FOLLOWING my two days in Potsdam, covered in this post, this one, and this one, I caught the suburban S-Bahn train from the Potsdam Hauptbahnhof, or main station.

The train mostly passed through the former West Berlin. There were lots of views of historic buildings, such as the Theater des Westens, or Theatre of the West.

I arrived at the Berlin Hauptbahnhof, which had more platforms than I had ever seen in one place and was somewhat confusing for a first-timer!

Finally, I made it to the historic district, dominated by the colossal Berlin Cathedral.

The Berlin Cathedral is on an island in the middle of the River Spree, the main river running through Berlin. This island is called Museumsinsel, or Museum Island, as it has several famous museums on it as well. If I had been in Berlin for a bit longer, I would have definitely visited these museums, as some of their exhibits, like the Ishtar Gate, the most important of the eight gates in the city walls of ancient Babylon in the 500s BCE, are just totally world-famous.

The Ishtar gate was dug up in a damaged state and smuggled out, brick by brick, from what is now Iraq, then part of the Turkish Ottoman Empire, by German archaeologists before the First World War.

The Ishtar Gate’s restoration, re-erection, and retention in Berlin has since become controversial, in the way that now dogs many European museums and their collections. Iraq would like to have it back. On the other hand, if it had remained in Iraq, it might have been destroyed or looted by some other thief of antiquities by now (although, then again, it was damaged all over again toward the end of World War II in Berlin, so there are swings and roundabouts in that regard).

In front of the Berlin Cathedral you can see a park called the Berlin Lustgarten.

The Lustgarten backs onto the Altes Museum, or Old Museum, the oldest of the museums on the island. The Latin inscription says that it was established under Frederick William III in 1828.

Which is actually a bit late in the historical day by European standards, at least for something that claims to be the oldest museum on the island. The New Town in Edinburgh is older than that, by some fifty years.

We tend to think of European cities as being really old, but the reality is that much of Berlin, even in its most cultural districts, is not really much older than Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch, or Dunedin.

The Pergamon Museum, the most famous museum on Museum Island, the one that contains the Ishtar Gate, was actually opened a few months after the Auckland War Memorial Museum. Which, by the same token, wouldn’t look the least bit out of place on Museum Island.

As for the Berlin Cathedral, it was built between 1894 and 1905, which makes it quite a bit younger than many of the churches in Christchurch and Dunedin, indeed younger, if only once again by a few months, than the lately demolished Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament in Christchurch, another Kiwi building that would not have looked out of place in this part of Berlin.

Another way of looking at this is that we don’t have to put up with crappy cities in New Zealand.

We could have cities that look every bit as good as the ‘historic’ parts of European cities, large parts of which were indeed built at about the same time as Christchurch and Dunedin. (And we could have tramways and bikeable streets and all the rest, too.)

This is not to say that there are not a few buildings that date back to the Middle Ages in Berlin: but only a very few. The Marienkirche, from the 1200s, but of which perhaps the most original bit now is the spire, is one of them.

Facing the Berlin Cathedral, there was an embankment of the River Spree, which also contained the DDR Museum, DDR being short for Deutsche Demokratische Republik, or German Democratic Republic, the official name of the former East Germany. I will talk about my visit to the DDR Museum next week.)

River boats, and a walk toward the Cathedral and the DDR Museum

The embankment had bronze statues in a sitting position, to encourage real people to sit beside them, I suppose.

A little further along toward the centre of town, just across the Schlossbrücke or Palace Bridge from Museum Island, is the Zeughaus, or armory, the oldest of several notable heritage buildings on Unter den Linden, a grand avenue along which I was then to walk, until I got to the Brandenburg Gate.

Unter den Linden is the premier avenue in Berlin. Its name means ‘Under the Limes,’ a leafy, deciduous, European tree sometimes called linden in English as well.

European limes, or linden, were for a long time the only type of street trees along Unter den Linden, whence the name.

(The Wellington suburb of Linden is also ultimately named after the European lime, or linden, which sadly does not produce the kind of lime that you squeeze into a drink; that comes from a different sort of tree!)

