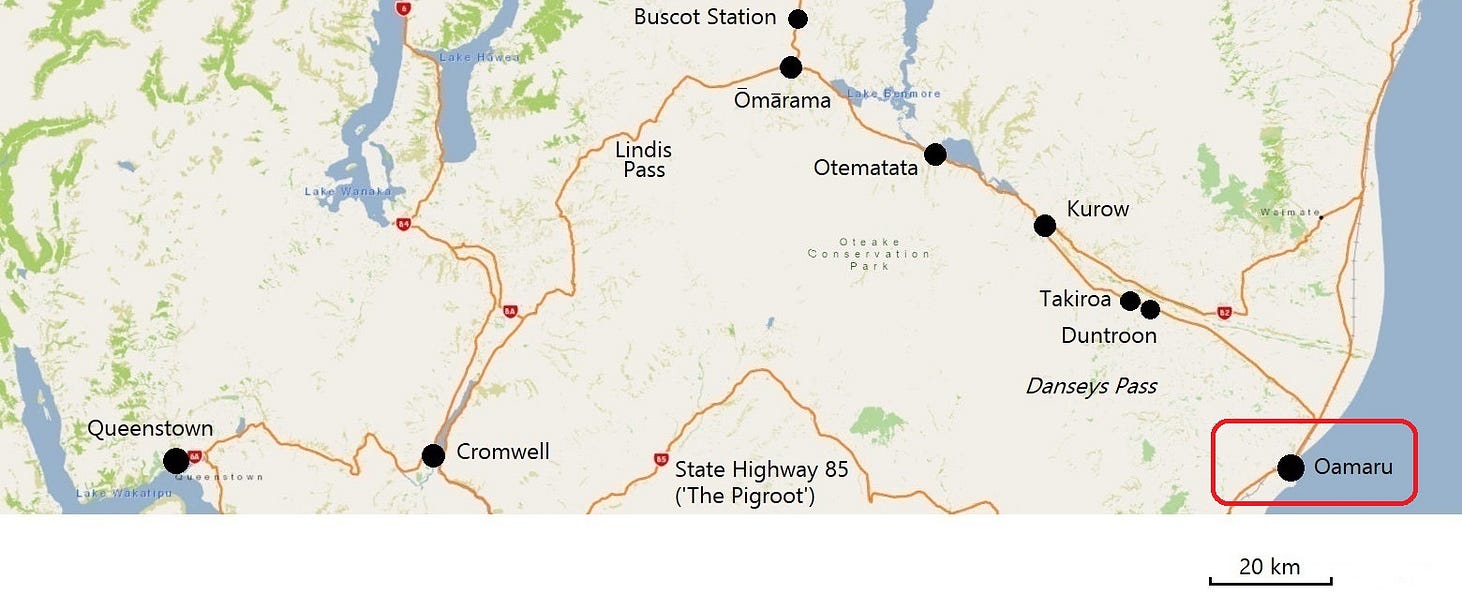

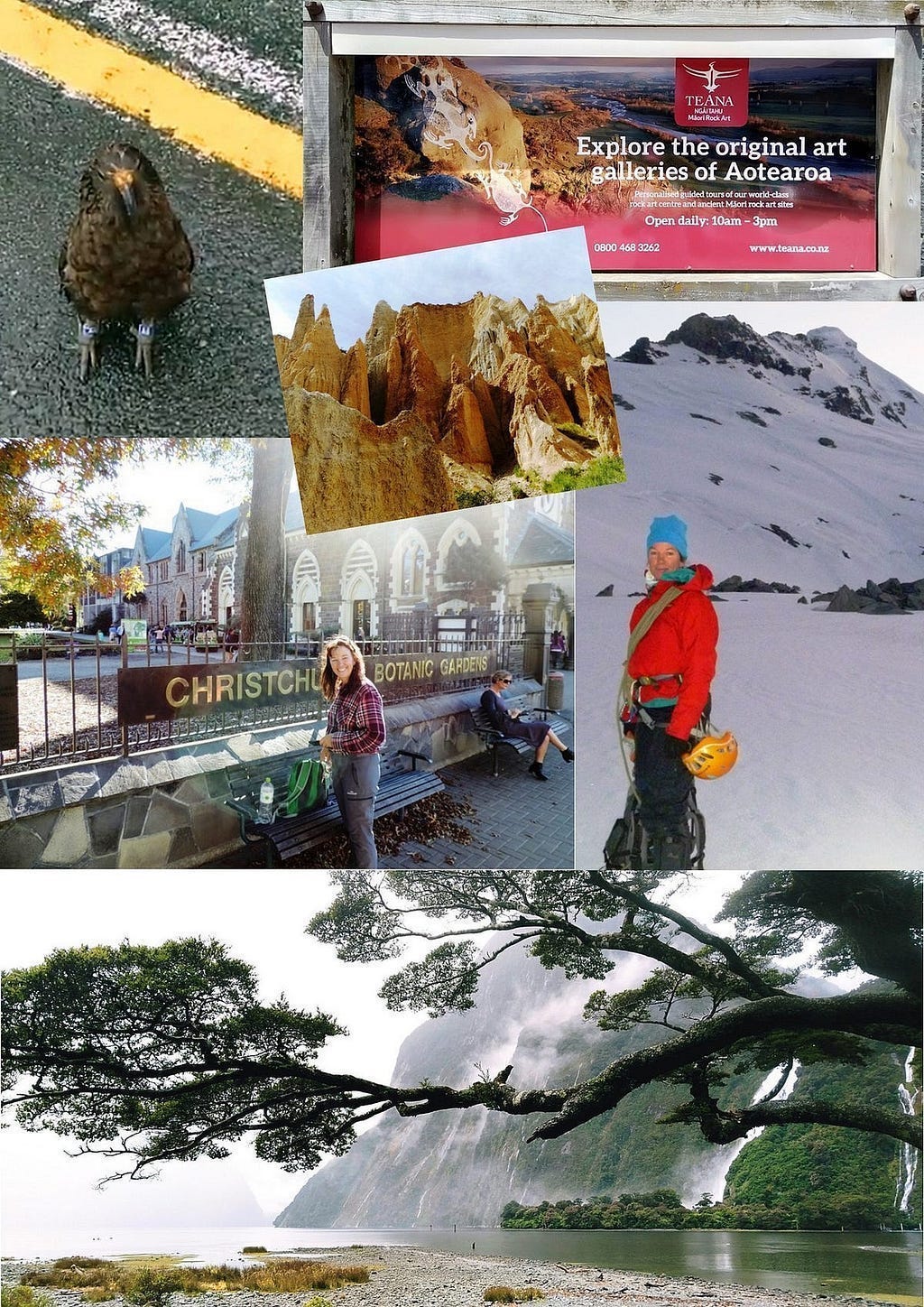

OAMARU is a town of fourteen thousand on the Pacific coast of the South Island of New Zealand. Nicknamed the ‘Whitestone City,’ Oamaru is famous for Victorian architecture made from local white limestone, also known as Oamaru stone.

The main street of Oamaru is called Thames Street.

