EDINBURGH is a beautiful city, filled with a rich history and the memory of colourful characters. It’s a bit off the beaten track compared to some other cities, but just as worthwhile for a visit!

For one thing, it’s just as historic, if not more so. This year, 2025, it was celebrating its 900th birthday, practically all nine centuries of which have been spent as the capital of Scotland.

My family comes from Scotland on my father’s side, and I’ve been to Edinburgh quite a few times. I was last there when there were Covid restrictions, but my friend Chris also visited Edinburgh just this September, after Berlin, and managed to get some more up-to-date shots, including banners commemorating the 900th anniversary.

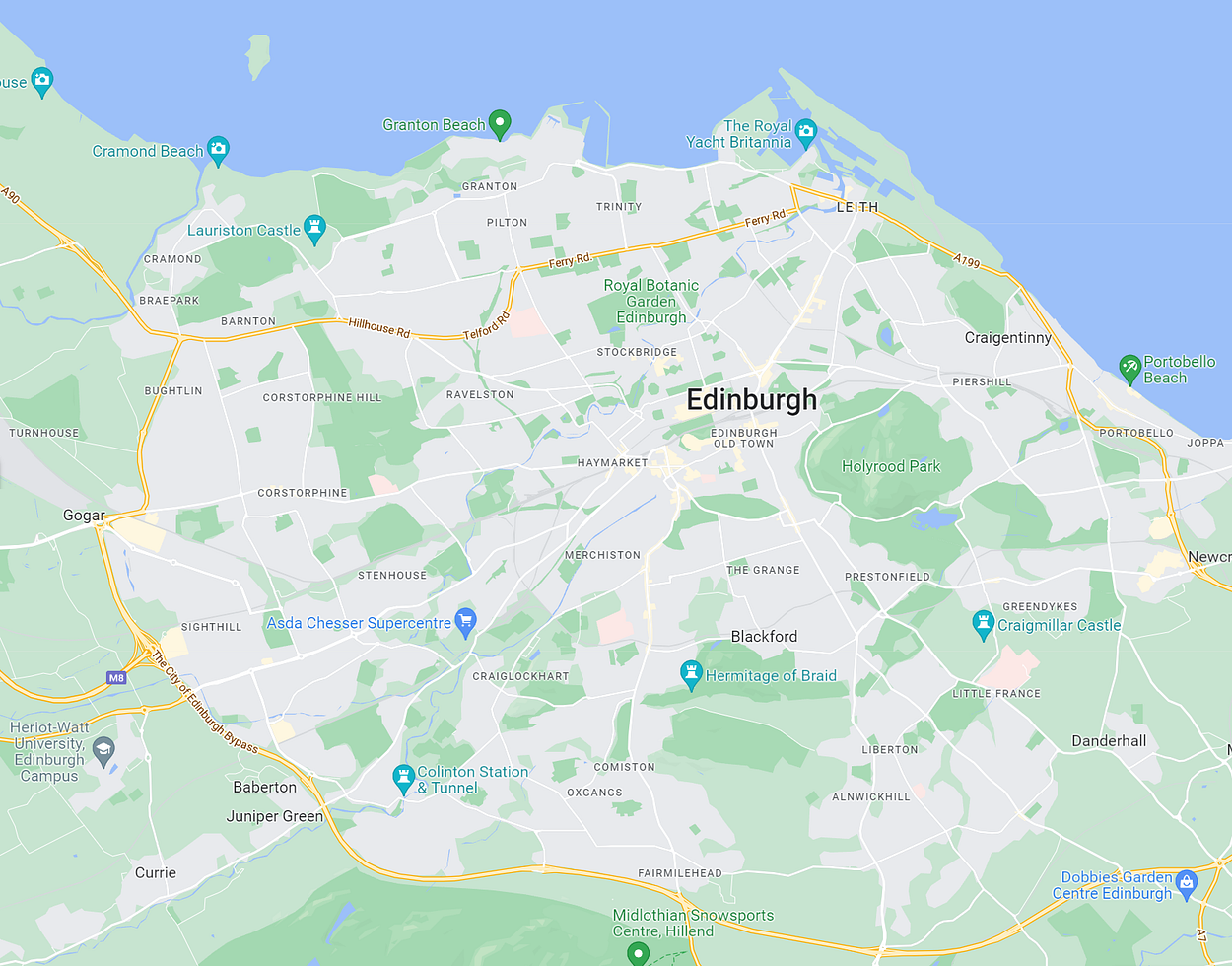

The heart of the city is the Princes Street Gardens, which occupy the site of a former lake and castle moat.

Edinburgh’s main railway station, Edinburgh Waverley, is at the very bottom of the gardens, and you climb up to find yourself in the middle of the inner city.

Edinburgh’s inner city, surrounding Edinburgh Waverley Station and the Princes Street Gardens, is also very compact and walkable.

Church spires and old towers remain the highest buildings, as if not much has changed in centuries, as indeed it has not.

The Princes Street Gardens contain lots of statues, and I was very much struck by a monument to a poet of the 1700s named Allan Ramsay when I was there.

