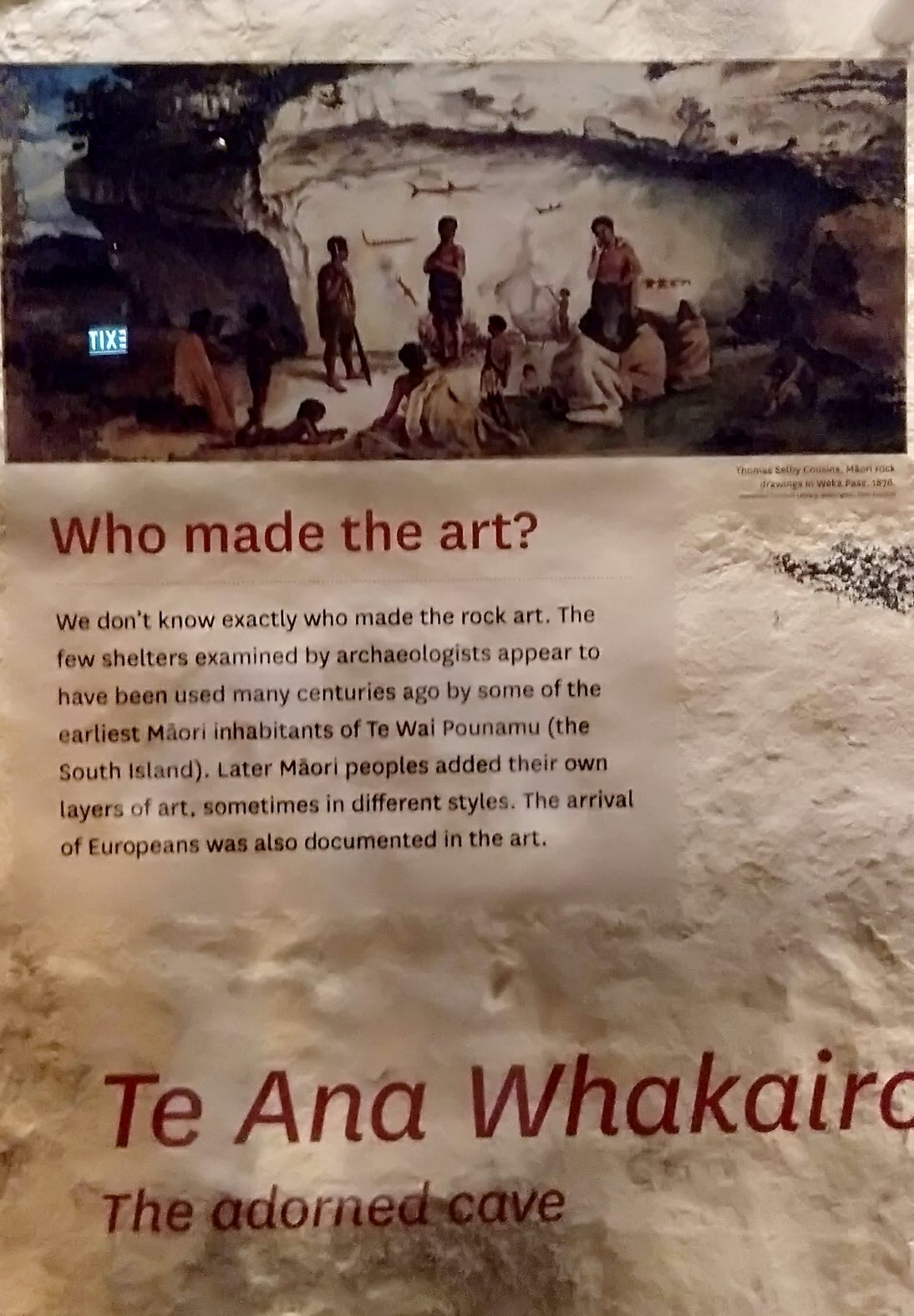

A lot of classic Māori art, like the carving described just above, has a detailed provenance. On the other hand, as the first of the following Te Ana displays says, “We don’t know exactly who made the rock art.”