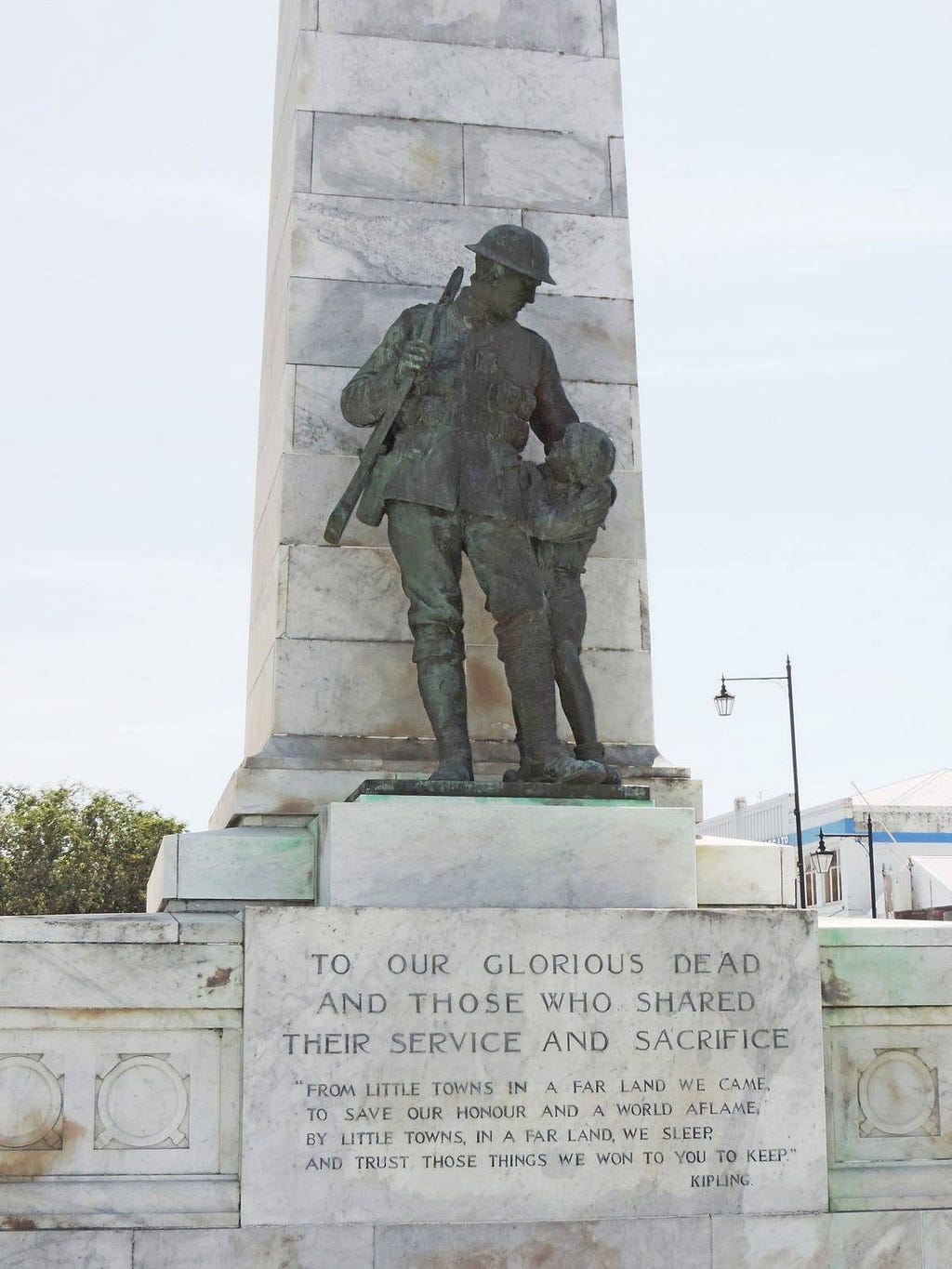

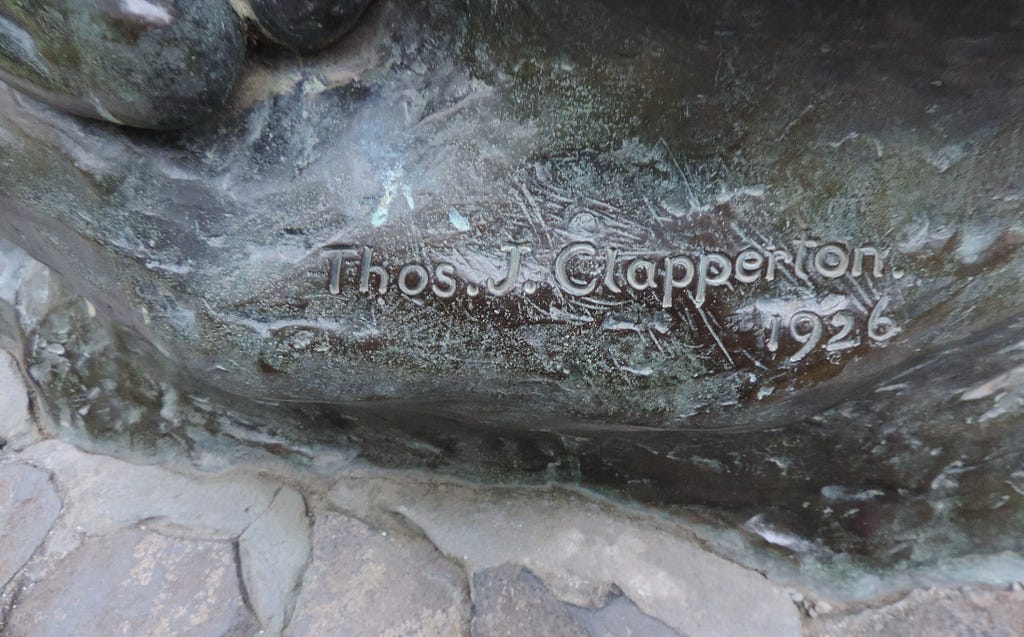

The Cenotaph, in the middle of Thames Street, has a statue by the renowned Scottish sculptor Thomas J. Clapperton on its southern side.

Clapperton sculpted the effigy of Robert the Bruce that guards one side of the main entrance to Edinburgh Castle, opposite Alexander Carrick’s William Wallace. In the following photo, Clapperton’s Robert the Bruce is on the left.

So as you can see, Oamaru has quite a bit of class and connection for a town of only 14,000. It even has an Opera House!

In other South Island towns and cities, Oamaru stone is used for decorative features. In Oamaru, the white buildings look fantastic under nighttime illumination.

Here’s a map of the town that describes its many sights, including 25 numbered historic buildings, a blue penguin (kororā) colony and a yellow-eyed penguin (hoiho) colony.

Plus, a lookout point over Friendly Bay.

The Port of Oamaru was closed to most forms of shipping in 1974, though it remains open to recreational sailors and a local fishing fleet, which keeps the town well stocked with fresh fish. I enjoyed a lovely thick and creamy chowder in one of the local cafes, twice as big as I had expected! So that is another reason to visit the town.