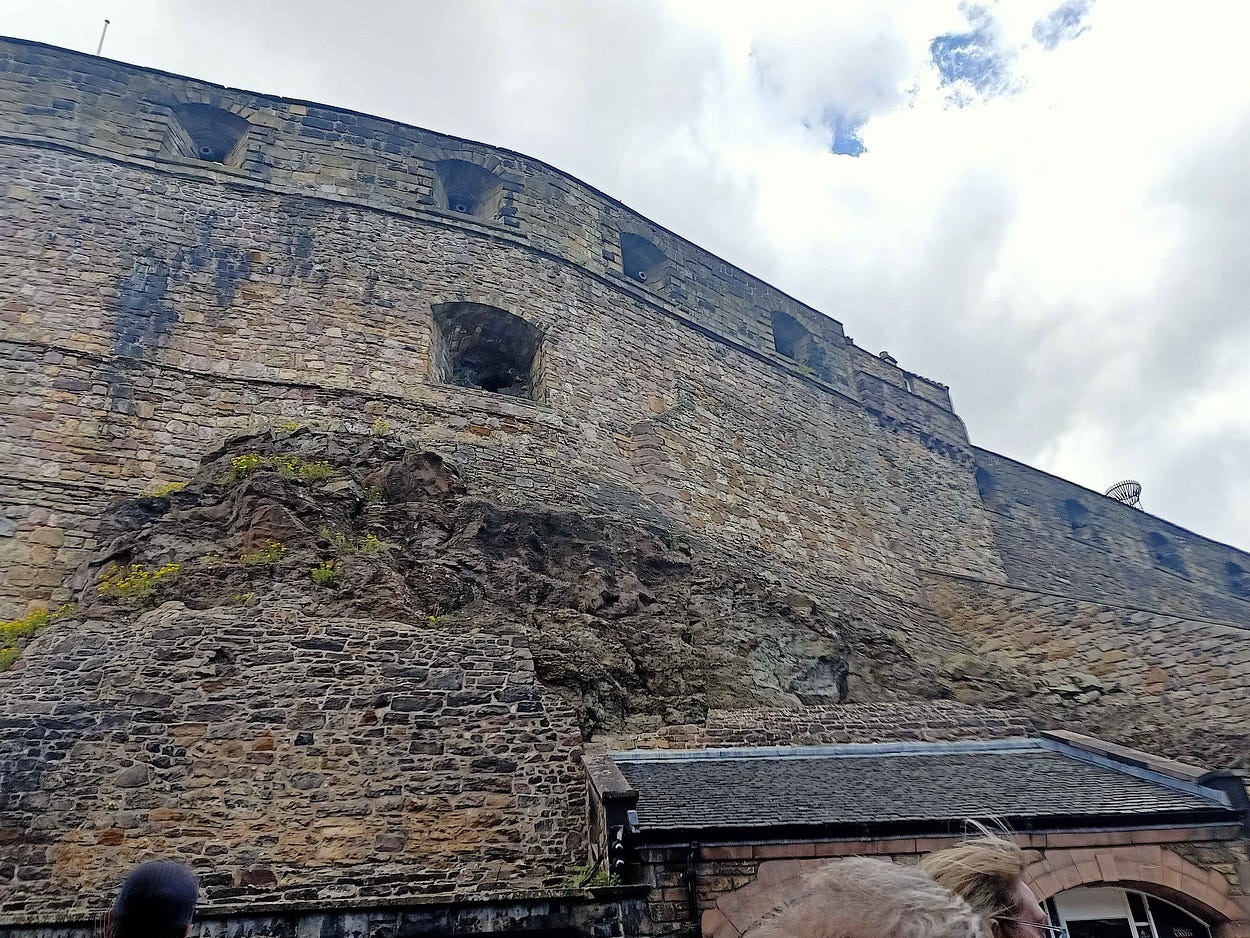

As you can see from a couple of the preceding photos, Edinburgh Castle looms high over the Princes Street Gardens. In the days when the Gardens were a moat, it was Edinburgh Castle that they protected.

On my second-to-last trip, I think it was, I decided no visit to Edinburgh would be complete without visiting the Castle, which is where they also hold the famous Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo!

The closer you get, the more you realise that the Castle really is in quite a lofty position!

Here is the main tourist entrance to the Castle, being guarded by a soldier of the Black Watch, technically now part of the Royal Regiment of Scotland, one of two regiments that take turns guarding the Castle most days.

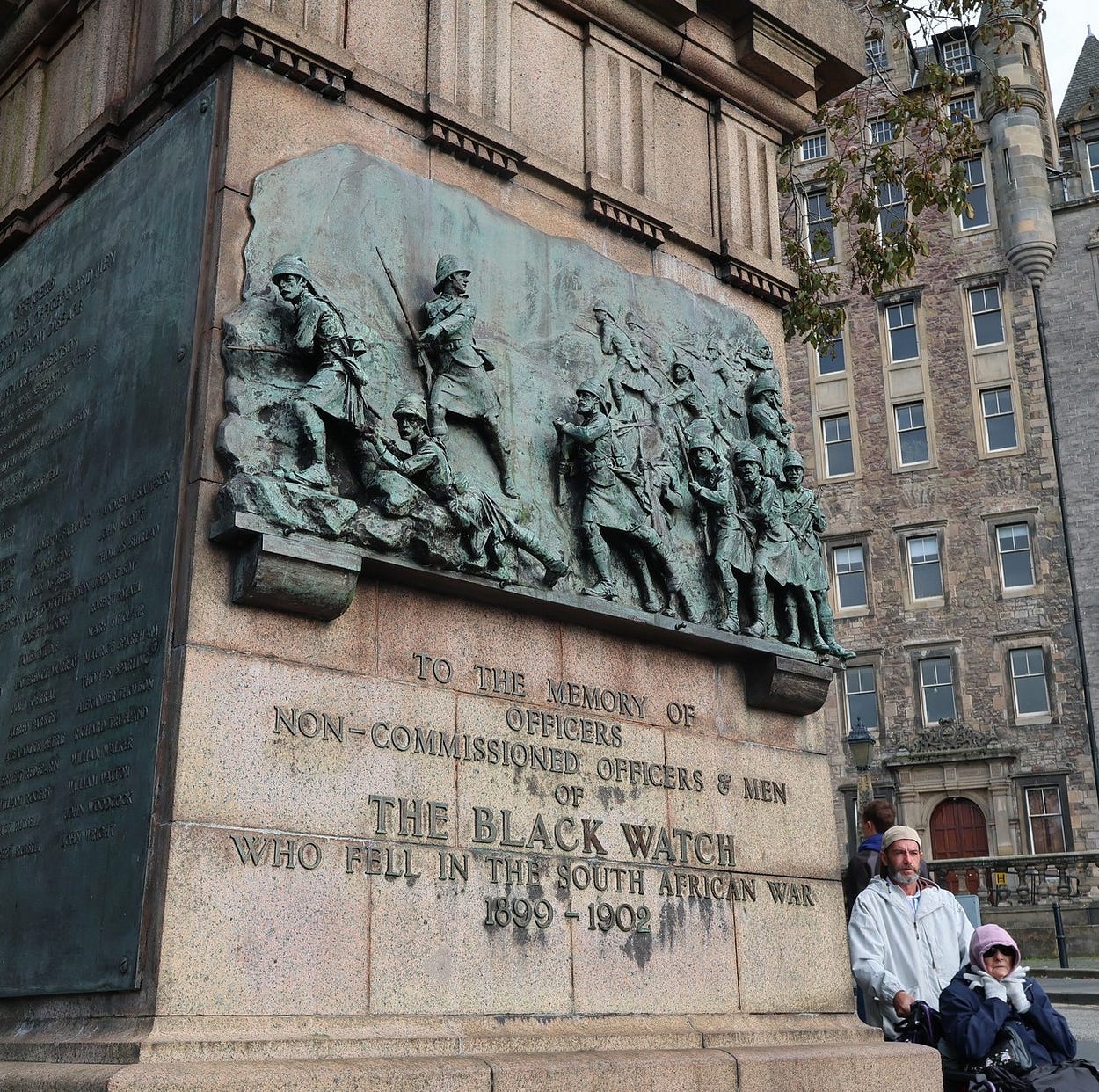

The Black Watch is commemorated in one of the town’s numerous military memorials. My father was in it for a while as a junior cadet.

