THIS week, I’m blogging about a completely different topic: the proposal for a new gold mine in North Otago.

It’s a historic area, full of old goldmining ruins, part of which I’ve just lately blogged about in a post called The Romantic Lindis Pass.

From time to time, I’ve made a trip to the Bannockburn Sluicings Historic Reserve, as it isn’t far from Queenstown. Here, the landscape was carved up by water jets directed at a gravel landscape left by ancient rivers, containing flecks and nuggets of gold. It was the same process that formed the lakes at St Bathans, near Cambrian, at the top right of the map above.

Here are a couple of photos I’ve taken in the Bannockburn area, which is the part of Central Otago closest to Queenstown.

On one of my visits, I went for a ramble past the local Bannockburn Domain campground and village onto the Sluicings Track. Here is a video made up of scenes I filmed and photographed that day, plus a couple of collages from still photos that I also took on the same day!

Bannockburn area video, including a slideshow

Check out ‘Bannockburn area’ on the New Zealand Department of Conservation (DOC) website for a list of things to do in and around Bannockburn, including the Bannockburn Sluicings Track.

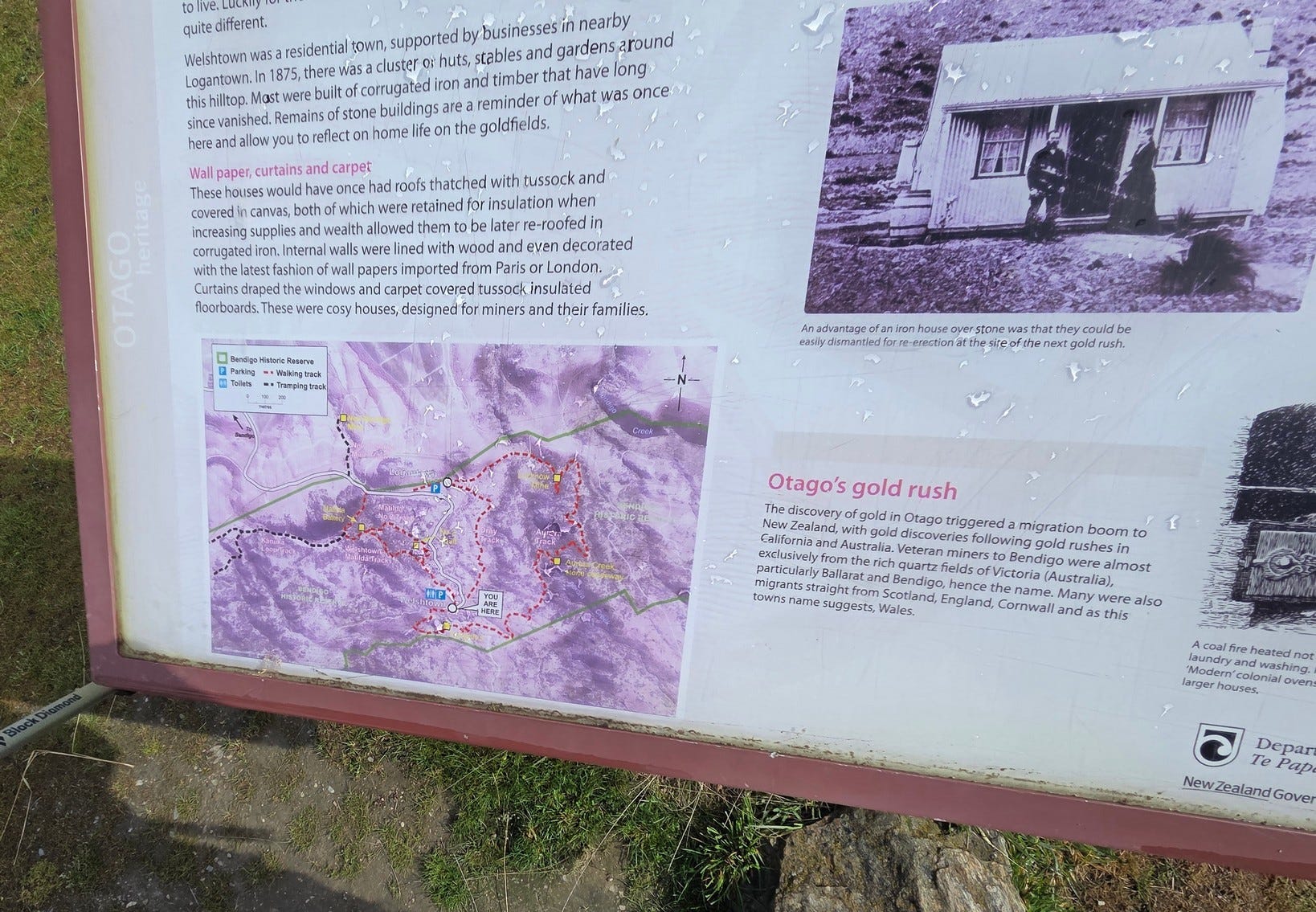

There are more ruins in a place called the Bendigo Scenic and Historic Reserves, or more broadly the Bendigo Goldfields, up in the hills overlooking the Lindis Valley and the headwaters of the Clutha River. There are hiking trails through this area and, nowadays, lots of vineyards.