The origin of Oamaru’s name is uncertain, as is the question of whether there should be a tohutō, or macron over the initial O. If spelt Ōamaru, with a macron, it means ‘place of Maru’: a semi-mythological folk-hero to whom the name of Timaru, further up the coast, may also refer. Without a macron, it means Oha-a-Maru, also meaning the place of Maru.

Both spellings can also mean place of sheltered fire, or sheltered place, since maru is also the word for shelter.

From what I have seen, spelling Oamaru without the tohutō is probably more strictly correct and is the form I am following here, but both variants are in use.

If the word Oamaru does refer to shelter, it no doubt refers more specifically to the fact that the town’s site is sheltered from southerly blasts by the cape known today as Cape Wanbrow.

Cape Wanbrow gives Oamaru a favourable microclimate. Whence also, no doubt, the name of Friendly Bay.

There were several Māori kāinga (settlements) and kāinga mahinga kai (food-gathering places) in and around the future town of Oamaru before the area was settled by Europeans in the 1850s.

The expansion of the European town and construction of a port and concrete breakwater from the 1860s onward appears to have ruined the site as a traditional seafood gathering area, with the result that local Māori either moved away or were assimilated into the growing town. These were common outcomes in the South Island, where Māori were fewer in number in the North Island and in a weaker position to resist colonisation as a result.