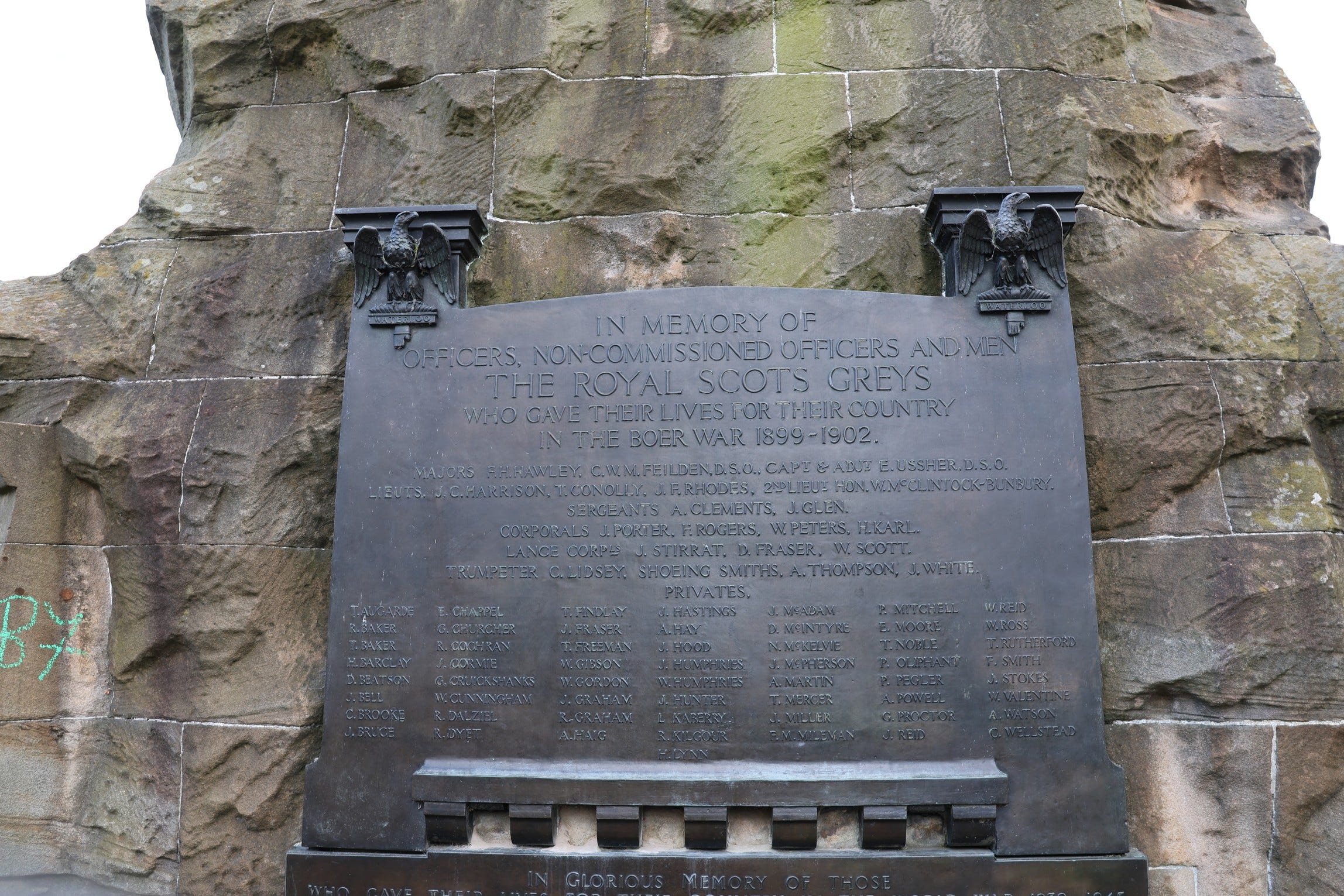

The other regiment that regularly guards the Castle is the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards, descended from the Royal Scots Greys. Both regiments are/were symbolised by an eagle clasping an object called the Spindle of Jupiter, from which, in ancient legend, lightning bolts were emitted.

If this looks like something out of the days of Napoleon, well, it is. The emblem of the Greys is modelled on the eagle atop a French standard captured by a Scottish cavalryman at Waterloo, now held in the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards Museum up at the Castle. The word ‘Waterloo’ appears below Jupiter’s Spindle.

Outfits like the Black Watch and the Greys would always be the first over the top whenever the blood really started pouring.

Luckily, Dad missed out on getting his name on a monument to glory.

Up at the Castle, the entrance is flanked by two statues, of Robert the Bruce and William Wallace, who both fought against the English king Edward I in the Middle Ages when he tried to conquer Scotland.

The red lion above the gate is a symbol of Scotland. The motto, Nemo me Impune Lacessit, means ‘let no-one disrespect me and get away with it’.

