AFTER arriving in Berlin on the S-Bahn from Potsdam, I caught another S-Bahn train to the eastern Berlin suburb of Friedrichshagen, about 18 km southeast as the crow flies and close to the edge of the built-up area.

Tram tracks ran right past the front of the S-Bahn station at Friedrichshagen.

In Berlin and its hinterland, if you see tram tracks running on the streets, it is a sign that you are on the territory of the former Communist East Germany. In the former West Berlin, all the trams were ripped out in 1967 and have never since been replaced. This is one of many surprisingly persistent differences between East and West Berlin, and East and West Germany, even some 35 years after the fall of the wall.

Just as in Potsdam, also part of the former East Germany, it was amazing how many trams there were out here in Friedrichshagen, and how many people rode bikes as well.

The next photo shows a tram passing through Friedrichshagen. You can see more bicycles in the background, masses and masses of them.

At Friedrichshagen, an underpass below the S-Bahn tracks led to a rural tram, Route 88, advertised as ‘The Tram in the Green’ because it passes through a forest. Route 88 runs through the town of Schöneiche to the village of Alt-Rüdersdorf, more than 14 km further on into the countryside from Friedrichshagen.

Here’s a video of a walk through the middle of Friedrichshagen, and then of a couple of rides on Route 88.

Route 88 was founded in 1910, at a time when Schöneiche, which means ‘pretty oaks,’ was a country getaway.

After the fall of East Germany in 1990, Route 88 was deemed uneconomic and was nearly closed around the year 2000. But pressure from locals kept it running. It is operated by a local company called SRS, which also runs a shorter rural tramway to a nearby town called Woltersdorf.

After my ride on Route 88, I headed back into the centre of Berlin on the S-Bahn, getting off at Alexanderplatz. The letter U in the next photo indicates Alexanderplatz’s U-Bahn or underground railway station.

This is not the same as the Alexanderplatz S-Bahn station: the S-Bahn is a separate system (though covered by a common ticket), and the Alexanderplatz S-Bahn station is actually elevated above street level.

Alexanderplatz features in a lot of gritty detective novels and dramas set in 1920s Berlin. The fashion was kicked off in 1929 by Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz, the very year in which the first two or three series of Babylon Berlin, the latest homage to the genre, are set.

That’s because the headquarters of the Berlin police used to be in a huge red building in the Alexanderplatz, known to detectives and criminals alike as the Alex; though these days the Alex is more modest.

That photo shows how the Berlin trams run right through the middle of the Alexanderplatz (so it pays not to daydream), while the S-Bahn trains run above it to the above-ground S-Bahn station.

