AFTER the Duxford air show, I flew from Stansted Airport to the new Berlin Brandenburg airport, southeast of Berlin, and from there caught a westward-bound regional train to Potsdam.

Potsdam is about 30 km from the heart of Berlin. It lies in a lovely area of lakes and forests which make it a bit like a seaside resort, even though it is inland. The people there are really into boating. I stayed at a place called Glamping-Ei on the Yachthafen Potsdam, the main yacht marina.

Potsdam bills itself as the ‘City of Sans, Souci,’ after the famous royal palace of Frederick II of Prussia, also known as Frederick the Great, shown as Schloss Sanssouci in the map above. I visited Sanssouci, and I’ll be blogging about that and a whole lot of other sights next week.

But the first day I was there, I just walked about, gradually orienting myself. I didn’t actually know too much about the place other than that it was the location of Sanssouci, and so there was a surprise around every corner.

The first thing I noticed was that everything seemed to be rather grand, with statues on top, such as the Commerzbank on Lindenstrasse.

And the gilded cupola on top of the regional government buildings further down the street.

A lot of the older houses and apartments were highly decorated with statues and reliefs.

.

(I actually took the next one in the nearby city of Brandenburg an der Havel, but it is the same idea.)

In the middle of town, there’s the Filmmuseum Potsdam. The heart of the old-time German film industry lay in Babelsberg, the easternmost suburb of Potsdam, and there are lots of historic film-making studios to see in Babelsberg as well.

The city is well served by local tramways, which converge on the main Potsdam railway station, or Hauptbahnhof, close to the film museum.

There’s a shopping mall and gym complex that’s built into the Hauptbahnhof, called Bahnhofspassagen. Above the main entrance to the Bahnhofspassagen, in the next photo, the red-on-white DB stands for Deutsche Bahn, or German Railways, meaning the inter-city trains, while the white on green S stands for Berlin suburban trains.

As in much of Europe, you don’t need a car to get around. Check out all the bikes!

Here’s another photo from outside the film museum, showing ads for city tours and hop on-hop off buses. On the left, there is a wide street called Breite Strasse, which literally means ‘Broad Street,’ and in the background there’s the pinkish, lately-rebuilt tower of the Garnisonkirche, or Garrison Church.

The Garnisonkirche tower doesn’t look very big in the photo above. Actually, as you can see from the next photo of a woman walking toward it on Breite Strasse, it’s colossal.

I came back when the weather was better and rode a lift to the top of the Garnisonkirche tower to look out over the city from the top, and I will show you some photos and video that I took from the top in the next post. That’s something to look forward to!

Potsdam used to be part of the former East Germany. The Communists blew up the original Garnisonkirche in 1968, because of its associations with the old-time Prussian and German armies, of which it was the principal site of worship and religious ceremonies. The site was cleared for the construction of a new building called the Rechenzentrum, or computer centre, which the present regime has somehow managed to preserve even while rebuilding the Garnisonkirche tower.

The Rechenzentrum has a glass-tile mosaic around most of its base, called Der Mensch bezwingt den Kosmos, meaning ‘Humanity conquers the cosmos.’ Like Mexico, the former East Germany abounded in inspiring murals, and Der Mensch bezwingt den Kosmos was — is — a fairly typical example.

In front of the mural, on Breite Strasse, there’s currently a cage in which the reconstructed old-time weathervane, due to go back on top of the steeple of the Garnisonkirche as the final touch to its restoration, is currently being stored. It makes an interesting contrast with the mural behind.

A picture of what everything is going to look like when the job is finished, with the Rechenzentrum building demolished but the mural remaining, can be seen here.

There are in fact a great many reminders of the Communist era, including such street names as Friedrich-Engels-Strasse, one of the three streets that the Hauptbahnhof spans.

And the jaunty Ampelmännchen, or little traffic light man, the East German design for pedestrian crossing signals, which has been retained to this day and is basically an icon of the former East Germany.

And a certain amount of public art from the Communist era as well, such as this work from the 1970s, Transparente Weltkugel or Transparent World-Ball, listing the names of famous philosophers including, to the left, Marx, in front of some brightly coloured apartments.