The Zeughaus was completed in 1706 under Frederick I, the first Prussian king.

As befits that time in history, the decoration of the Zeughaus is totally baroque, in ways that would not look out of place in a Spanish-speaking country, such as Mexico for instance.

These days, the Zeughaus is part of the Deutsches Historisches Museum, or German Historical Museum. The next photo shows the Zeughaus flying the flag of the museum, amid more baroque figures on top and still more statues, in the same style, on the Palace Bridge.

The feeling that this all looks a bit Mexican is reinforced by the motif of an eagle assaulting a snake.

Many cultures, from the Greeks to the Aztecs, have a legend about a fight between an eagle and a snake. I suspect the Berlin design draws on the Greek version rather than the Mexican one, if only because Greece is a lot closer and, secondly, because there is no cactus underneath.

However, the Spanish look soon went out of style in Berlin, and later buildings were done in the neoclassical style — the sort that looks like a homage to ancient Greece or Rome—which was in vogue from about the time of the American Revolution to the mid-1800s.

Much as with Washington DC, neoclassicism is the style for which Berlin is most famous; the origin of its nickname ‘Athens on the Spree.’ Examples include the Alte Nationalgalerie, or Old National Gallery:

And the small but perfectly formed Neue Wache, or New Watch, i.e., guardhouse, just a little further along on Unter den Linden:

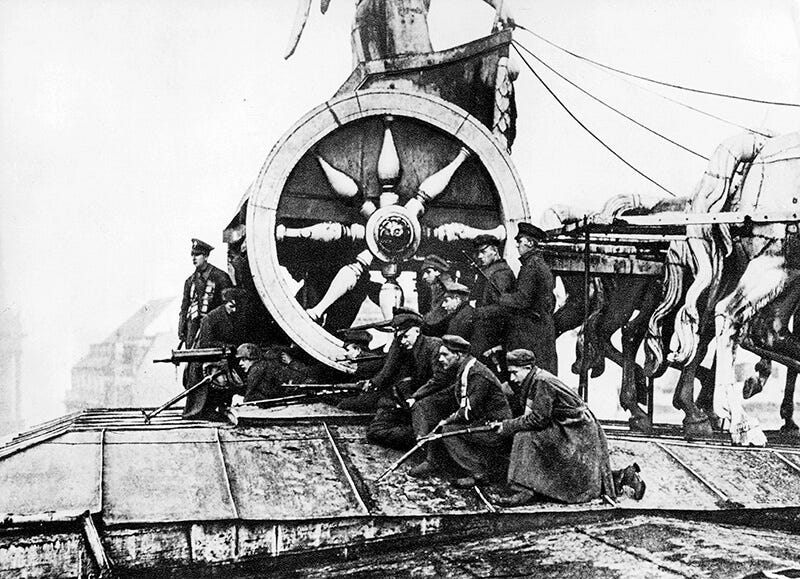

And, of course, the Brandenburg Gate, on Pariser Platz at the very far end of Unter den Linden, just short of where East Berlin became West Berlin in Cold War days. The next photo shows the gate and the two small covered colonnades known as stoas beside it in an almost side-on view, with the famous bronze statue of Victoria, the Roman goddess of victory (over Napoleon, in this case) and four horses on top, the so-called Quadriga, facing eastward.

Like many of the more delicate cultural artifacts in downtown Berlin, the Quadriga is a bit like one’s grandfather’s axe, having been heavily damaged and restored over the years in assorted wars and revolutions, hopefully with none more to follow.

The only surviving original piece of the Quadriga is a horse’s head, kept in the Humboldt Forum, across Unter den Linden from the Lustgarten and the Cathedral.

The Humboldt Forum is a modern museum. named after the scientist and philosopher Wilhelm von Humboldt. It is located in the rebuilt Berlin Palace, of which the original was torn down by the Communists.