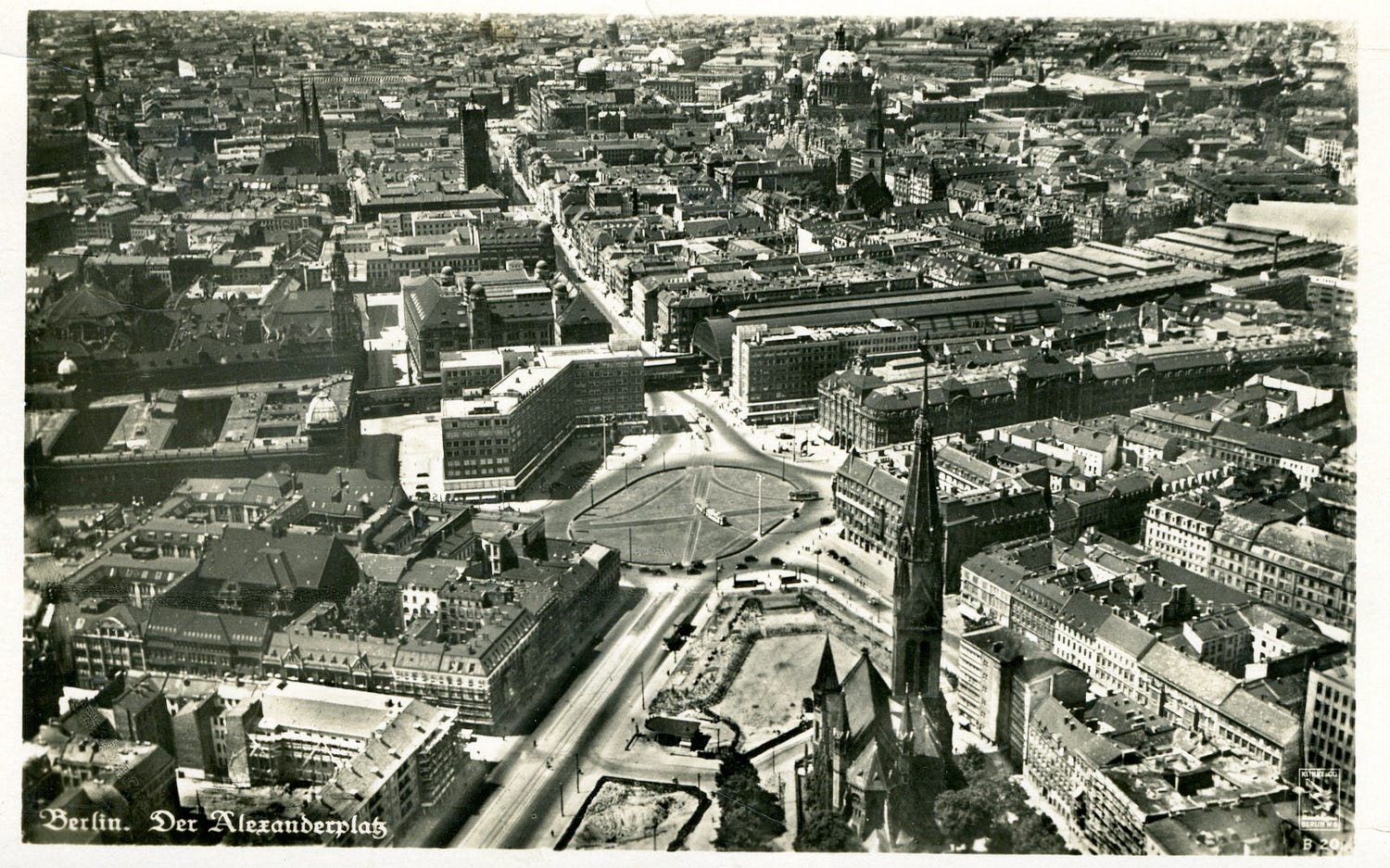

That’s a really iconic Alexanderplatz shot. You see the same crossover even in the old photos taken in Babylon Berlin days, such as this postcard from about 1930, looking in broadly the same direction, with the high dome of the Berlin Cathedral in the background and the now-ruined Franciscan Monastery Church in the foreground.

The original Alex police station was wrecked in World War II, and pulled down thereafter. The similar-looking ‘Rotes Rathaus’ or ‘red town hall,’ which still stands a few blocks away, stood in for it in the making of Babylon Berlin. Apparently, the Rotes Rathaus looks really gorgeous at sunrise and sunset, just like the towers I photographed opposite the Yachthafen Potsdam.

However, the Communist regime did contribute a couple of landmarks of their own to the Alex.

One is the massive TV tower a couple of hundred metres away. The other is the 24-hour world clock, which you can also see in the next photo, just to the left of the centre with the curved-roofed S-Bahn station behind.

Nearby, stands the Haus des Lehrers, or house of the teacher, an early-sixties East German building with impressive murals, created for it in 1964 by the artist Walter Womacka, that emphasise the importance of learning.

As the name Karl-Marx-Allee suggests, a lot of the old East German street names have been retained as well.

The Haus des Lehrers is next to a curiously domed building from the same era called the Congress Hall, which seats 1,000 people under its dome in a room called the Kuppelsaal.

The buildings in the background have the rather utilitarian look of East German apartments, known as Plattenbaue, a word that means prefabs. Of course, there was a lot of rebuilding that had to be done in a hurry after the war, so that might explain why things were not too fancy.

Diagonally across Karl-Marx-Allee from the Haus des Lehrers, there was another mural, more sculptural this time, that celebrated Communist cosmonauts.

