ONE thing you quickly learn about Edinburgh, whose 900th anniversary I wrote about last week, is that there’s plenty of opportunity for hill-climbing and dizzying views looking down. Such as, for instance, this view of Edinburgh Waverley Station from the top of a climb called Jacob’s Ladder.

Apparently, there are no fewer than 49 named hills and mountains in Edinburgh.

This is because Edinburgh’s geology is a mixture of hard volcanic rock, such as granite, and softer sedimentary rock, such as sandstone. The soft rock was scooped out by ice-age glaciers to form hollows called ‘glacial scoops,’ while the hard rock ended up standing proud.

Starting from Princes Street and its famous Gardens, located in a glacial scoop that also contains Waverley Station, you can walk up Waterloo Place, over the Regent’s Bridge (“commenced in the ever memorable year 1815”) to Calton Hill, one of the most famous of Edinburgh’s many hills.

Here’s a photo of a great mass of tourists making the last leg of the climb up Calton Hill, toward a monument to the philosopher Dugald Stewart on top.

Once at the top, you get the views I mentioned in last week’s post, of the downtown and its many spires.

And out toward Arthur’s Seat, which I’ll have more to say about in a moment, as I climbed it one time I was there.

And, in another direction, out over the Firth of Forth.

Somewhat to their surprise, perhaps, tourists who struggle toward the top of Calton Hill, in search of great views over the city, will also discover a cluster of neoclassical architecture from 200-odd years ago. Or in other words, architecture that revived the styles of ancient Greece and Rome.

Architecture that also gave rise to the saying that Calton Hill was Edinburgh’s Acropolis. And that Edinburgh itself was the ‘Athens of the North.’

Take, for instance, the complete set of buildings on Regent Road, near the top of Calton Hill, that appears in the next photograph. It was built to house Scotland’s Royal High School, one of the oldest schools in the world (founded 1128) from 1829 to 1968.

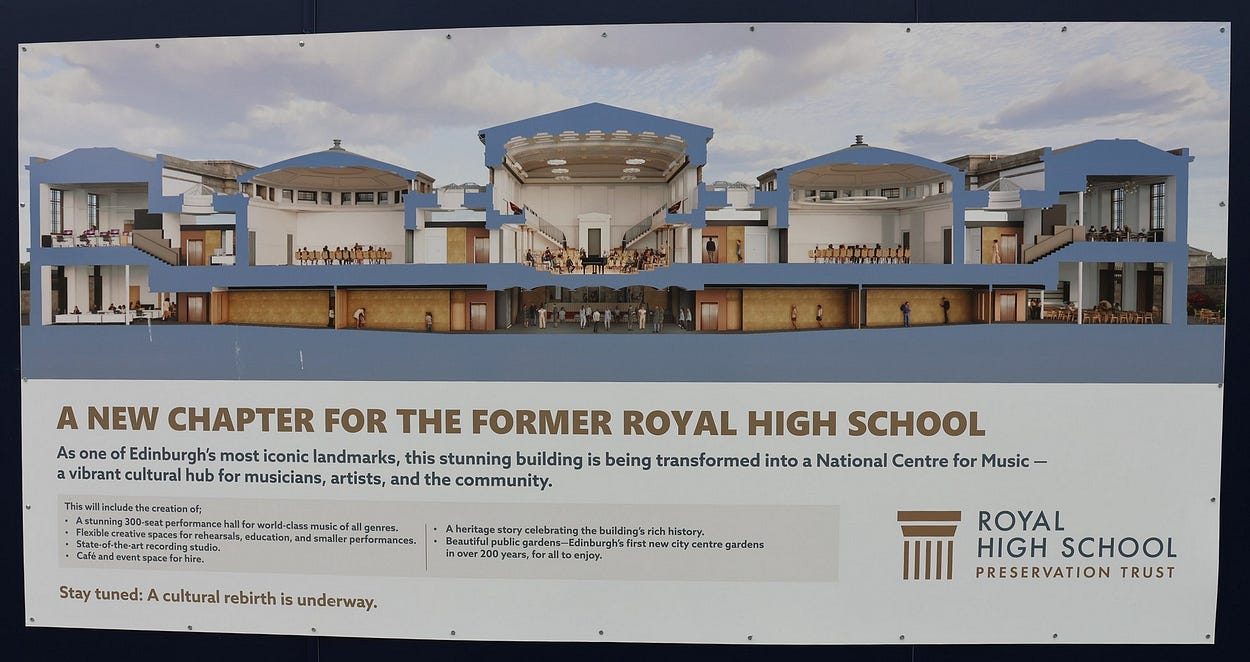

The Former or Old Royal High School, as this set of buildings is called today, is being remodelled into a music academy.

