AS I mentioned last week, Potsdam sits in a watery landscape. On one of the streets, I saw this orientation map, which provides a wonderful overview of the land and the water, and of how much of it is quite green as well.

I started off my second full day of explorations in the dead centre of town once more, the area defined by the Garnisonkirche and film museum.

And on the other side of the street by the approaches to the Alter Markt, Friendship Island, and the Hauptbahnhof.

I decided to make a proper exploration of the Friendship Island, not far away as you can see from this shot, which includes the dome of St Nikolai.

On the side facing St Nikolai, the island has a cafe and museum buildings. The sign in the next photo says ‘BOAT LANDING STAGE / Angling forbidden!’ There were quite a few people angling on the built-up embankment on the far side.

The other side faces a much more natural branch of the River Havel.

And there was no shortage of Communist-era statues, that being the time when, as it seems, the island was made into a park. I quite liked this one, ‘Tanzpaar,’ or Dance Pair, dating back to 1962.

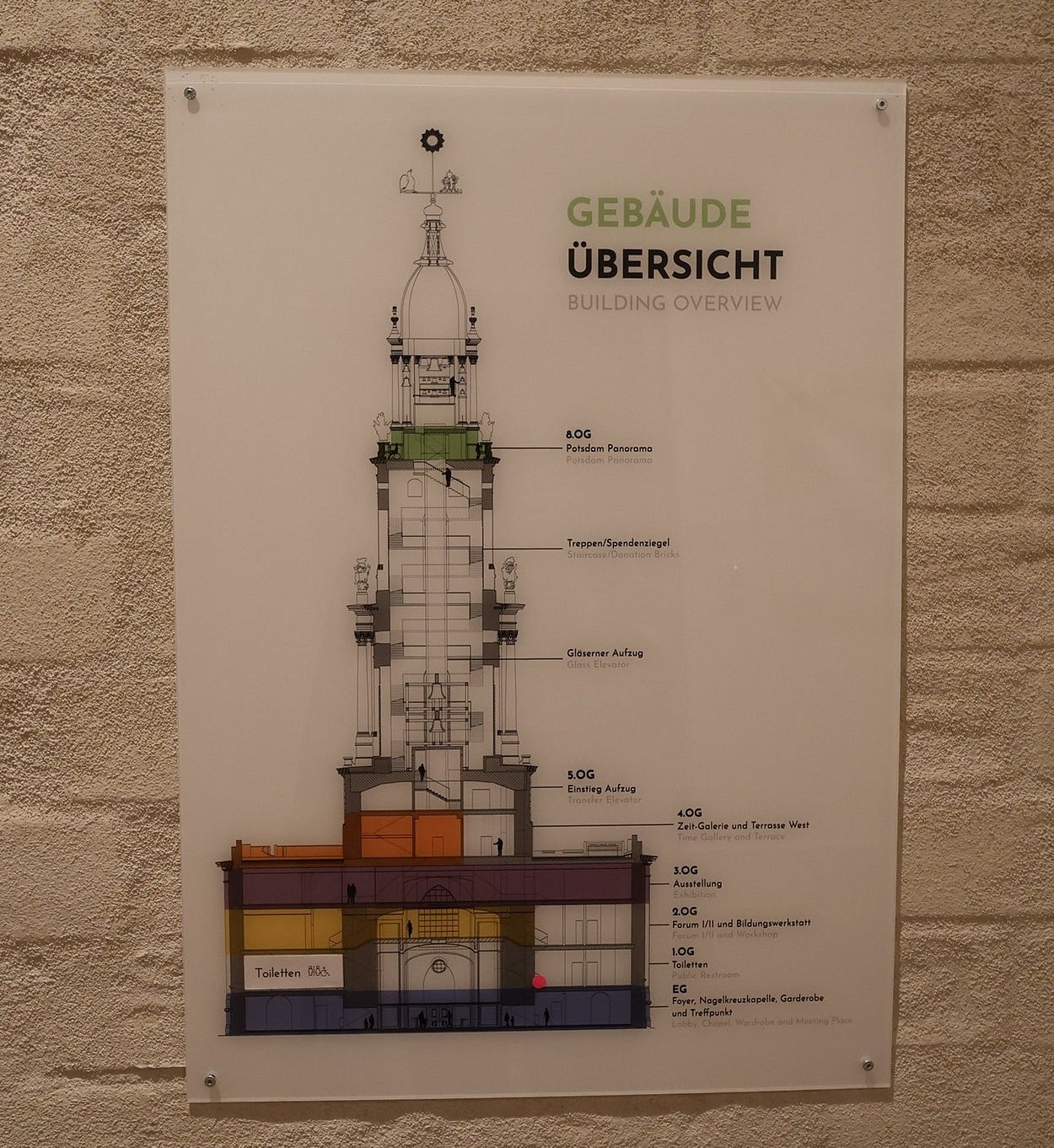

After Friendship Island, I decided that I had to explore the Garnisonkirche and its Panorama Deck, 57 metres above the street.