However, even if the murals are good, I hadn’t really come all the way to Berlin to look at a lot of rather dreary 1960s architecture, as there is no shortage of that sort of thing in Auckland.

Instead, I wanted to check out a much more distinguished historical precinct that had somehow survived the war, along the streets known as Under den Linden and its eastward continuation, Karl-Liebknecht-Strasse.

Karl-Liebknecht-Strasse is another of those streets that still has a Communist name. It honours a famous founder of the German Communist Party, Karl Liebknecht, who was murdered by right-wing forces in January 1919 along with his colleague, the even more famous Rosa Luxemburg, a perceptive critic of the dictatorial tendencies already evident in Communist Russia, who contended that “Freedom is always and exclusively freedom for the one who thinks differently.”

Though a lot of the things Luxemburg said might well have been dusted off and aimed at the later East German regime as well, that did not stop her name cropping up on the map of East Berlin, too.

(It’s also said that Rosa Luxemburg delegated first impressions of people to her cat, the cat being, apparently, an infallible judge of character. Supposedly, the cat hated Stalin, who, I imagine, might well have aimed a swift kick at it when nobody was looking.)

Though I should have headed straight down Karl-Liebknecht-Strasse, I got a bit lost and wandered about all over the place, my phone GPS not working because I had run out of roaming data or something like that.

Which was, in a way, just as well, because I came across things I wouldn’t have come across otherwise, such as lively back-streets and the Hackescher Markt.

There were also many reminders of Berlin’s history.

For instance, a workers’ café built at the beginning of the 1890s, the Volks-Kaffee-und-Speise-Hallen-Gesellschaft, or people’s coffee and dining halls company, designed by the architect Alfred Messel and intended to be accessible to ordinary people, unlike the posh and expensive Viennese cafés. (There’s a building of roughly the same age in Wellington’s Cuba Street called the People’s Palace, which probably served a similar function.)

I also came across an early headquarters of the German Communist Party,

And so to the architecturally distinguished precinct, which was not limited to Unter den Linden, the grand avenue I covered last week.

For instance, a couple of blocks off Unter den Linden, there is the Gendarmkenmarkt, “arguably Berlin’s most beautiful square.” The Gendarmenmarkt is bookended by two notable cathedrals, the French Cathedral and the German Cathedral, while the Konzerthaus Berlin forms the third side of the square.

The Konzerthaus is a notable building by the neoclassical architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel, who designed, or co-designed, several others in this precinct, along with the Nikolaikirche in Potsdam.

I’m kind of kicking myself that I never made it to this spot!

The Gendarmenmarkt was restored by the East German regime, which in 1987 staged a tattoo in a mixture of modern and historical uniforms on the steps of the Konzerthaus to celebrate the 750th anniversary of Berlin: a city that was unfortunately still divided at the time and would be for another two years (there were parallel celebrations in West Berlin).

Another reminder of history that I came across from time to time in the older residential district was Stolpersteine, a word that means ‘stumbling stones,’ though they are made of bronze. These are bronze memorials set in the footpath to honour people, mostly Jewish, who either fled or were murdered in the Nazi era.

In the residential district, I also saw signs for organisations that helped people find accommodation and defended the rights of renters, a very large and well-organised percentage of the German population.

The next photo shows some rather classy-looking apartments run by the BWV or Beamten-Wohnungs-Verein zu Berlin, a 125-year-old agency that provides accommodation for public servants posted to the capital.

Like several other countries in Continental Europe, Germany has missed out on the worst excesses of post-1980 neoliberalism and housing speculation.

Many things that would have been privatised in English-speaking countries, such as the BWV if we had had its equivalent, are still regarded as a public service or public utility and are still chugging along accordingly.

This includes public transport that is truly public. An ad for the Berlin public transport system, which I also saw in my detour, says ‘It’s the togetherness that counts — just for all,’ in other words, a play on the ‘just for you’ of commercial advertising, while emphasising the sociable qualities of public transport as well.