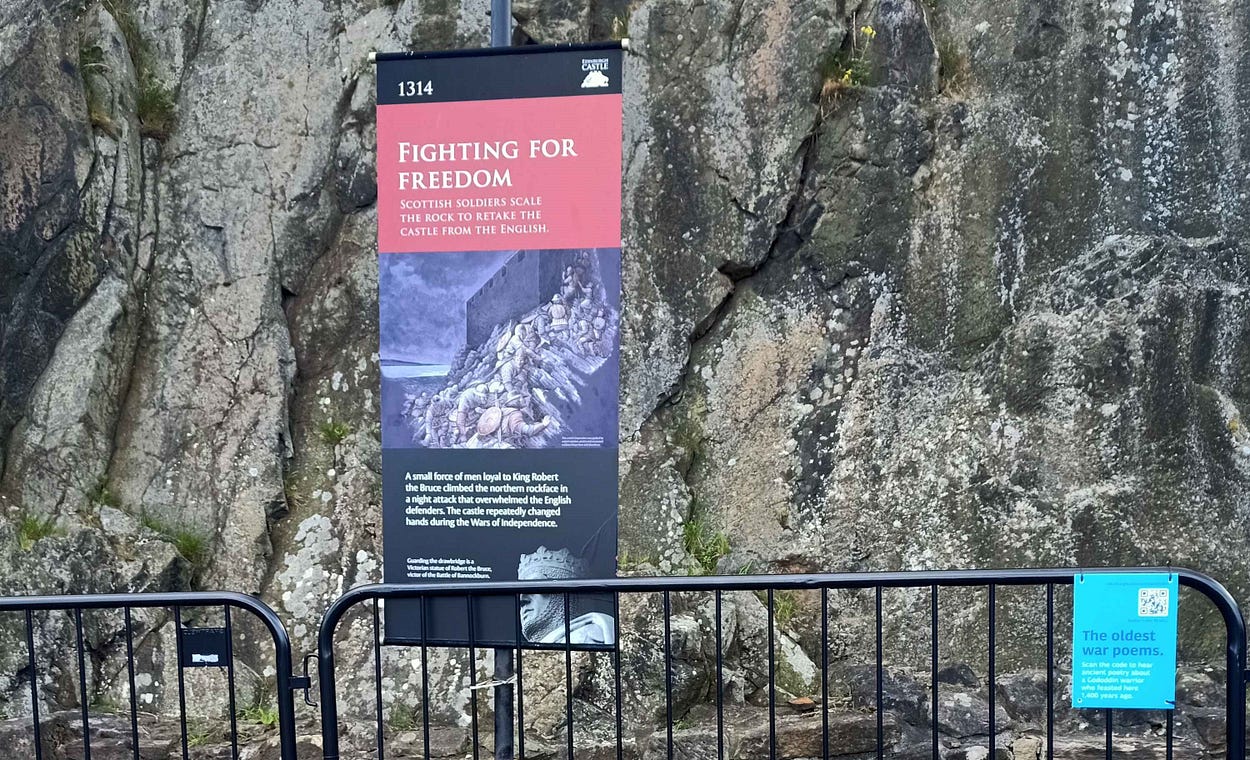

I wonder whether the projecting gutters at the top were used to pour boiling oil on would-be conquerors? These included the Scots themselves when they tried to take it back from the English in a charge led by Robert the Bruce. Another time, when Scotland held the Castle, it was attacked by the English across the moat, after the moat froze over in one of the harsh winters of those days and ceased to be an obstacle (oops!)

The statue that is on the left as you walk in, of Robert the Bruce, was created by a Scottish sculptor named Thomas Clapperton, who also has two works in the New Zealand town of Oamaru: The Wonderland Statue in a local children’s garden, and the statue that was created for Oamaru’s World War One memorial. You can see pictures of those statues in another of my blog posts, here.

So, that’s an amazing Kiwi link with Edinburgh Castle!

The Castle also has cannons, which were last fired in earnest during the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745/46, when the Castle was in the hands of the British government but the city had fallen to the Jacobites, supporters of the Stuart dynasty, which had been ousted after the death of the childless Queen Anne. It’s all very Game of Thrones.

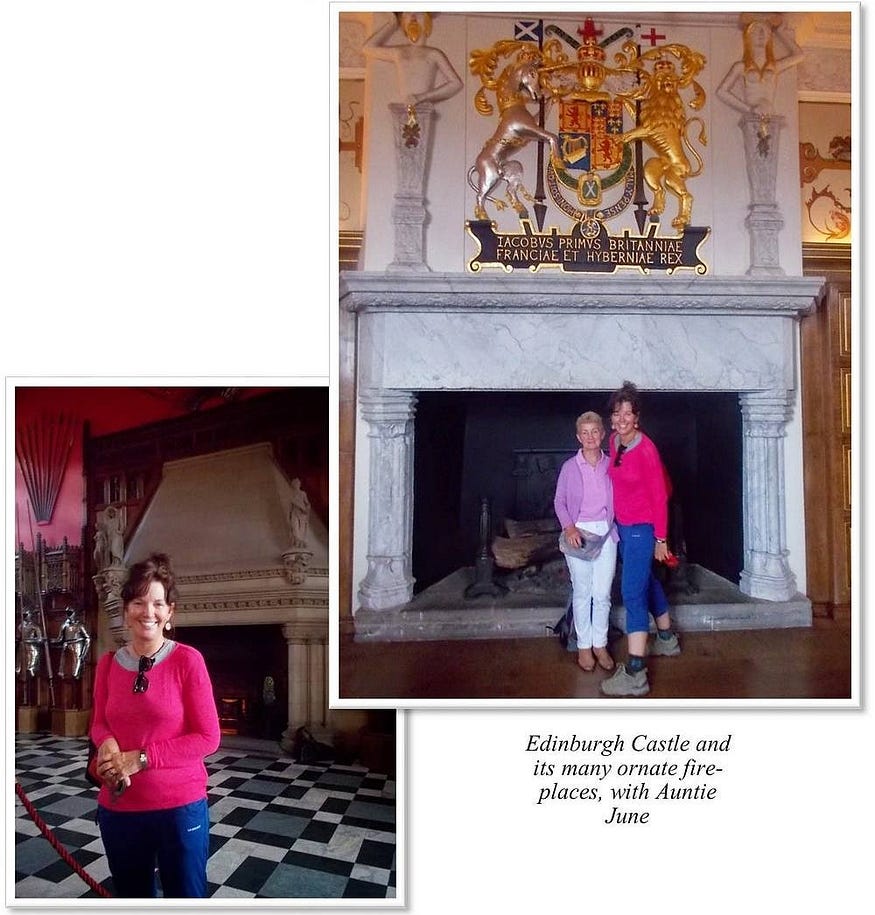

The Castle also has an impressive Great Hall as well as many other sights. These include the Scottish Crown Jewels, which no ordinary person is allowed to photograph.

You can get great views of the city from Edinburgh Castle, as in the next photograph.

I have lost count of the number of times I have visited Edinburgh Castle, but, let me tell you, it never ceases to amaze and thrill me. It includes St Margaret’s Chapel, built in the twelfth century and one of the oldest surviving buildings in Edinburgh.

My grandmother had told my Auntie June stories about how she, when she was a child, used to go to Edinburgh Castle and swing on the gates. I stood at the same gates for a little while and imagined what it would have been like for my grandmother to swing on them.

East of the Castle, there is the Old Town, extending down the pedestrianised and touristy Royal Mile to the Palace of Holyroodhouse, a seat of royal government in Edinburgh in normal times (i.e., when whoever happened to be in charge didn’t have to high-tail it to the Castle and pull up the drawbridge behind the moat), and still the King’s royal residence when he is in Edinburgh.