Between the film museum and the Hauptbahnhof there is an island in the local river, the Havel, called the Freundschaftsinsel, or Friendship Island. This is quite a pleasant park, which also sports a lot of Communist-era public art, such as the reclining bronze figures to the left in the next photo.

However, the most amazing discovery I made on my first day was the Alter Markt, or Old Market, which is also in the vicinity of the film museum, the Hauptbahnhof, and Friendship Island.

There are several ways into the Alter Markt, such as Humboldtstrasse, below. But you can always tell whether you are headed in the right direction because the colossal dome of the Church of St Nikolai can be seen all over downtown.

Though Potsdam is 30 km from the centre of Berlin, even so, the dome of St Nikolai is just a few metres shorter than the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral in the heart of London.

At the end of Humboltstrasse, which is just a short street, you can see the Alter Markt and another of its iconic buildings, the old town hall, with a gilded figure of Atlas holding up the world on top. This is another real icon of Potsdam.

The red building to the left of both photos is the Potsdam City Palace, also demolished by the Communists only to be reconstructed in the 21st century, and which is also the site of the Landtag of Brandenburg, or in other words, the parliament of the German Federal State of Brandenburg.

The sign on the City Palace is bilingual. I thought the second language was Polish at first, since Sejm is Polish for parliament. But it turns out that it is Lower Sorbian, a local community language similar to Polish but not the same.

Lower Sorbian is one of the dialects of a group of people called the Sorbs, or Wends, who are the indigenous inhabitants of the eastern part of today’s Germany.

Unlike the Poles, the Sorbs never had their own country. They went straight from a tribal existence, like that of the Scottish clans or Māori iwi in the time of Captain Cook, to being incorporated as a minority into German-speaking kingdoms that expanded eastward across the Elbe River from the original homeland of the Germans, which lies to the west.

Even Berlin was originally a Sorbian village. Though its flag features a bear, since Berlin sounds like ‘Place of the Bear’ to a German ear, the name Berlin is really thought to come from a Sorbian phrase meaning ‘Swampy Place.’

German real estate entrepreneurs probably did their best to get everyone to forget the ‘Swampy Place’ story, even as they drained the actual swamps.

As you can see from the map at the start of this post, the Berlin region is full of rivers and lakes, even today. There would have been more of them in the past, as the German colonisers did indeed drain many of the marshy bits, which for the Sorbians were a good source of eels and an impediment to their enemies, to establish dairy farms and new villages.

The fact that several main roads in Berlin have names that end in -damm dates back to those times, since, in German, ‘damm’ means dam, stop bank, or dike. Whence, also, the names of entire cities such as Amsterdam and Rotterdam in the Netherlands.

The name of Potsdam isn’t thought to refer to any dam or dike, however, but rather to come from the Sorbian expression Potztupimi, meaning ‘under the oaks;’ a name to which hardly anyone could object.

Anyhow, getting back to the Alter Markt, the City Palace is truly impressive, just like the rest of the buildings there. Here is a view of St Nikolai from inside the courtyard of the Landtag.

The City Palace was covered in old Prussian crests and other decorative features. The photo that follows is quite interesting, as it shows a contrast of bits that have been cleaned of centuries of grime and possibly from World War II smoke damage as well, and bits that haven’t yet, such as the head of the female figure to the left.

There was a collection box (‘Spendenbox’) in the City Palace courtyard, for funds to restore the old statues and decorations.

Even some of the columns on the City Palace itself looked a bit knocked about, still.

There was on exhibition on at the time, called Potsdam in Farbe, meaning Potsdam in Colour, organised by the Potsdam Museum. which is also in the Alter Markt.

It was amazing to see how much the place has obviously been patched up since the early postwar days.

I went inside St Nikolai, and up to its viewing platform, which isn’t as high as the Garnisonkirche one but does offer different perspectives.

Photography doesn’t really do justice to the church interior, of course.