But this is not to say that the spirit of enterprise does not exist at all. Thus, I also saw an ad for a real estate company that looks as though it has spotted an opportunity in do-ups. There‘s a lot of scope for that sort of thing in the East.

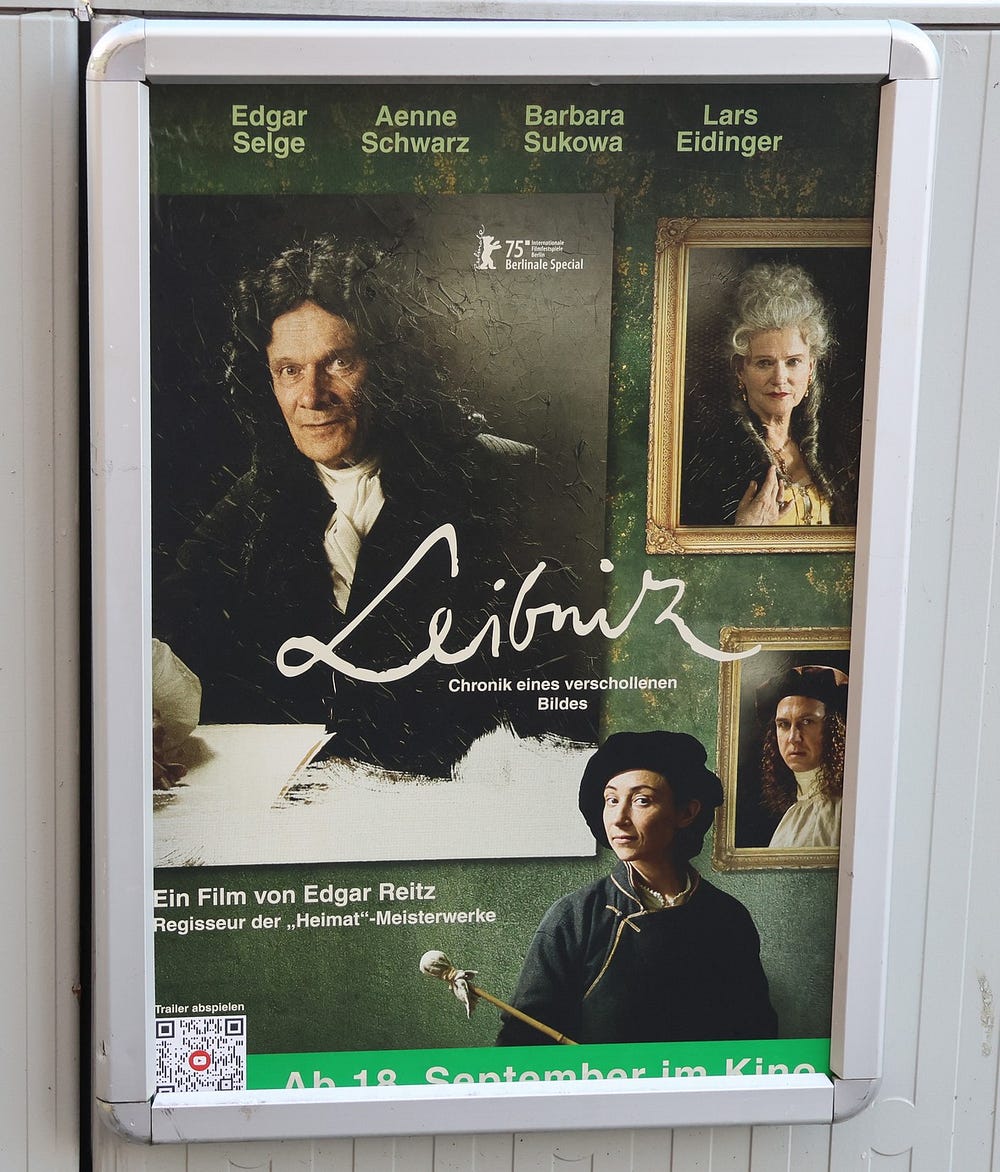

I also saw ads for plays and films that might be regarded as a bit unfamiliar or highbrow by New Zealand standards, such as a comedy by Molière called ‘The Imaginary Invalid.’