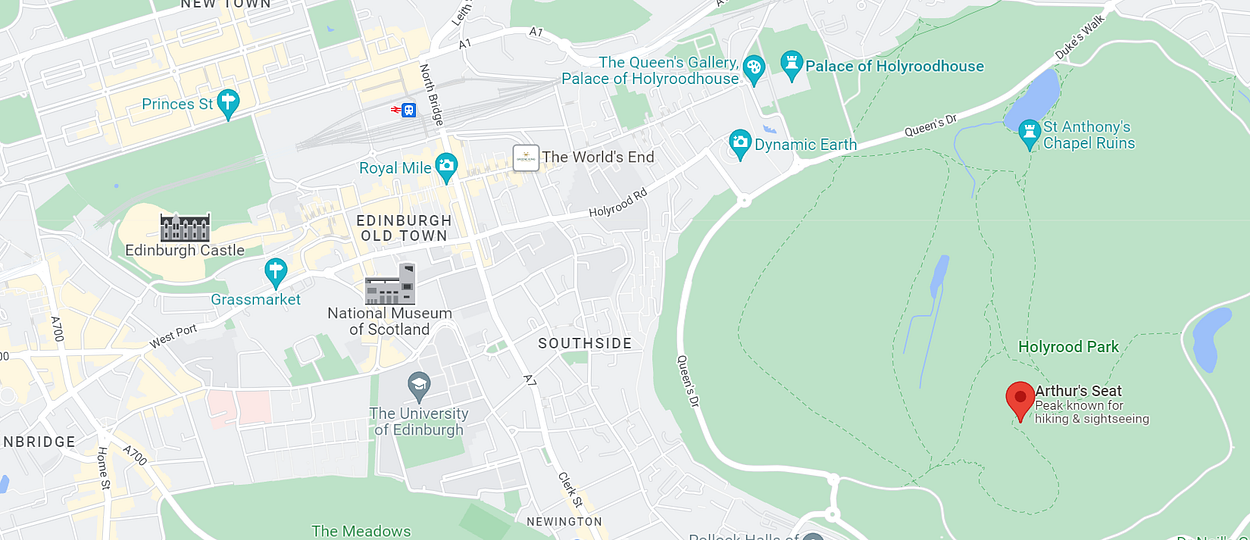

The Palace of Holyroodhouse is next to Holyrood Park, a vast, wild area dominated by a granite peak known as Arthur’s Seat.

The Royal Mile is undoubtedly the most touristy street in Edinburgh. It runs almost due east-west, with the result that the rising and setting sun shine down it spectacularly, in ways that were probably intended at the time, and yield striking street photos today.

There’s a place you can visit underground on the Royal Mile called Mary King’s Close, which its booking site calls the Real Mary King’s Close to emphasise that Mary King was real and not one of the many local figures of legend.

Mary King’s Close has preserved streets underneath the existing ones, as this part of town was built over wholesale in the 1700s. The old mediaeval streets, now subterranean, were abandoned like Pompeii. Well, not quite: a few people continued to inhabit them in dark and unhealthy conditions until the very last occupant left, under a court order, in the year 1902. But basically, they are as they were.

Mary King’s Close is supposed to be really amazing. Chris was going to visit it on his recent trip, but something came up and he wasn’t able to. Next time, though! Here’s a video about it:

Here’s a statue of a real-life old-time plague doctor, George Rae, outside Mary King’s Close, wearing the early equivalent of a modern-day hazmat suit.

The rest of the Royal Mile is lined with quaint old lanes and buildings, including the famous tollbooth, which looks like something out of Harry Potter.

The deer with a cross between its antlers, associated with St Hubert of Liège, which you can see in the photo just above, is also the mediaeval symbol of the Canongate, a section of the Royal Mile after which Dunedin’s main street is also named.

In the middle of the Royal Mile stands St Giles Cathedral, also known as the High Kirk (church) of Edinburgh and, unofficially, the national church of Scotland. Its most distinctive feature is the so-called crown steeple on top, which dates back to the 1400s and also now as much a symbol of Edinburgh as the Brandenburg Gate is of Berlin. (It is actually an English design, but we won’t worry about that.)