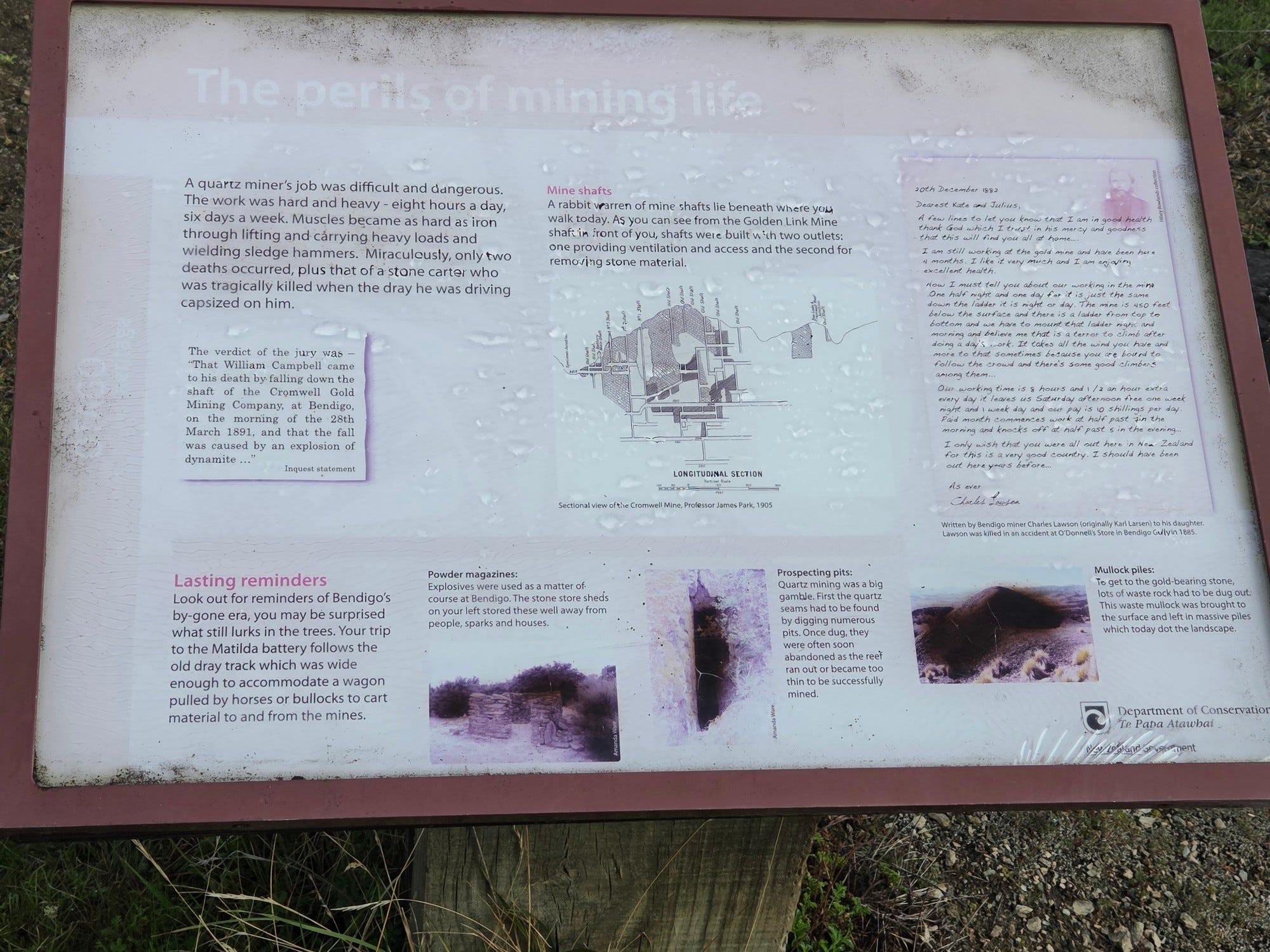

In this area, which is up in the hills and made of firm rock, the gold was extracted from its ore (mostly quartz) by means of stamper batteries, which crushed the rock to powder.

Like Ballarat Street in Queenstown, which is named after the City of Ballarat in the central highlands of the Australian state of Victoria, the Bendigo Goldfields of Central Otago are named after another Australian gold rush boomtown, namely, Bendigo, Victoria.

The next map shows the location of some of the old batteries in the Bendigo Goldfields of Otago.

‘Location map of the Bendigo goldfields region, Otago, New Zealand including the former settlements of Bendigo, Logantown (unofficial) and Welshtown (unofficial). The location of the quartz reefs historically mined and important quartz stamper batteries are included.’ Map by TheKiwiAbroad, 16 July 2023, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The powder was mixed with water, and the gold fell to the bottom. But that didn’t get all the gold.

Toxic chemicals such as mercury and cyanide solutions were also used to extract the gold from particles of rock it was still stuck to.

Though gold is ‘noble,’ meaning that it is inert under normal conditions, it can be dissolved by extra-harsh chemicals.

Metallic mercury, cyanide, and a couple of rare acids can all dissolve gold in a laboratory or workshop.

Gold also dissolves in really hot and highly pressurised geothermal waters underground —a witches’ brew capable of dissolving just about anything, including the rocks themselves — and then precipitates out again as the waters approach the surface and cool down.

That is how gold so often ends up, in nature, as flecks and veins in geothermal rock crystals like quartz, which form when dissolved rocks come back out of solution at about the same time as the gold (if there is any).

For the last hundred years and more, hard-rock mining of gold has involved crushing geothermal rock crystals and dissolving the traces of gold that they contain with chemicals.

One of the stamper batteries has been restored, the Come in Time battery, visible toward the right of the map above.