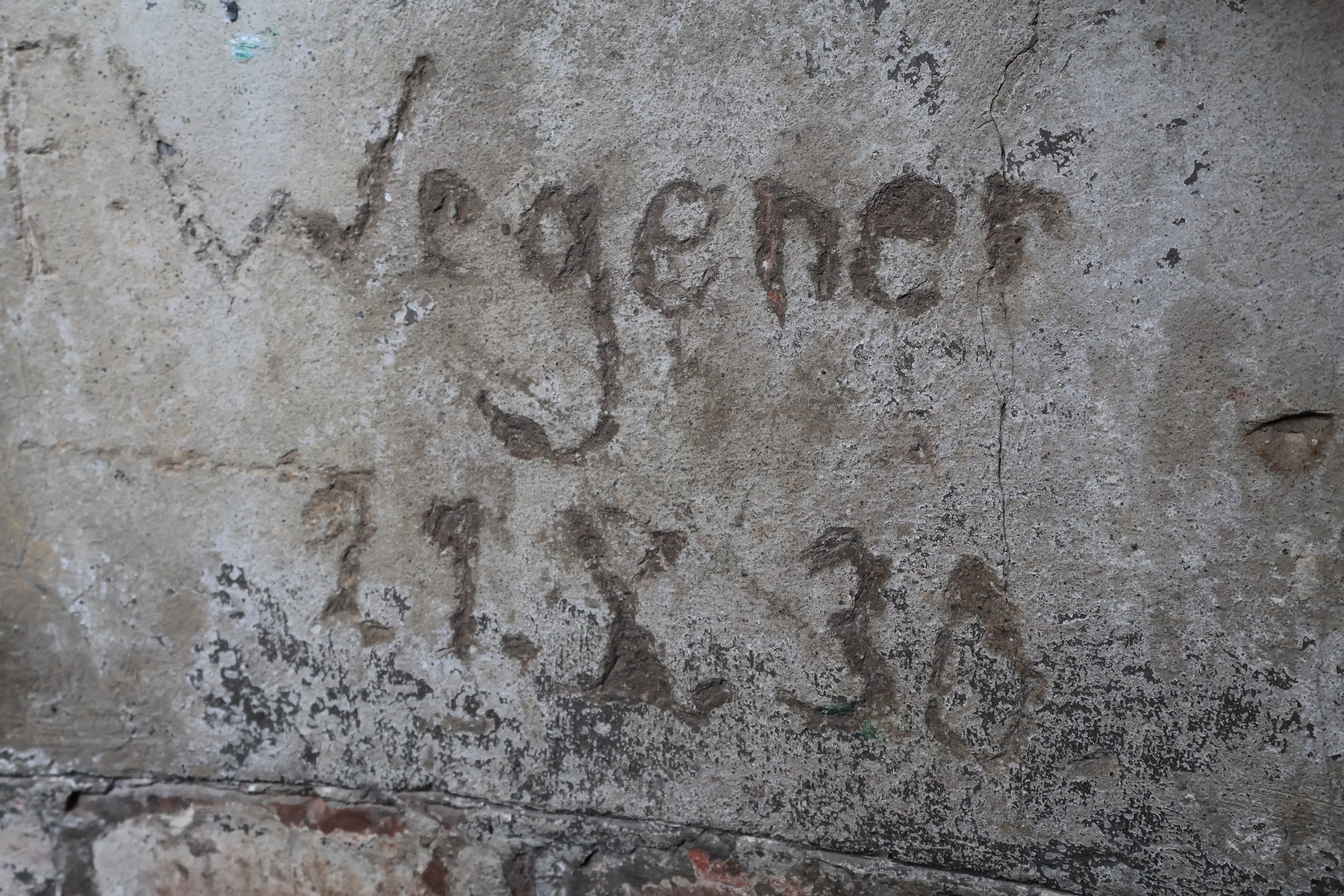

Was this 1930? Or 1830?

Finally, here is a pan around the Alter Markt.

Next week, I will continue my tour of Potsdam. But in the meantime, here are a couple of useful tourism websites for this area, Potsdam-tourism and Berlinstaiga.

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive free giveaways!