Other landmarks of Calton Hill include a never-finished monument to the victors of the Battle of Waterloo, the National Monument of Scotland, which was supposed to look like the Parthenon when completed, but ended up looking like a piece of conceptual art instead.

And the City Observatory.

And, the tower-like Nelson Monument, which offers even better views over the city and over the rest of Calton Hill.

The tower has a spiral staircase with 143 steps and an observation deck, but you can’t go up if the weather is bad.

At the top, there is a time ball, which you can just see in the photograph above, below the cross-like flagpole. The time ball is hoisted up the flagpole as 1 pm approaches and then dropped on the dot of 1 pm, at the same time as a big gun is fired at Edinburgh Castle. The castle gun is big enough to be heard all over town, and can give you a bit of a start if you are near Edinburgh Castle and don’t know about it.

Here’s a recent video of the firing of the one o’clock gun at Edinburgh Castle, by the way. It is all done with military precision and taken very seriously indeed, to the point that there are two guns in case the first one doesn’t go off properly.

In the 1800s, and on into the early twentieth century, time balls and time guns helped sailors to reset their chronometers, highly accurate clocks used for calculating longitude at sea. The time ball served as a visual time signal, and the gun as an acoustic one in case the time ball was hidden by fog.

Of course, we now have time pips on the radio, and, in any case, GPS is the main instrument of navigation. But Edinburgh carries on the old traditions, for old times’ sake.

Returning to Calton Hill, here is a view of the City Observatory and the Firth of Forth from the top of the Nelson Monument, on a somewhat finer day.