Here’s a sign pointing to Ōamaru Penguins, spelt with a tohutō, where you can view blue or kororā penguins after sunset in the wild. On the map above, this is shown as the ‘Blue Penguin Visitor Centre.’

I also saw a huge mass of cormorant-like birds perched on an old wharf.

Here’s a video I made about the wharf birds and the penguins!

The blue, or little blue penguins, also known in Australia as little penguins and in Māori as kororā, are the smallest variety of penguin. They nest around the old wharves. These penguins don’t breed in great rookeries like most other sorts of penguins but secretively, two-by-two, in holes in the rocks. The rock rubble under a wharf is perfect for them.

When I was on one of the wharves, I saw a man, a conservation volunteer, saving a little blue penguin that had got lost. Maybe it was a baby one, as it didn’t seem very big even by little penguin standards.

The number of little blue penguins has been going up in Oamaru, from 33 breeding pairs some years ago to 260 now.

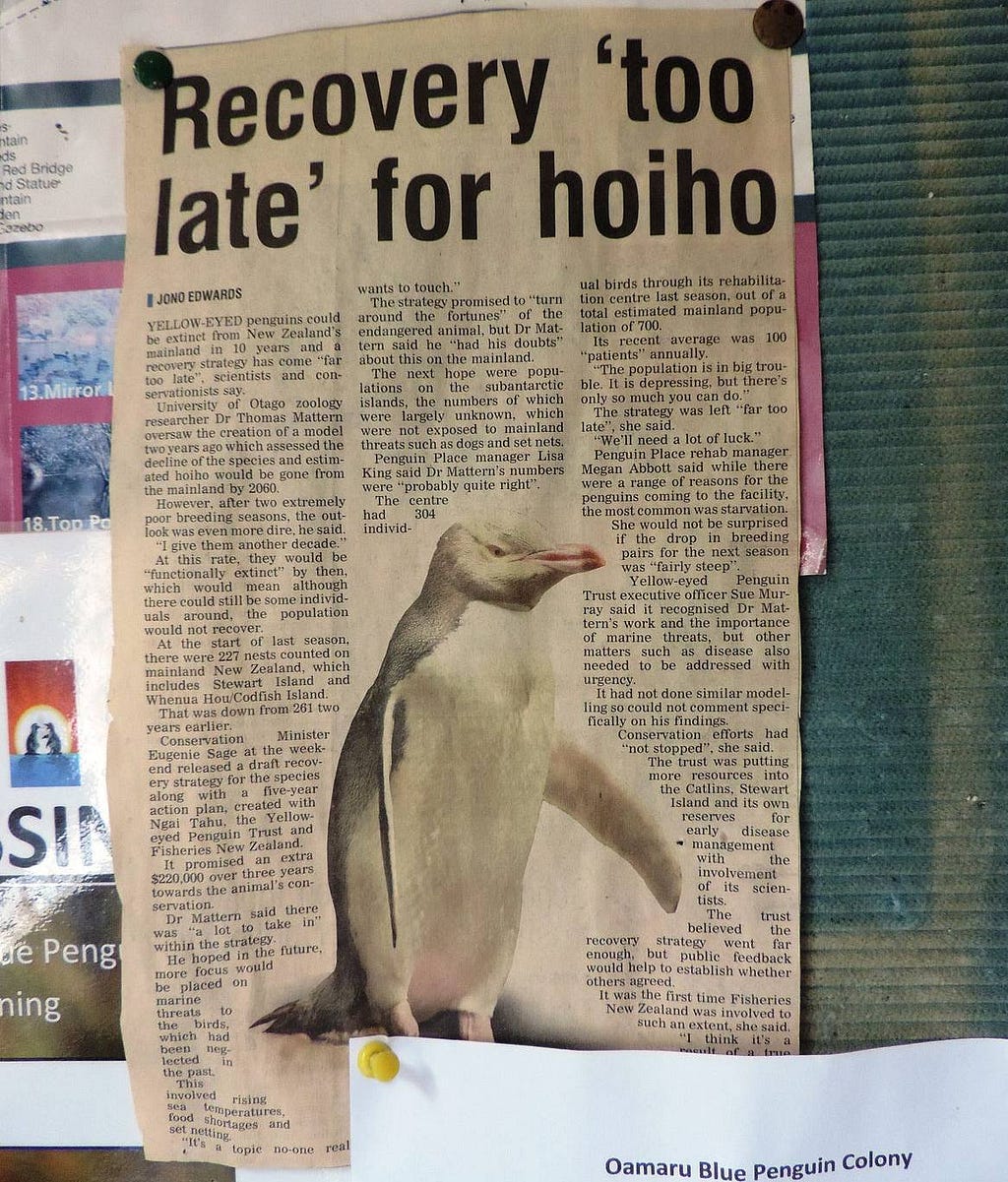

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for the other species that nests in the area, known as the yellow-eyed penguin in English, or hoiho in Māori, a name that means ‘noise shouter.’ The hoiho only breeds on New Zealand coasts; so, it features on the New Zealand five- dollar note as a native bird.

Hoiho are bigger than the little blues, but also nest secretively. Their preferred nesting place is the underbrush of coastal forests. Indeed, Oamaru’s hoiho colony is at a spot called Bushy Bay.

There are also seals at Bushy Bay: snoozing females and males that rear up if anyone gets too close.

Hoiho have a piercing cry, so that members of the species can find each other among the twigs. They’re now an endangered species; a combination of factors such as the clearing of coastal forest and set net fishing seems to have driven a relentless population decline.

Here’s a 2019 article that I saw pinned up when I was staying in Oamaru at the time: you can read the whole story online here. It predicts the possible extinction of the hoiho on mainland New Zealand in ten years’ time from the date of publication, or in other words, by the end of 2029.

Unfortunately, we’re well along that 10 year timeline. Indeed, its numbers have fallen from 739 nests on the South Island and Rakiura / Stewart Island in 2008 to just 115 nests currently, down 20% from 143 nests this time last year.

The government has mandated an emergency three-month set net fishing ban around the Otago Peninsula, though if officialdom was already being accused of being a day late and a dollar short in 2019, that accusation seems all the more pressing now.