And a biopic about Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Germany’s equivalent of Sir Isaac Newton, which is quite well regarded but unlikely to be screening in the multiplexes any time soon.

I remember someone saying that Berlin was one of the few places where a night out drinking makes you smarter.

Which is perhaps also why Kiwis who aren’t particularly interested in rugby, real estate, and the price of milk quite often emigrate to Berlin despite the language barrier, and don’t come back.

Near the Marienkirche, the TV Tower, and the red town hall, I also wandered past a park in which there was a famous statue of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, the Marx-Engels Forum; though, unfortunately, it was being renovated at the time.

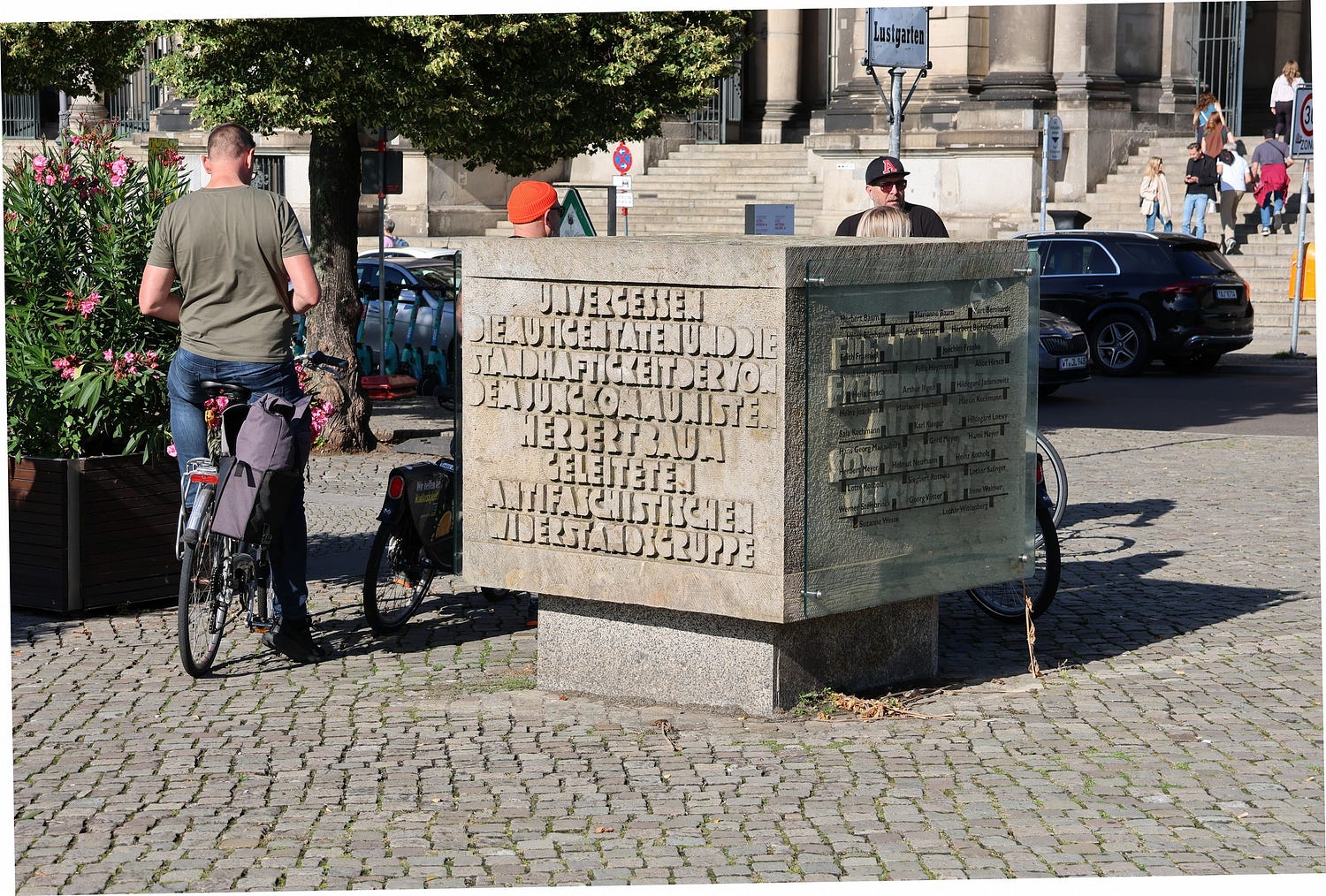

As I mentioned in my last post, in front of the Berlin Cathedral, there is the Lustgarten, a word that means garden of innocent but hearty pleasures; it’s one of those foreign words that can easily be misunderstood.

The Berlin Lustgarten was the site of an anti-Nazi protest in 1942, in which some militants in a mostly Jewish and somewhat left-wing group led by Herbert Baum set fire to a Nazi propaganda exhibition in the Lustgarten. Tragically, most were caught and executed. An East German monument makes out that they were all Communists, but that wasn’t really true.