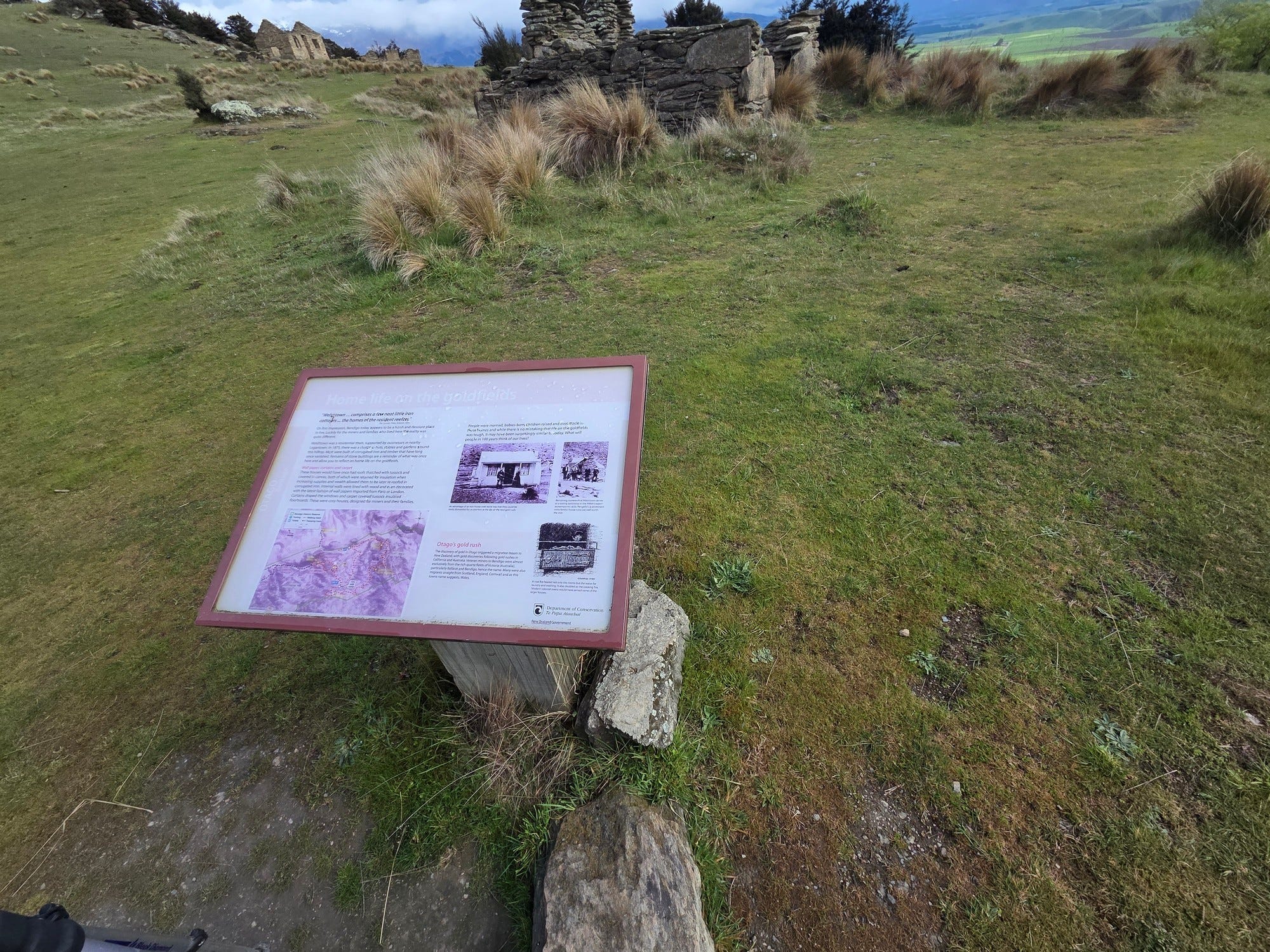

Well, just lately, I managed to visit this wonderful area, starting at the Welshtown car park, from which several tracks led to historic sights, including a restored stamper battery where rocky ore was crushed to release the gold.

Here are some old structures and a dangerous mineshaft with a metal grille on top.

There really are lots of tracks. I did the Kānuka Loop, which takes several hours.

The next couple of photographs show outcrops of potentially gold-bearing quartz, poking through the softer rocks and soil around them.

And a view out over the Lindis Valley, again.

Here’s a short video I made, just panning around.

The atmospheric 1979 TV play Jack Winter’s Dream harks back to those bygone days:

These days, there many wineries in the area, 22 listed on Yellow for the Lindis Valley alone.

Anyhow, the current proposal is for four open-cast pit mines to be dug by a firm called Santana Minerals, with the largest one a bathtub-shaped hole a kilometre long. Once these are fully dug out, underground mining would then take place.

Some fear these highly visible mines may extend into the historic reserve.

In fact, most of Central Otago is covered in prospecting or exploring permits, as there is a widespread belief that modern methods could recover far more gold from Central Otago than the older methods.

