FOLLOWING on from last week’s Part One, this post shows a few more photos and videos of the military airshow, before I (Chris) go on to take a look at a proud lineup of British airliners, and ask why there aren’t any more these days.

Here’s one of the P-51 Mustangs that took to the air that weekend, a handsome machine.

And the Hawker Fury:

Here’s a video of the B-17 G ‘Sally B,’ which was built in 1945, taking off, in flight, and landing, along with other aircraft movements. In order, those are a Spitfire Mk XIV landing, a taxiing Bristol Blenheim, the Hawker Fury that I photographed above taking off, and a P-47 Thunderbolt taking off.

And a similarly atmospheric photo of a Douglas A-26C Invader, ‘Sweet Eloise II,’ which was also built in 1945. This aircraft flew really fast and would attack ground targets by surprise: the latter A stood for ‘Attacker.’

There was an American Catalina flying boat, built in 1943. The Catalina was used for patrols and also for rescuing people from the sea. Needless to say, this one was called Miss Pick Up.

A really distinctive feature of the Catalina is its ‘blister’ windows, halfway toward the tail, which are made of blown plastic, a very new thing when it was first built.

On Miss Pick Up, the blister windows are tinted the colour of sunglasses, so they look black in the photo. But you can definitely see out from the inside.

You could go inside the Catalina and peer out through the blister windows, which offered the most fantastic view.

There was a sign saying that the blisters must not be opened in flight, just in case anyone was silly enough to do so.

Here’s a video of Miss Pick Up and a Fairey Swordfish torpedo bomber. The Fairey Swordfish was the famous torpedo bomber that helped to sink the Bismarck in 1941 and also much of the Italian fleet at Taranto in 1940. The Swordfish flying here is a Mark 1 type built in 1941, and is the oldest flying Swordfish in the world.

There was a full-motion simulator in which you could pretend to be in the cockpit of a Battle of Britain fighter plane. Despite all the patriotic imagery on the outside, it turned out to be a Messerschmitt on the inside.

And so we come to the civilian airliners, the British Airliner Collection, maintained by a charity called the Duxford Aviation Society.