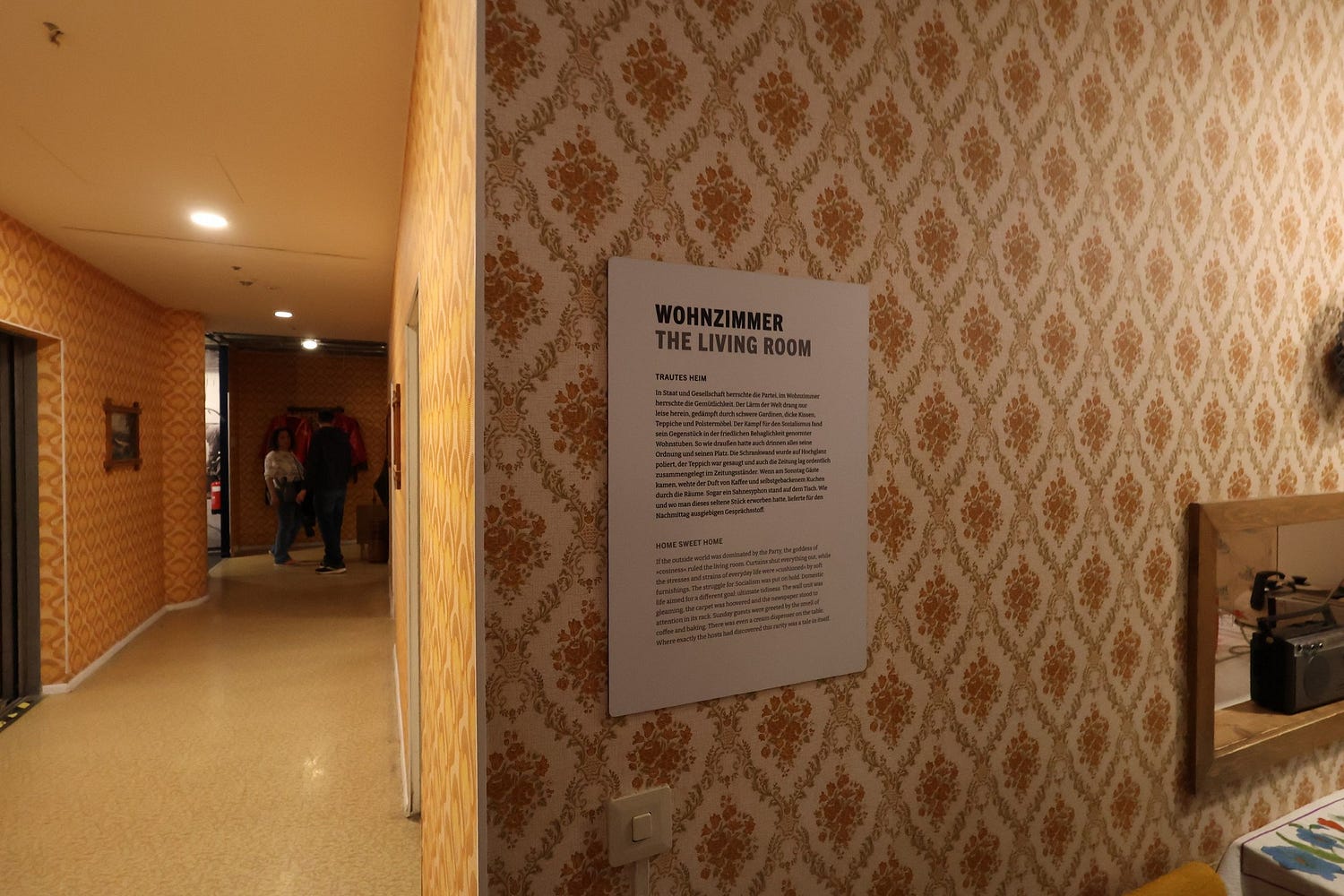

On the other side of the Berlin Cathedral, there is the DDR Museum, DDR being the German initials for Deutsche Demokratische Republik, or German Democratic Republic, the official name of the former East Germany.

The DDR Museum was full of old posters and other exhibits.

There was a replica East Berlin flat with awful 1970s decor, which possibly had more to do with it being the 1970s than Communism. Actually, a university lecturer told me that the East Germans were quite well housed once wartime shortages were overcome, though he might have been a left-wing academic.

Of course, the most notorious thing about East Germany was the Berlin Wall, along with equivalent fortifications along the whole of the frontier with the former West Germany.

The background to the wall, and the wider border fortifications, was that the East German economy lagged behind that of West Germany, and ultimately resorted to coercion as a way of keeping too many skilled workers from emigrating to the West.

Along with whatever inefficiencies were introduced by replacing markets with planning (though the West German economy also had a large state sector), East Germany was already historically the poorest part of postwar Germany: a region lacking in energy and natural resources and with much of its land either sandy or a swamp.

Furthermore, East Germany did not receive Marshall Plan aid from the Americans and had to pay heavy reparations to the Soviet Union instead.

The result was a damaging exodus of skilled labour to West Germany, to which the East German government eventually responded by fortifying its frontiers with the West.

All this was supposedly designed to keep Westerners out, but existed, in reality, to keep the East Germans, especially the most highly skilled ones, who could earn much more in West Germany, in. It was a system of prison walls that made East German Communism look terrible, and also went a long way toward bankrupting the already-handicapped East German economy, both directly in terms of its cost, and indirectly by sterilising a significant part of the country’s land area. And, of course, blocking trade.