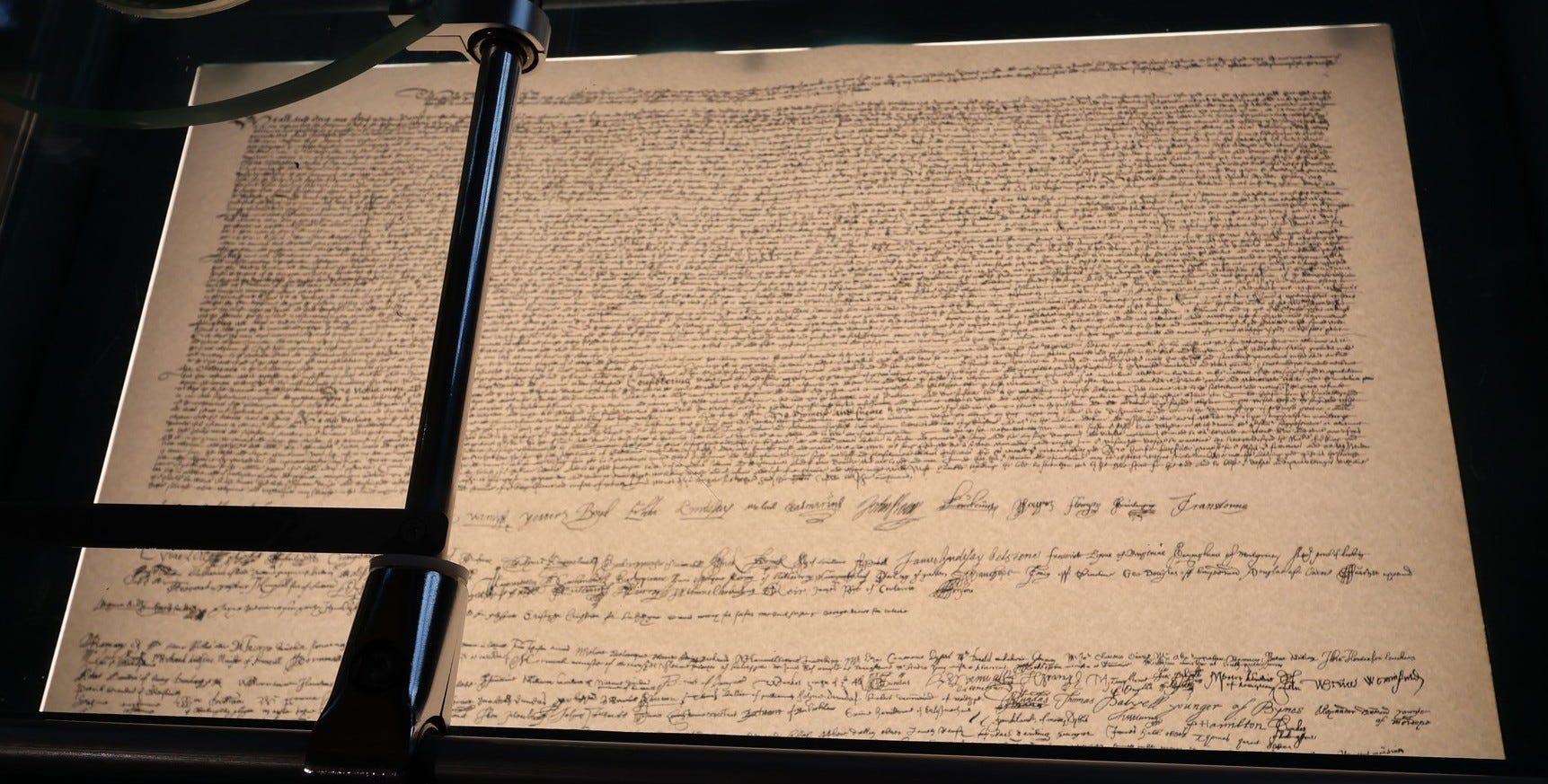

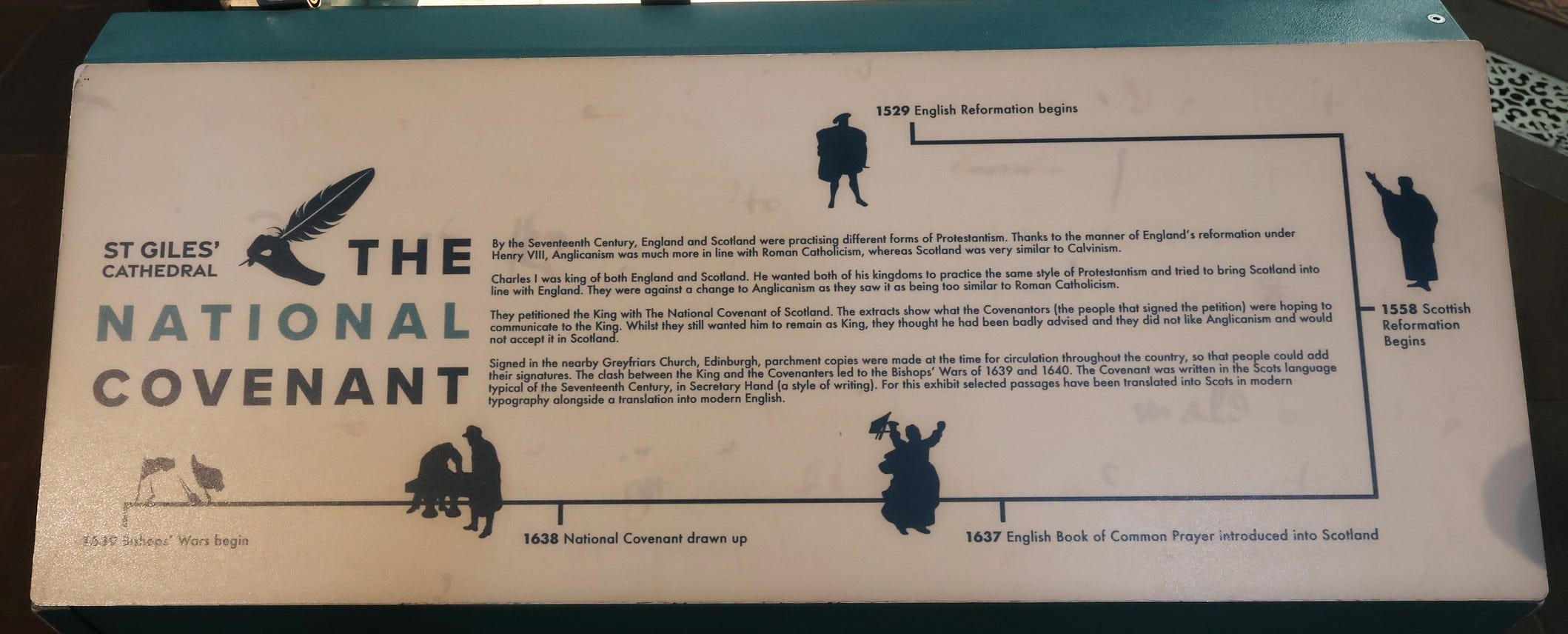

St Giles displayed a copy of the 1638 National Covenant, a grassroots quasi-republican document that led to war between most of the Scots and Charles I, the King of England and Wales, who was also the King of Scotland. A subsequent alliance between the Scots Covenanters and the Puritan Parliamentary forces in England further weakened Charles’s position and contributed to his defeat in the English Civil Wars.

There was also an excellent tomb-relief of the Edinburgh-born writer Robert Louis Stevenson (though he is buried in Sāmoa, of course).

Another display gave thanks for the invention of chloroform anaesthesia by James Young Simpson, licentiate of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh.