On the way from Friendship Island to Breite Strasse, the street where the Garnisonkirche is, I heard an alarming civil defence test, with sirens and phone alert, which reminded me that the war in Ukraine wasn’t really that far away.

On Breite Strasse, I noticed that the glass mosaic murals on the Rechenzentrum (computer centre), created when this part of the country was known as East Germany, and the caged Garnisonkirche weathervane outside, both looked a lot better now that the sun was out.

It turned out that the rebuilt tower had a museum inside, and that you could get to the Panorama Deck by a modern lift, a definite improvement over the 365 steps to the top of the old tower, doubtless up some terrifying spiral staircase (though, for the modern enthusiast, the rebuilt tower has a staircase as well).

Built in the early 1700s, the original tower of the Garnisonkirche was the highest building in Potsdam at the time.

Before heading to the Panorama Deck, I checked out the museum, which mostly dwelt on the church’s historic connection with the Prussian state and its military traditions, as well as the controversy attending its reconstruction.

As I also mentioned last week, the original Garnisonkirche was blown up by the Communists in 1968 to make way for the Rechenzentrum: an action that was also quite controversial, the subject of about as much of the limited amount of protest allowed in the former East Germany in those days, given that the tower was of great historical and architectural significance even if it was strongly associated with the old Prussian and German regimes.

The next photo shows an old painting of the Garnisonkirche next to an image of Prussia’s most famous king, Frederick II (‘the Great’), who reigned from 1740 to 1786. It quotes the young Frederick, in 1740, as saying ‘Wage war, fight battles, overrun or defend fortresses, is the one and only thing for great princes.’ Frederick would wage several wars that ended up with the enlargement of Prussia, which his regime viewed as a champion of the Protestant religion, at the expense of several neighbours, above all Catholic Austria, from which Prussia obtained the province of Silesia, famous for its ironworks and coal mines.

After he had won his wars, which possibly had more to do with iron and coal than religion, Frederick settled down and became a more cultured sort of monarch, and even built a Catholic cathedral in Berlin, St Hedwig’s, after the patron saint of Silesia, to show that there were no hard feelings.

Next week, I’m going to explore Frederick’s fabulous palace and gardens of Sanssouci. So, again, that’s something to look forward to!

Frederick, his father Frederick William I (known as the Soldier King) and his successor Frederick William II, who died in 1797, were all rather aloof and autocratic.

Famously, Frederick II spoke French at court, admitting that he spoke the German language “like a coachman” but that this did not matter because he only used it to give orders to his horses! This was a routine aristocratic attitude at the time, the ruling classes speaking French from Paris all the way to Moscow, pretty much regardless of whatever dialects the peasants and townsfolk spoke.

However, come the French Revolution, it became clear that the times called for rather more of the common touch. The old powdered-wig fashions fell by the wayside, and people began to dress in much more of the way that they do now.

The same went for royal aloofness. One of the first to adopt a new approach was the wife of the Prussian King Frederick William III, who gained the throne in 1797, Queen Luise.

Queen Luise cemented her popularity with the common folk of Prussia by dressing plainly by eighteenth-century standards and, in one celebrated incident, picking up and kissing the child of a commoner, the original act of ‘baby kissing’ and pretty much unheard of at the time.