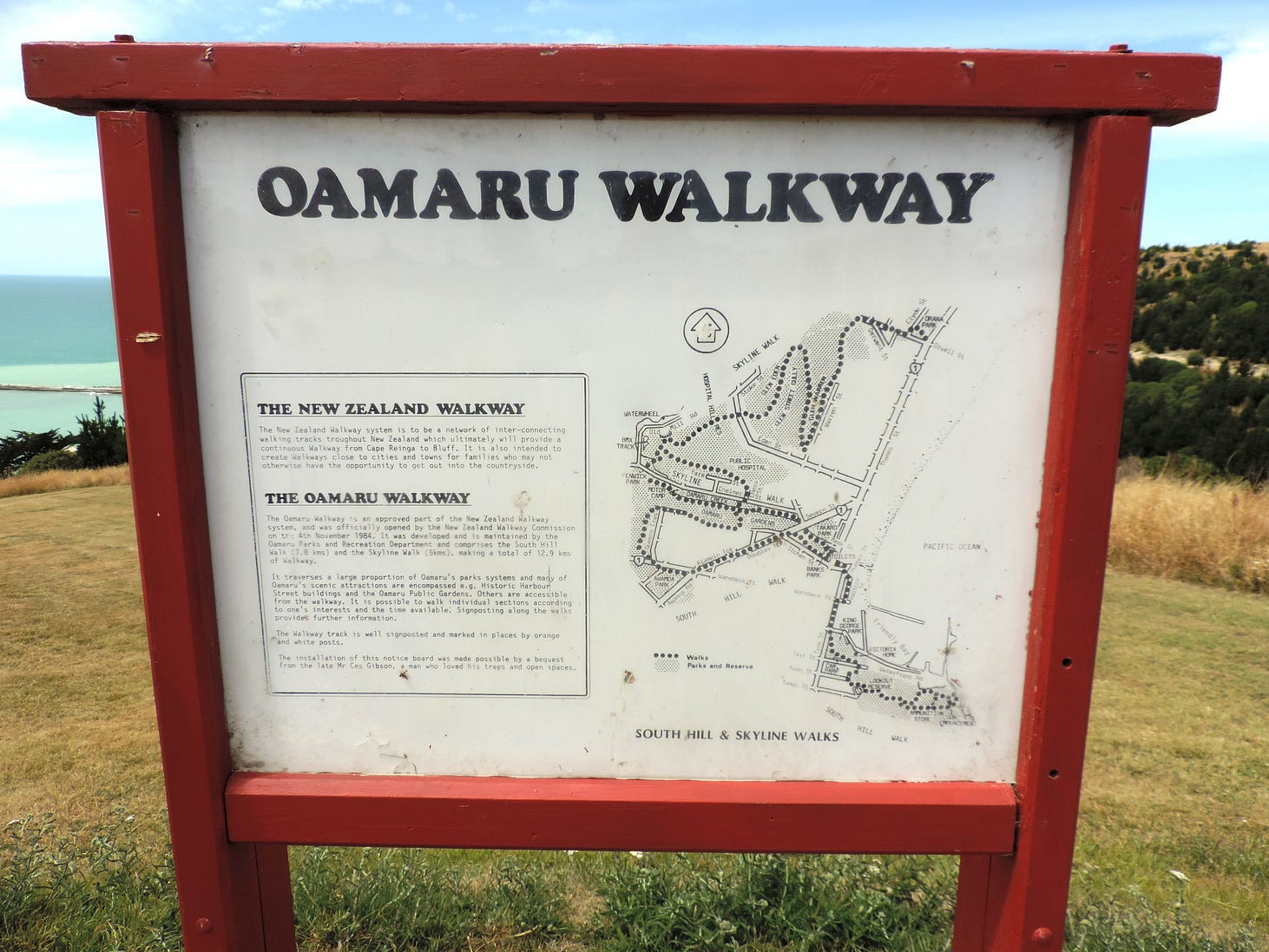

In the map above, you can see several walking trails.

Some of them wind through the formal Oamaru Public Gardens.

Incidentally, Oamaru boasts not one Clapperton statue, but two. The other one is in a section of the Oamaru Public Gardens called the Wonderland Garden. It is called the Wonderland Statue, 100 years old this year.

Here’s another statue in the Oamaru Public Gardens: more recent, I think, and even more whimsical!

Formal gardens lead, by way of the Oamaru Walkway, to a lookout point from which you can gaze down onto the town.

Another walking track runs along Cape Wanbrow to a World War II gun emplacement, on the Wanbrow Reserve.

There’s also a heritage trail dedicated to landmarks in the life and stories of one of New Zealand’s most famous writers, a woman named Janet Frame, who wrote novels and short stories set in town.

The most famous (true) story about Janet Frame is that she was scheduled for a lobotomy at the Seacliff asylum outside of Dunedin in the hope that this would cure her of highly-strung eccentricities — it didn’t pay to be either too eccentric or too highly strung in 1950s New Zealand — but that the operation was cancelled after one of her collections of short stories won a literary prize! Ms Frame’s family home, at 56 Eden Street, is now a literary shrine.

And there is also a Harbourside Walkway.

To round off, an electrical junction box has been painted up to reflect Oamaru’s literary claims to fame, as well as penguin viewing. There’s a little joke woven in.

Penguin — geddit?

Next week, I will be exploring the now-famous Victorian heritage area around the former port, and taking a trip to see the bizarre Moeraki Boulders 30 km to the south of Oamaru.

If you liked this post, check out my book about the South Island! It’s available for purchase from this website, a-maverick.com.

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive free giveaways!