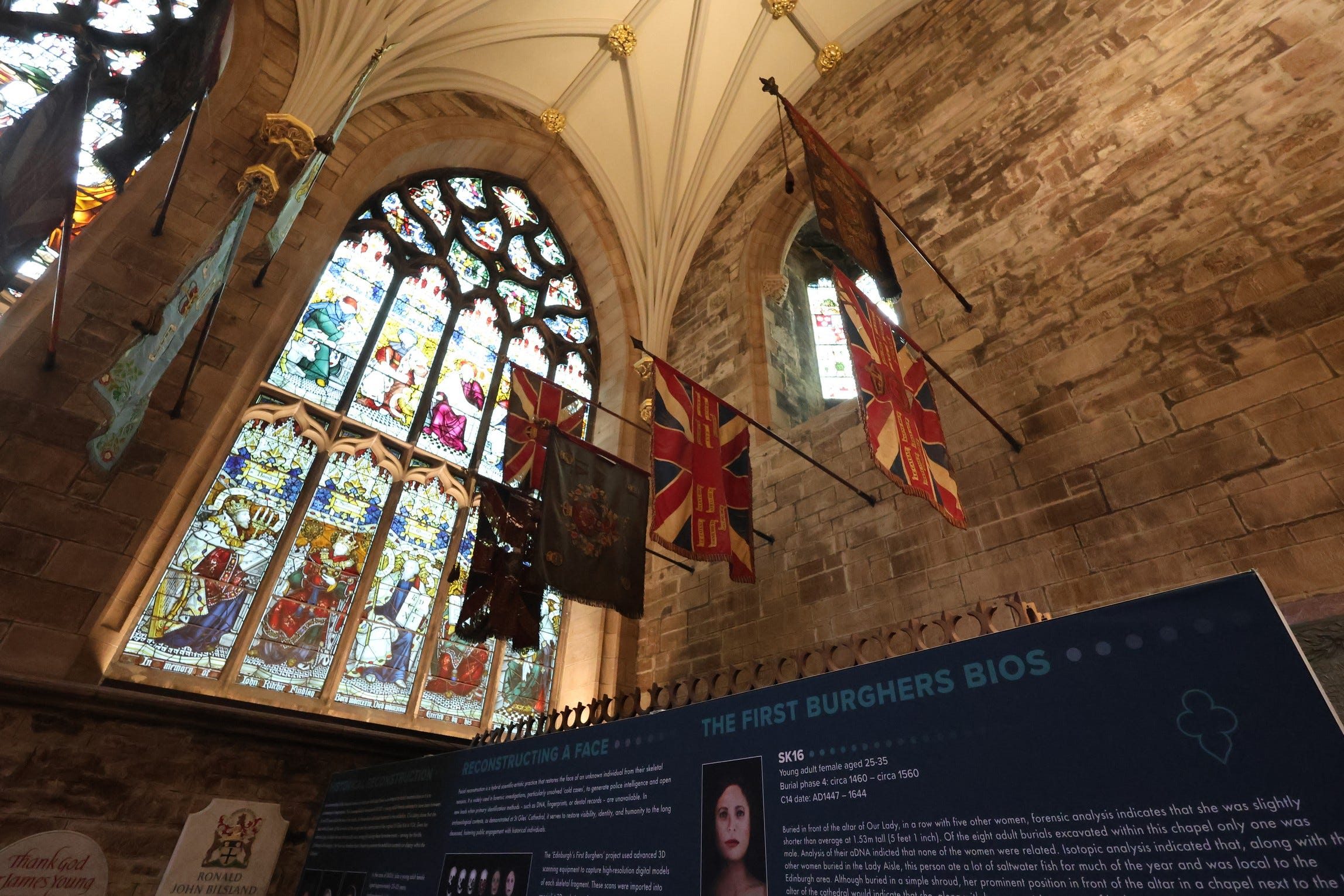

The church contained modern flags, archaeological displays relating findings of the latest dig beneath the city, and the mouldering banners of famous Scottish regiments as well.

All in all, wandering around St Giles was a Scottish history lesson!

Here is another interesting one. The Scots dialect, or language, is like English but full of words that are used differently. For instance, in Scots, flesh is meat but in standard English flesh is what people are made of. So, ‘Fleshmarket’ looks kind of creepy to anyone who isn’t Scottish.

The motto on the next Royal Mile building, in old Scots, says ‘Lvfe God abvfe al and yi nychtbovr as yi self.’ It’s part of the John Knox House, next to the Scottish Storytelling Centre:

Here’s a wider view of the John Knox House, which again looks like something out of Harry Potter, or The Lord of the Rings.

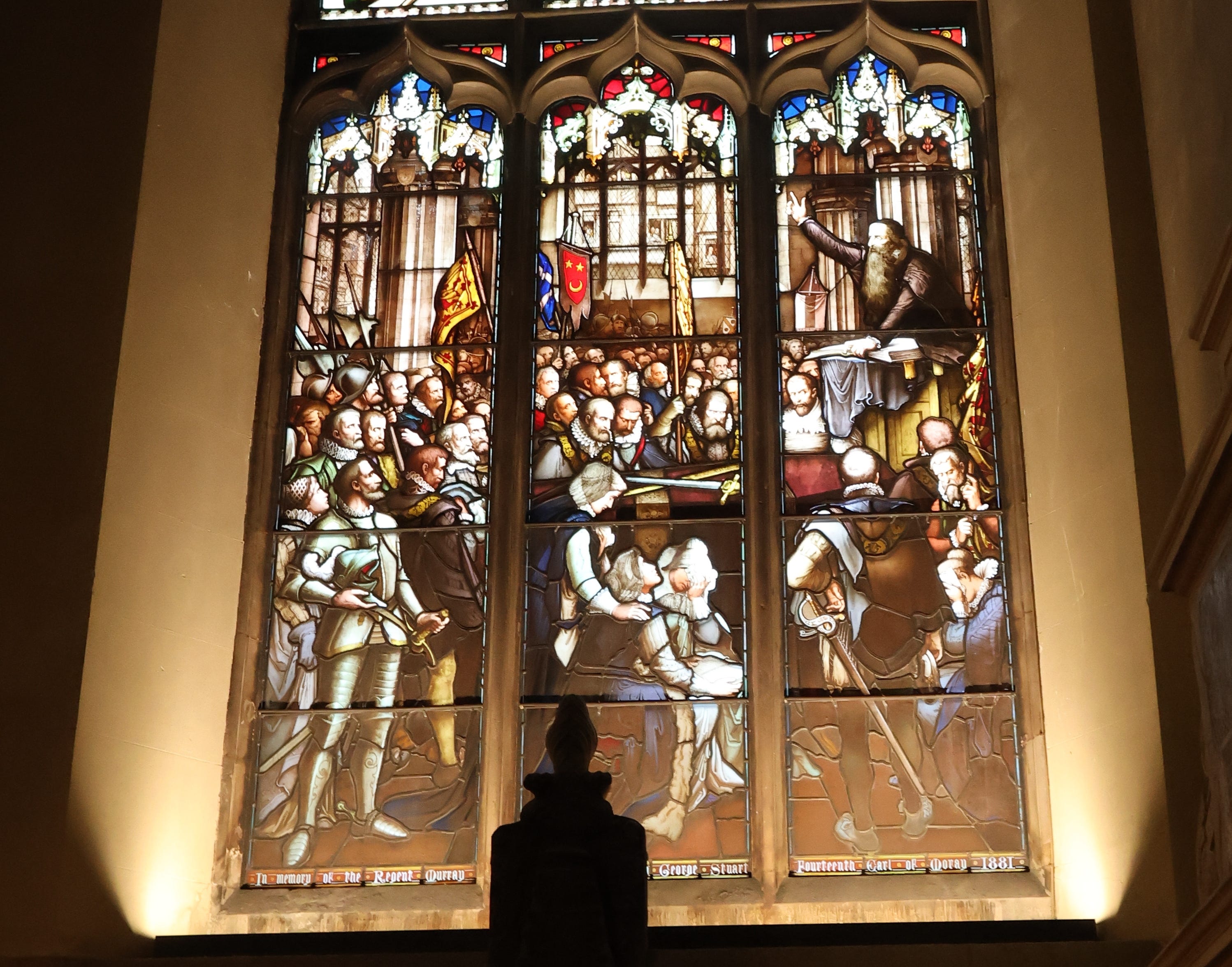

John Knox was the most famous of old-time Scottish Protestant preachers, the Minister at St Giles after the Scottish Reformaton. The next photo is of a section of stained glass in St Giles that depicts Knox delivering an oration, in 1570, for the lately assassinated First Earl of Moray.