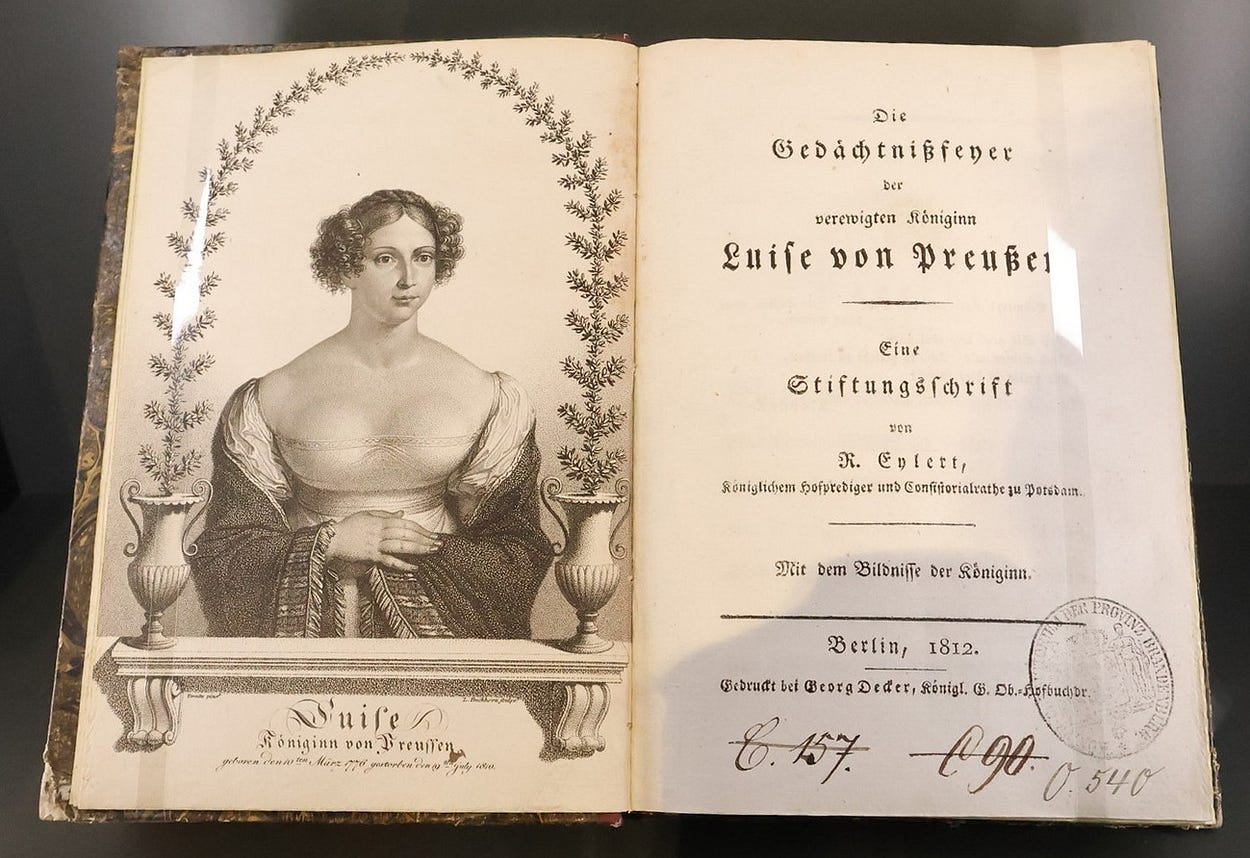

In many ways, Queen Luise was the original Lady Di. And in another parallel, she secured the nation’s grief and a sort of iconic status by dying prematurely, while she still looked fabulous, in 1810. The museum displayed a book of memories published in 1812, in German (whatever Frederick II might have thought of that).

Even a hundred years later, or nearly so, the life of Luise would be celebrated in a book called Louise, Queen of Prussia.

Although Frederick William III was quite non-militaristic by the standards of his fearsome forbears, and had looked forward to a peaceful reign, he wasn’t long on the throne before Prussia was dragged into the Napoleonic Wars, in ways that involved several battles and a heavy defeat in 1807.

Following the defeat of 1807, Prussia’s capital, Berlin, was triumphally occupied by Napoleon. In the same year, Queen Luise visited Napoleon to try and get him not to be too hard on the Prussians. When word of this got out, she became even more popular.

Despite their social position, the Prussian royals would face some genuine hardships over the next few years, living in filthy and freezing conditions in the provinces and constantly on the road, in ways that probably contributed to Luise’s early death, from what appears to have been pneumonia. Her husband survived until 1840 and thus lived to see Napoleon’s defeat at the so-called Battle of Nations in 1813 and, finally, at Waterloo.