The next image shows the original Berlin Palace, with its dome, in the background, while the revolutionaries of the year 1848 wave different versions of their flag, all of them in red, black, and gold (the Prussian flag was black and white, and that of the Prussian-dominated German Empire of 1871 to 1918, red, white, and black). The modern German flag descends from the flags of the 1848 revolution, which fortunately spared the Quadriga that time around.

Further along toward the city centre on the same side of Unter den Linden is Bebelplatz, renamed by the East Germans after August Bebel, a famous socialist of pre-World War One days. Bebelplatz remains an official name to this day, though the plaza used to be known as the Opernplatz because the Deutsche Staatsoper, the German State Opera, is on the plaza, and Opernplatz is what a lot of modern-day Berliners call it in practice

In the following photo of Bebelplatz (or Opernplatz), the Deutsche Staatsoper is to the left, while the building with the distinctive dome is St Hedwig’s Cathedral, built by Frederick II for his newly acquired province of Silesia, a partly Polish territory of which Hedwig was the patron saint, even though Prussia had hitherto been militantly Protestant.

Here are some video pans around the area, with the full explanation of what is shown in the video notes on YouTube. The thumbnail for the video shows Humboldt University, with a statue of Humboldt in front. The Humboldt Mountains, near the Routeburn Track in New Zealand, are named after this same individual.

I carried on down Unter den Linden, spotting tourist buses on several occasions. Note also the number of bikes, again!

There was another statue of Frederick II, massively decorated with images of his contemporaries so that they, too, would not be forgotten.

There was also a souvenir shop, the Ampelmann store, named after the famous East German traffic light figure, the Ampelmännchen, or little traffic lights man (also known as the Ampelmann). The U-Bahn station for Unter den Linden is in front.

And so I got to the Brandenburg Gate and its eastward-facing, tourist-thronged Pariser Platz, flanked by two neoclassical guardhouses on either side of the gate, and with the famous Hotel Adlon, which also features in numerous historical dramas set in Berlin, facing it. The modern-day Adlon, too, is a ‘grandfather’s axe,’ as the hotel was destroyed save for one wing in World War II, and only recently rebuilt.

Here’s a pan around the Pariser Platz:

The Brandenburg Gate is one of the symbols of Berlin, as you can see on the right side of the next photo, where several symbols of Berlin form a heart, meaning ‘We love Berlin.’

There are, indeed, lots of English-language words on signs in Berlin, doubtless aimed at tourists as well as the large number of English-speaking émigrés, fed up with their own countries, who now live in Berlin.

Also on that ‘We Love Berlin’ design is the Siegessäule or Victory Column, well inside the former West Berlin, which celebrates Prussia’s and Germany’s victories over the Danes, the Austrians, and the French in the 1864–1871 Wars of German Unification.

It is possible to climb all the way to the top of the Victory Column for a good view over the city.

The golden goddess on top, officially Victoria but nicknamed Goldelse (‘golden Lizzie’), is on the right side of the collage at the tram stop above, under the bear, the most official symbol of Berlin, which seems to be embracing the TV tower.

Meanwhile, back at the Brandenburg Gate, I photographed somebody else photographing a stage where it looked as though someone was going to rally a protest about Gaza.

The stage was where the Berlin Wall used to be.

And where Ronald Reagan gave his ‘Tear down this wall, Mr Gorbachev’ speech in 1987.

It must be strange to live in a city where so much has changed and where there has been so much history, especially if you are an older person and remember some of it.

Then I wandered over toward the Reichstag building, which is on the territory of the former West Berlin, and now the location of the German Bundestag, or Federal Parliament. The building originally housed the German parliament in the days when it was known as the Reichstag, whence the name of the building.

The words on the pediment, Dem Deutschen Volke, mean to, or for, the German people. I’m not sure what purpose the ugly temporary structures in front serve. The building also has a modern transparent dome on top, designed by Sir Norman Foster, a very eminent architect, to symbolise transparent government; though I am not sure it goes with the rest of the structure.

Eventually, I made it back, on foot, to the Berlin Hauptbahnhof, past a whole lot of people sunning themselves on the banks of the River Spree. You can still see the TV tower in the background!

Part 2 will appear next week.

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive free giveaways!