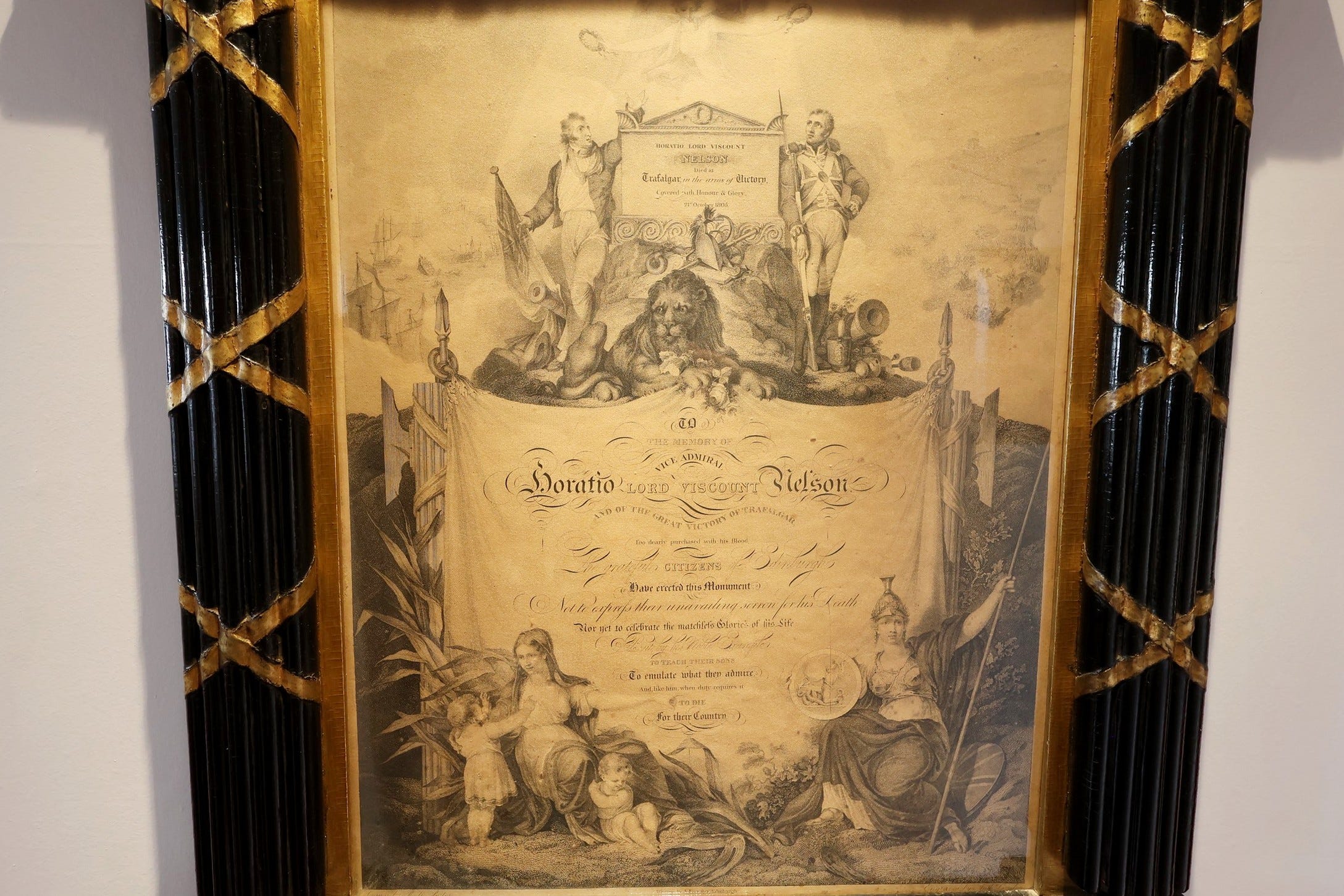

The Nelson Monument has a military and scientific museum at its base, which is also well worth checking out. It honours Nelson, of course:

And, Charles Piazzi Smyth, Astronomer Royal for Scotland from 1846 to 1888, who noted the poor observing conditions on the top of Calton Hill and lobbied for observatories to be erected in truly remote locations where the visibility was better.

Charles Piazzi Smyth also championed the installation of the time-ball on the Nelson Monument at Calton Hill.

The great hill, or mountain, of Arthur’s Seat is only a short distance from Calton Hill. Here is an old engraving of the ‘North Prospect,’ or view from the north, of the City of Edinburgh, which shows the city with the castle at the right and Arthur’s Seat at the left.

The engraving is dedicated to Queen Anne, the last of the Scottish Stuart dynasty, who reigned over Great Britain and Ireland in the heyday of the real-life pirates of the Caribbean, and after whom the legendary real-life pirate ship Queen Anne’s Revenge was named.

Arthur’s Seat is the main feature of Holyrood Park, a park both bigger and wilder than the Princes Street Gardens.

Here is a video, which I also put up last week, of my rambles through Edinburgh Castle, the Royal Mile, up Arthur’s Seat, and in front of the Palace of Holyroodhouse.

Hiking back into town from this end, you can also pass through the New Calton Burial Ground and then the Old Calton Burial Ground. Even these graveyards are rather hilly themselves and afford their occupants a good view, or would do if they were still alive.

The next photo shows the tomb of someone who might have been taken for a journalist but who was in fact a lawyer, a member of the Society of Writers to His Majesty’s Signet as they were called.

I did think it was a bit grand for the proverbial ‘ink-stained wretch.’ Not sure who Doctor Jefferiss was, whether he helped pay for the tomb, or was belatedly added, or what.

And here’s one that serves to remind us that the occupant is dead.

The adjacent Old Calton Burial Ground includes political monuments, such as one that honours Abraham Lincoln and Scottish soldiers who fought for the Union in the American Civil War.

And a huge obelisk called the Political Martyrs’ Monument, erected in honour of five individuals who were transported to Australia for the crime of advocating universal suffrage and annual parliaments in the 1790s. They were tossed into the hold of a ship along with other future Australians who had just barely escaped being hung for stealing sheep, and so on. Makes you realise how times have changed.

This post was completed with the help of new photographs and observations by my friend Chris, as well as content from an earlier blog post of mine, now superseded. I may catch up with my promised story about the mine at Tarras next week; otherwise, Chris will do a story of his own about Edinburgh.

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive free giveaways!