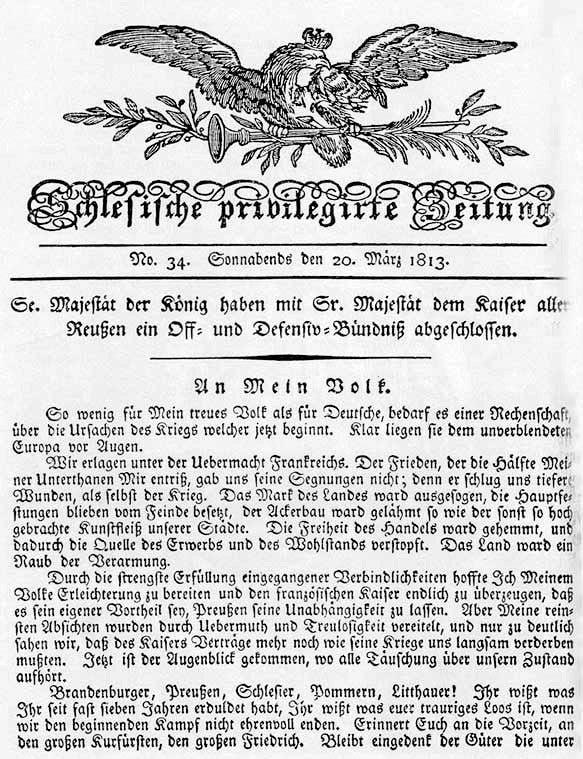

Shedding the last vestiges of the older aloofness, Frederick William appealed to the whole nation to rise up and kick out the French in an 1813 broadsheet called ‘An Mein Volk,’ meaning ‘To My People.’ It was written in German, the language of the commoners that Frederick II had disdained.

(You can find a historical explanation and translation in English, here.)

The museum also contained gory relics of a couple of the battles of that era.

From the Middle Ages until 1806, when it was abolished by Napoleon, most of Germany had belonged to a confederation known as the Holy Roman Empire (‘neither holy, nor Roman, nor an Empire’ as the French satirist Voltaire quipped.) This confederation was also known, later, as the First Reich, or in other words, the First (German) Empire, though it also contained most of the territory of today’s Czech Republic and parts of Italy.

While earlier royals had spoken French at court, the effect of Napoleon’s wars and invasions was to trigger a new sense of German nationality, now largely defined in terms of opposition to all things French and somewhat more focused on being German than in the days of the Holy Roman Empire.

And so, in 1870, a second and more explicitly German Empire was founded, following the defeat of the French in the Franco-Prussian War, in which most of the German states had taken part on Prussia’s side. By this stage, Prussia was the largest German state, and Wilhelm I, the King of Prussia, was proclaimed the Kaiser, or Emperor, of the new Second Reich, or Kaiserreich, in 1871.

The museum displayed a cartoon from that era, ‘Germany’s Future,’ which suggested that the rest of Germany would now fall under a militaristic tyranny, a prediction that contained a large element of truth. The cartoon used the device of the spiky ‘Pickelhaube’ helmet, introduced by the Prussians in the 1840s, as a symbol of the coming regime.

For many years afterwards, indeed even under the irreligious Nazis, German soldiers would display the words ‘Gott mit uns’ (God with us) on their belt-buckles.

The following quote, above a late-1800s colonial map and depictions of colonial conflicts in which Germany was getting involved by that stage, says that ‘The army [is] the great pulse-artery of the nation:’ the sort of praise that was heaped on the German Army in the days of the Second Reich. Actually, strictly speaking, there was no German Army as such back then, for the various German states continued to maintain their own armies, a gesture to former liberties. But they were all commanded by the Kaiser.