Also known as the Regent Murray, the First Earl of Moray was at that time the Regent of Scotland, standing in for the infant king James VI. Moray, or Murray, was also the first head of government to be assassinated with a firearm.

On a lighter note, Knox was denied a visa to enter England, at that time a completely separate country ruled by Elizabeth I, for a certain period after he published an undiplomatic pamphlet called The First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstruous [unnatural] Regiment {government] of Women.

If she were anything like Miranda Richardson’s character in Blackadder, Elizabeth I must have asked Knox, “Who’s Queen?”

And so, finally, to Holyroodhouse. Perhaps its most famous occupant was Mary, Queen of Scots, the queen whom Elizabeth I of England imprisoned in the Tower of London and then beheaded. When I was there last, the great complex of Holyroodhouse included the Queen’s Gallery, which is now an art gallery.

It’s since been renamed the King’s Gallery, now that Britain has a king and no longer a queen.

Here is a photo of the Palace of Holyroodhouse, from the front. It also shows an ornate fountain, which appears to be off to one side but is actually in the middle of the forecourt.

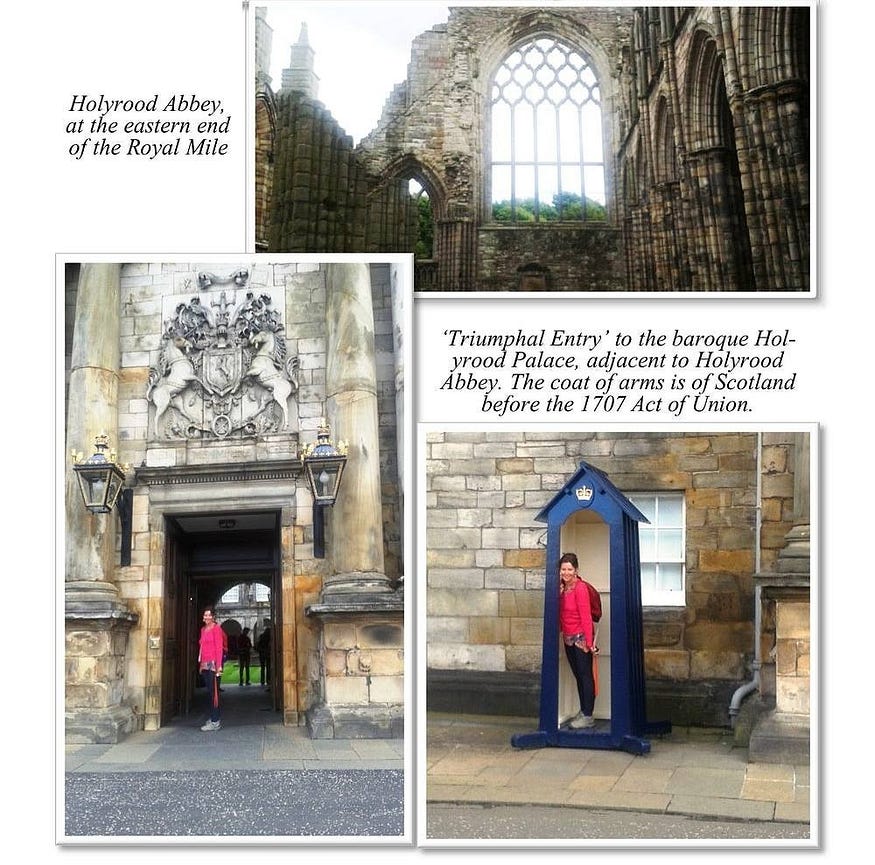

The front entrance is known as the ‘Triumphal Entry.’ It’s guarded by a couple of blue sentry-boxes, though they are not always occupied. They have little crowns on top, so perhaps they only use them when the King is staying.

There is also a ruined abbey nearby, Holyrood Abbey. The next image shows Holyrood Abbey and a couple of photos of the Triumphal Entry and one of its sentry boxes, with myself inside each.

Here are some photos taken on the same trip as above, showing the quadrangle inside the Palace of Holyroodhouse, plus the fountain.

These collages, plus the one in Edinburgh Castle and another further on about the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, were originally made for my book A Maverick Pilgrim Way.

The next crest is that of the sixteenth-century monarch James V (r. 1513–1542), one of the most notable Scottish kings and the father of Mary, Queen of Scots, his initials shown as I R 5. Legend had it that only a monarch could command a unicorn, shown duly chained, and so the unicorn was an important symbol of Scottish royal authority in those days.

The grand fountain in the forecourt of the Palace of Holyroodhouse is a Victorian replica of a fountain originally built for James V at the now-ruined Linlithgow Palace.

I wasn’t able to enter the palace because of Covid restrictions when I was there last. And Chris didn’t go inside on his recent trip because it cost 25 pounds to enter, and he didn’t want to shell out so much just to go inside. He probably should have coughed up all the same.

Here is a video of my rambles through the Castle, the Royal Mile, up Arthur’s Seat (about which I will have more to say in my next Edinburgh post), and in front of the Palace of Holyroodhouse. This was when I couldn’t get into Holyroodhouse. But you could still watch the changing of the guard.

Across the road, there sits the Scottish Parliament, which, in contrast, is free to go inside.

On the earlier visit, when I was able to get into Holyroodhouse, I also went to the Fringe Festival held annually in Edinburgh, which I loved.

The Fringe Festival began in the 1940s as an add-on to an official, but rather stuffy, festival of the arts held in Edinburgh. The Fringe Festival showcased the acts that didn’t make it into the official Edinburgh Festival. It soon acquired the reputation of being the more interesting place to hang out!

I did a post about Edinburgh’s festivals, which has more videos in it, here.

So, Edinburgh isn’t all old stuff by any means!

This post combines material that appeared in an earlier post, now unlisted, with material from my friend Chris’s recent visit to Edinburgh. Next week‘s post will be about a mining proposal at Tarras, near Queenstown. The week after that, I’ll be returning to Edinburgh, writing about an ascent of Arthur’s Seat and of the nearby Calton Hill, and why Edinburgh is called ‘The Athens of the North.’

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive free giveaways!