In fact, the regime’s obsession with walling its people in distracted attention from the fact that not everything in East Germany was terrible. Notably, the position of women was better than in West Germany, where until 1977, married women needed their husband’s consent to get a job.

As all those murals suggest, there was also much more respect for science than in many Western countries. And housing was provided almost for free.

It is one of the ironies of history that the East Germans wouldn’t have needed all those fortifications to keep their people in today, if they had just kept on providing them with cheap housing. Then they really would have had to keep Westerners out.

Another display described the multiplicity of organisations to which people were expected to belong in the East, an obviously much more regimented society than the West.

Some of these organisations still exist, notably Volkssolidarität, which looks after old people. Here’s a photo I took of one Volkssolidarität branch out in the street.

Inside the museum, there was also a souvenir shop.

I should have bought the T-shirt!

The Berlin Palace is next to the ESMT business school, located in a former headquarters of the East German government, in which the stairwells are full of stained glass murals extolling the virtues of Communism. I guess that’s the trouble with buying anything pre-loved, you have to put up with the former owners’ quirks.

The words you can see on the windows, trotz alledem, mean ‘in spite of everything,’ the title of the last article written by Karl Liebkecht before his murder. The two faces above the words are Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg.

You can go all the way up the stairs if you can secure someone to guide you, but I was only able to get a picture from the ground floor.

Finally, I got back to Potsdam at nightfall, to watch a party boat heading down the River Havel from my campground at the Yachthafen.

There were a whole lot of other things I wanted to get to see, various monuments, palaces, and other interesting housing projects, but of course, one day was not enough! It was amazing what I did manage.

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive free giveaways!