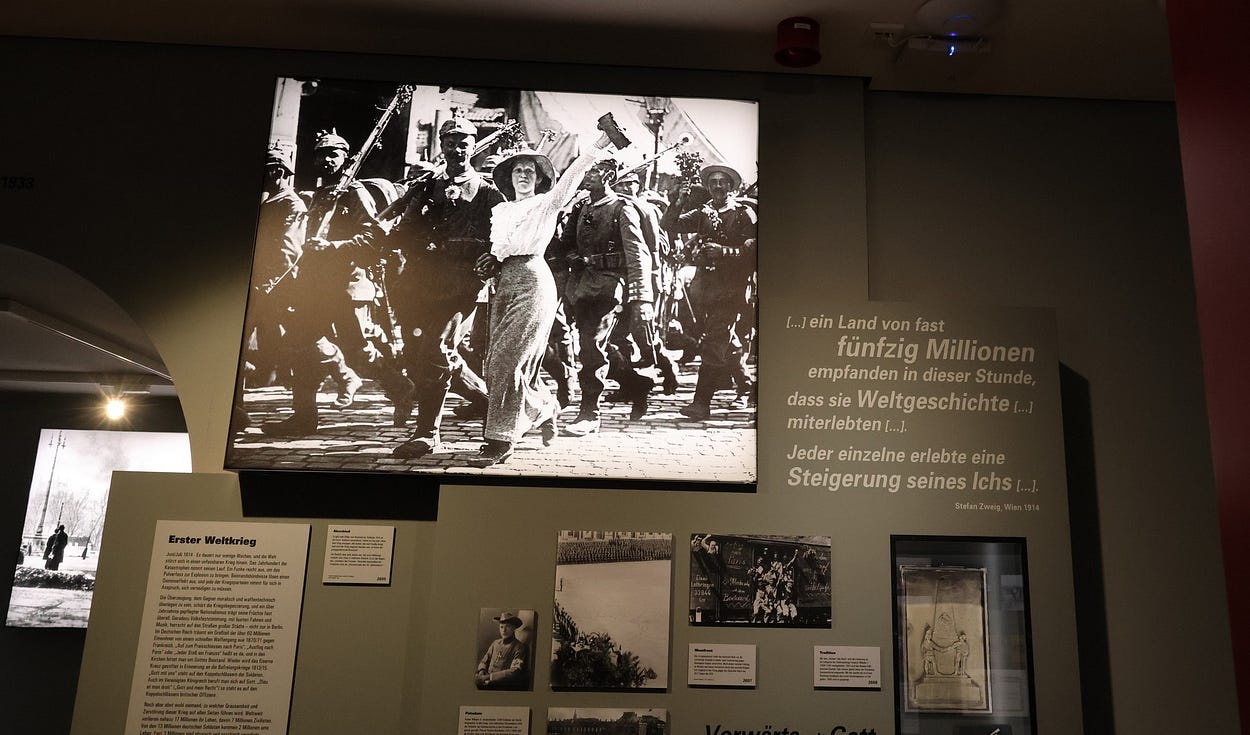

And then, of course, the country blundered into World War One.

And started World War II, under the Third Reich of the Nazis.

After which, there wasn’t a heck of a lot left of Potsdam, even if a few of the larger historic buildings were still standing, sort of. In the next photo, you can see the unmistakable bulk of St Nikolai even in the absence of most of its dome, and, in the background, what looks like the old tower of the Garnisonkirche, minus its steeple and weathervane and thus flat-topped like the tower of 2025.

It was amid these ruins that the famous Potsdam Conference of the victorious powers was held in 1945.

A lot of reconstruction happened under the Communists, who ruled eastern Germany thereafter until 1989; but they did blow up the old Garnisonkirche, and demolished the City Palace as well.

In the next photo, the caption on the Communist-era poster with two people on it says ‘All efforts for the building-up of socialism,’ while the one to its right, also from the Communist era, says ‘Everyone help with the reconstruction of Potsdam.’

I don’t know if any controversy attended the rebuilding of the City Palace. But with all this history, the rebuilding of the Garnisonkirche, a name that means ‘Garrison Church,’ certainly was quite controversial, and had to be put to a referendum. The museum has a section on that controversy as well. The following poster, with its caption ‘Stage Prop,’ suggested that only Nazis would want to rebuild the tower for old times’ sake.

Another suggested that the idea be blasted off into space.

But in any case, it is here now, and with that thought in mind, I made my way up to the 57-metre-high Panorama Deck to look out over the glorious historical, watery, and park-like townscape of Potsdam.

Here is a panorama video, from the Panorama Deck:

After coming down from the tower, I then made my way to Potsdam’s most important town square after the Alter Markt.

Namely, the Luisenplatz, named after Queen Luise (naturally).

The following information panel in the Luisenplatz shows its location, marked with a big red dot. There is a QR code, with a link to potsdamtourismus.de.

The following two photos show the Brandenburg Gate in Potsdam, which has the same name as the more famous Brandenburg Gate in Berlin, and is actually older. Such gates really were gates: they used to form openings in old-time city walls, long since torn down. The side you can see in these photos is the outer side, done in a different style to the inner side.

Potsdam has three city-wall gates still standing: the Brandenburg Gate in Potsdam, the Nauen Gate, and the Jägertor, which means hunters’ gate, because it is decorated with hunting scenes.

A detailed page about the heritage buildings and public spaces on Potsdam.de, called ‘Between the Brandenburg and Nauen Gates,’ states that the Luisenplatz used to be a car park!

The car park was eventually abolished in the nineties, or at the time of the millennium, when an underground parking garage was built to replace the car park on top.

Very little space seems to be given over to surface-level carparks in downtown Potsdam today, even if it used to be in the past.

English-speaking cities could do the same: it is all just a question of how much we value parks for people as opposed to parks for cars.

Here is a pan around the Luisenplatz:

However, the real significance of the Luisenplatz is that from there it’s just a short walk, 300 metres, to the real jewel in Potsdam’s crown, the vast, UNESCO World Heritage Park Sanssouci, which contains no less than four palace complexes — the original Sanssouci, the Charlottenhof Palace, the Neues Palais (New Palace) and the Orangerie Palace — and a host of other heritage buildings, all in a vast area of landscaped grounds.

It is to Park Sanssouci that I will be heading next week, down the 300-metre Allee nach Sanssouci, and beyond.

Till next time!

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive free giveaways!