Santana Minerals believes its largest pit, named Rise and Shine after an old historic mine in the same area, could win 2.6 million ounces of gold, at an average concentration of 2.5 grams per metric ton of rock mined, or in other words, just 2.5 parts per million by weight.

(Presumably, this refers to the gold seam itself, in which gold is mixed by geological processes into other minerals such as quartz, and not the total of all the rocks of various sorts dug out to get at the gold.)

In the old days, the concentration in the gold seam had to be much higher, 10 to 50 grams per tonne. Modern technologies make lower concentrations economic to mine. And so, all over the world, people are going back to long-abandoned goldfields for another bite at the cherry.

All the same, according to a 9 June 2025 story in the Otago Daily Times, ‘Yes, all that glistens is not always gold,’ Santana, a firm founded in 2013 and headquartered in Brisbane, Australia, haven’t ever operated a goldmine before.

As the modern technology for extracting gold from crushed ore also involves dissolving the gold out of the ore in vats of dilute cyanide solution, there is obviously plenty of potential for things to go wrong.

Not so much in terms of worker safety, perhaps, unless the accident is very bad. But certainly, in terms of various sorts of spills and lingering pollution.

That said, there would be fewer worries if the operators had a lot of experience.

And if the regulators and inspectors of mines were on the ball.

Indeed, the cyanide process is not new, and was in fact pioneered in New Zealand, in the Karangahake Gorge, in the 1890s.

Walking around the old workings in the Karangahake Gorge, you can to this day see patches of ‘blue billy,’ where it seems that spilled cyanide has reacted with iron in the soil to form Prussian blue, a less toxic breakdown product first isolated by German chemists in 1704 and widely used thereafter as a dye and, in purified form, even in medicine.

It’s because of Prussian blue that cyanide gets its name, from kyanos, a Greek word meaning dark blue, though the deadly forms of cyanide are mostly colourless.

A lot more experience has been gained about using cyanide safely since those days, and you generally won’t find people splashing it around with quite so much abandon.

All the same, Santana hasn’t got any firsthand experience extracting gold with cyanide.

And as for whether our regulators and inspectors of mines are on the ball, there are two words to answer that question, namely, Pike River.

Another concern, though I haven’t read so much about it, is that the price of gold has increased more than eightfold since 2001, even after allowing for inflation.

That’s obviously why Santana is keen right now.

But to what extent do the Santana mine’s economics reflect an expectation that gold prices will stay this high, and what happens if they don’t?

Do we end up with holes in the ground that everyone walks away from? Something like a far larger version of the lakes at St Bathans, formed by earlier goldmining efforts?

That, of course, might not be so bad in the long run if the lakes turn into tourist attractions. Though, having said that, the lakes at St Bathans were mainly created by miners sluicing for alluvial gold, nuggets amid gravel, with hosepipes, and not by cyanide-miners crushing quartz on a modern industrial scale.

(Santana’s operation would use nearly two tonnes of cyanide a day for decades to come, though it is fair to say that a lot of the cyanide gets recycled and reused in the process.)

Whether any new lakes created by the possible financial failure of future open-cast gold mines would be swimmable, or the sort of place you would want to visit to quite the same degree as St Bathans, is a good question.

Finally, one of the most complicated questions is the need to weigh up the value of open-cast gold mining versus the value of central Otago’s environment, for itself, for tourism, and for the attraction of the sorts of skilled workers who like to ride Otago bike trails.

The late Sir Paul Callaghan talks about this issue, from about 17 minutes into the following 2011 classic lecture until the end:

Callaghan said that he wasn’t interested in a one-off $60 billion economic bonus from disruptive mining projects; he wanted to see $40 billion a year added to our economy by intelligent people who value the country’s environment and ‘clean green’ image, and thus choose to live in New Zealand rather than joining the brain drain, or not coming here at all.

All in all, there are a great many complicated questions to answer. And the biggest worry of all is that the Santana proposal is being ‘fast tracked’ in ways that might lead us to miss out on essential safeguards and tradeoffs, ranging from the most mundane, like whether Santana can operate a gold mine properly, to the sort of high-level stuff Callaghan was talking about.

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive free giveaways!