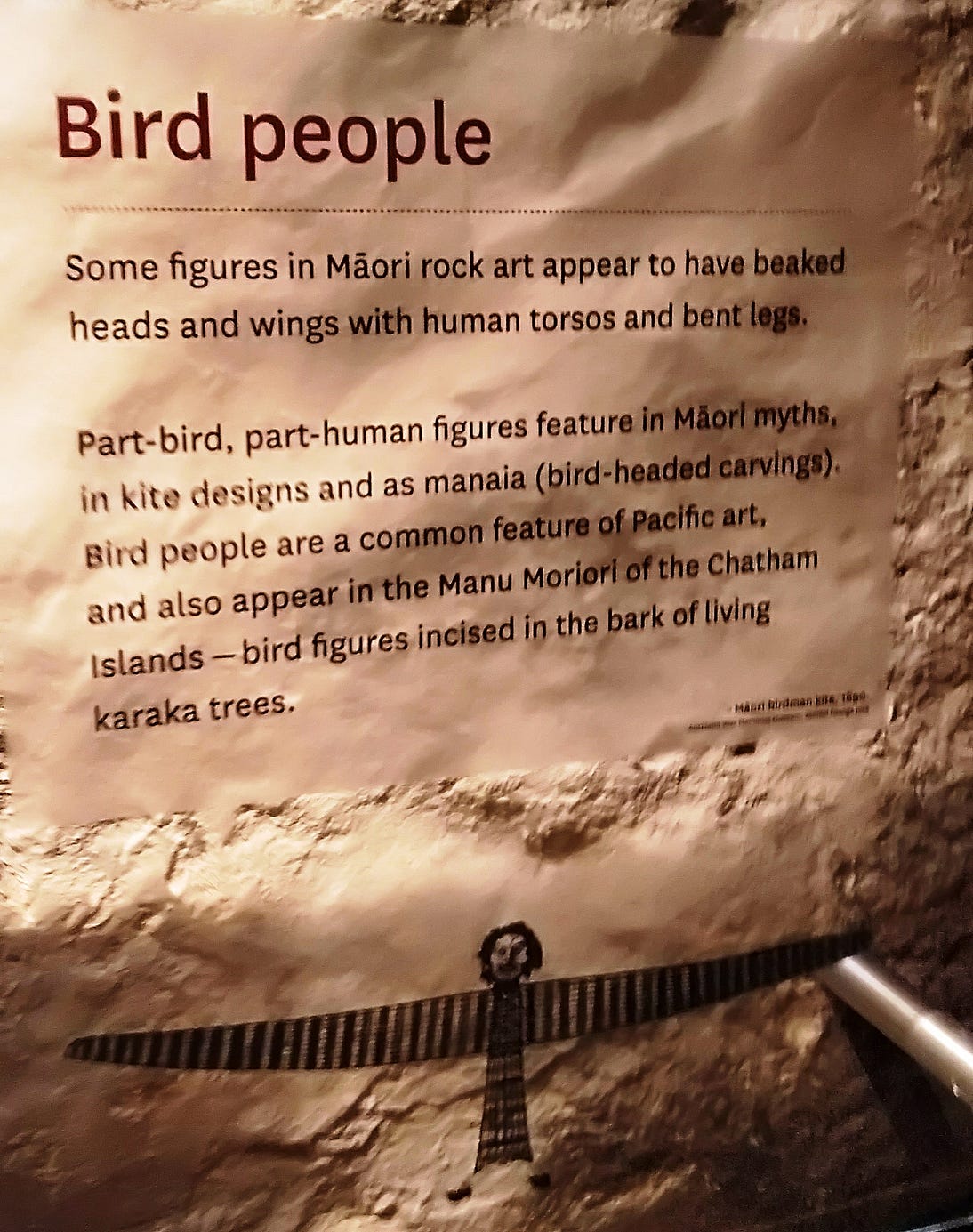

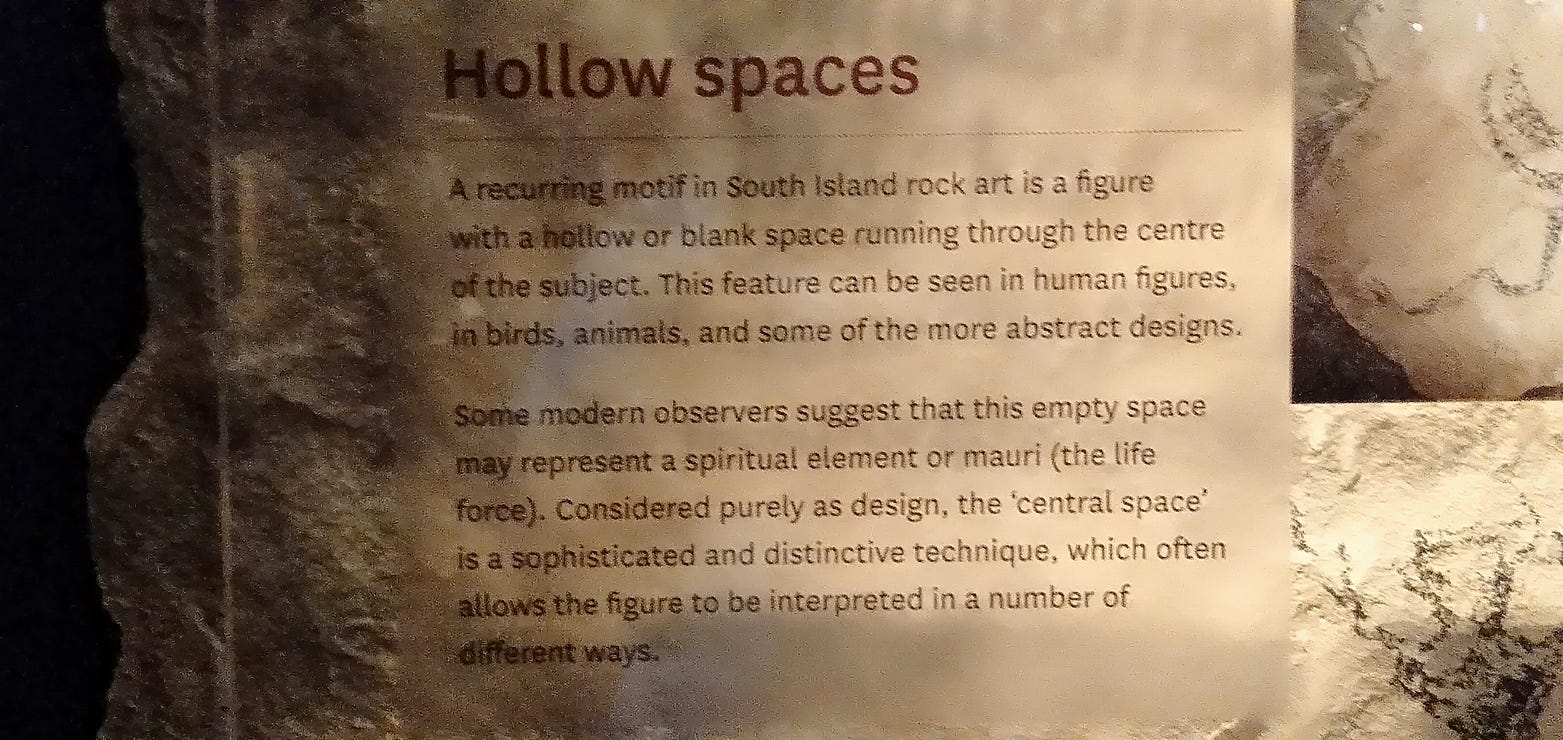

Te Ana also has further information about the distinctive features of the early rock art.

Here is a short video of a karakia, or incantation, at Te Ana.

Ideally, you should spend at least a day and a night in Timaru, which has an affordable and fairly central Top 10 Holiday Park, among other places to stay.

There are plenty of other things to see in the district, such as the Pleasant Point Railway at Pleasant Point, just out of town on the road to Fairlie.

For more tourist information, readers should consult WuHoo Timaru, wuhootimaru.co.nz: the name of which inspired the title of this post!

If you liked this post, check out my book about the South Island! It’s available for purchase from this website, a-maverick.com.

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive free giveaways!