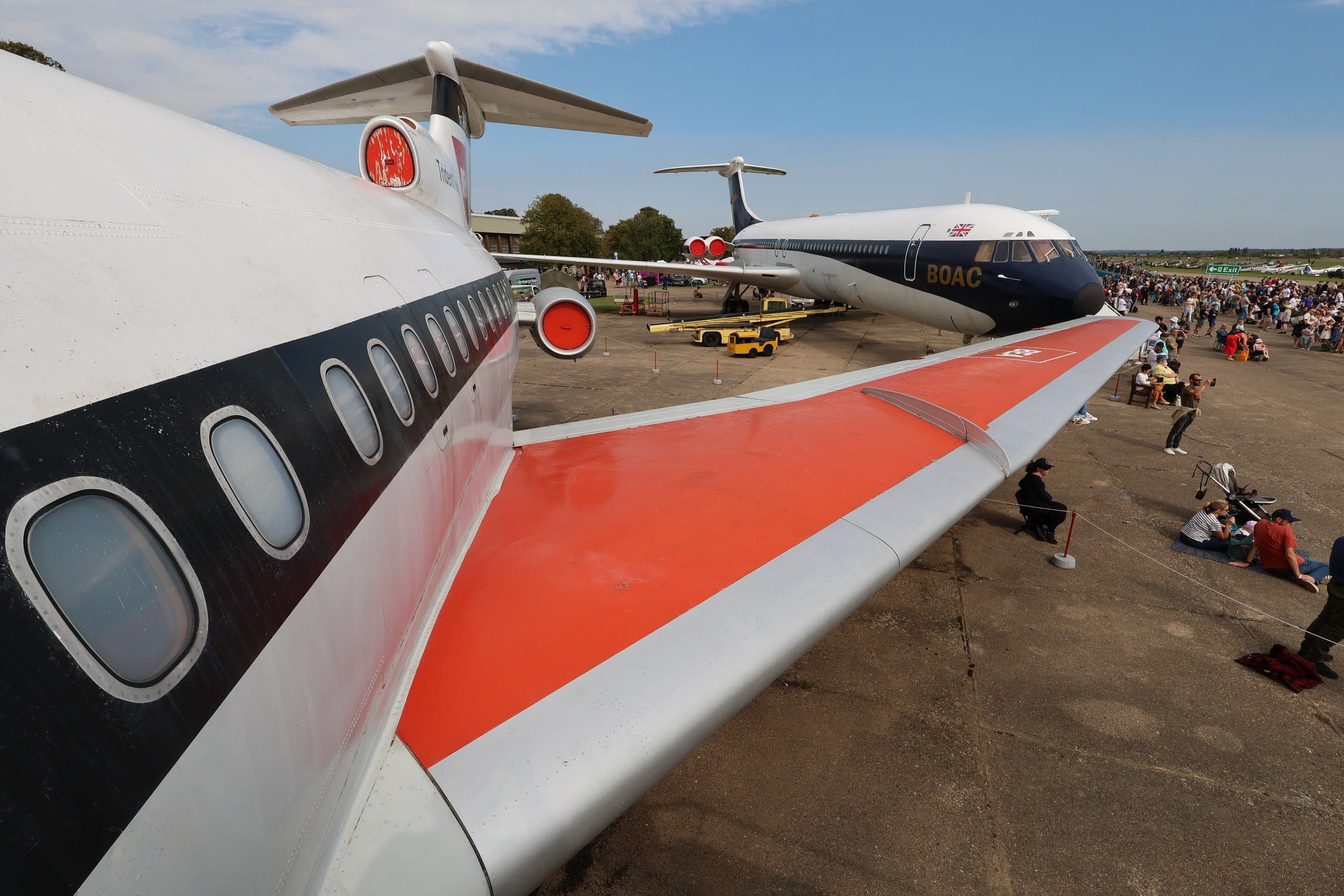

Here are several of the airliners in a row, from the left a BAC 1–11, which has two engines in the tail, a Hawker Siddeley Trident, which has three, and a Vickers Super VC-10, which has four. And then a de Havilland Comet 4, a Bristol Britannia turboprop, and a Vickers Viscount turboprop, the world’s first turboprop airliner.

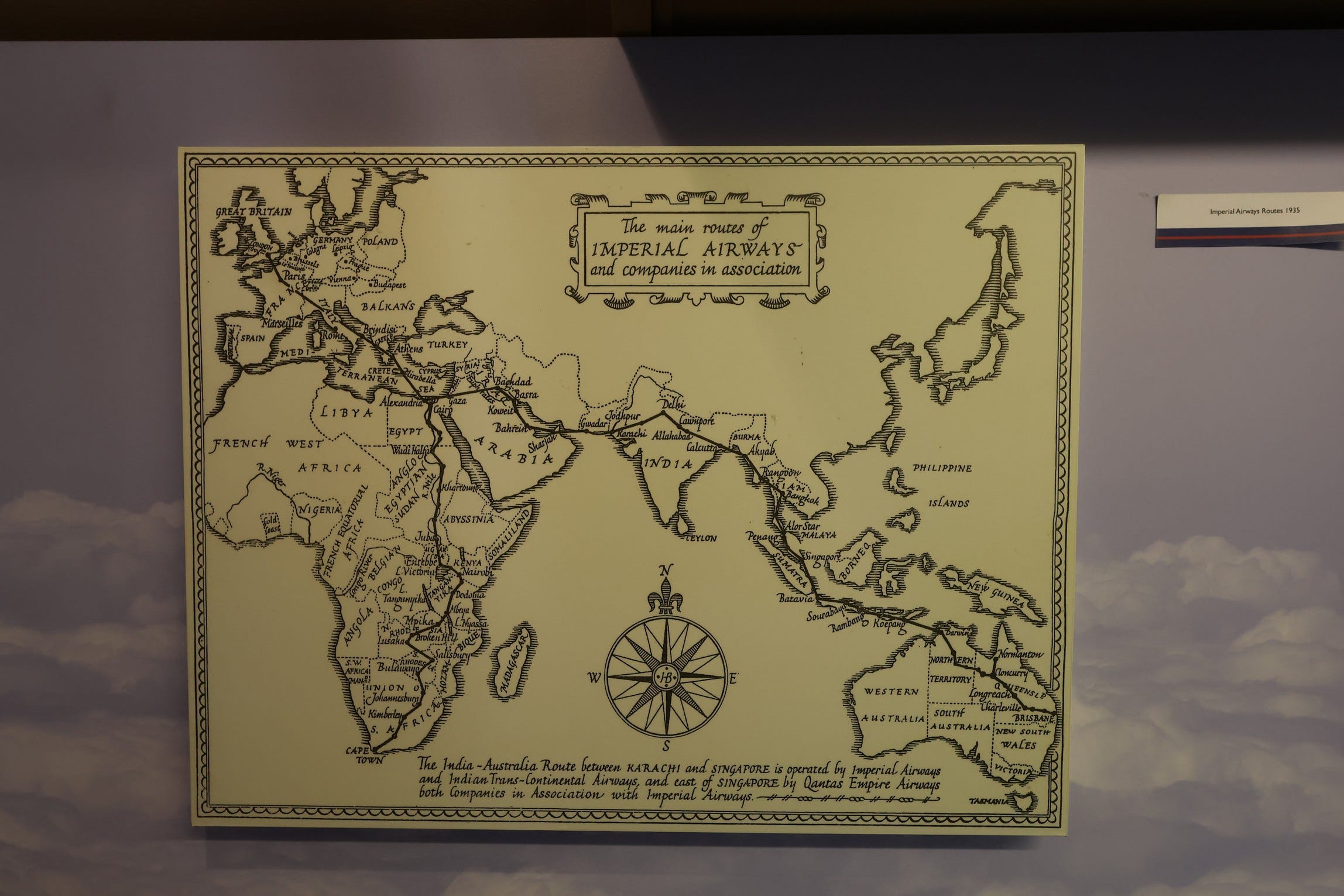

The decline of the British airliner industry is quite remarkable, given that Britain used to make a great many airliner types. It all started, of course, with the development of airliners to serve the once-vast British Empire.

It doesn’t look as though Imperial Airways made it all the way to New Zealand, which was served in those days by Tasman Empire Airways Limited, or TEAL, a forerunner of Air New Zealand. Nor Canada, as it would seem.

The collection at Duxford includes the Anglo-French Concorde, at the left of the following photo. You can go inside all these airliners, incidentally.

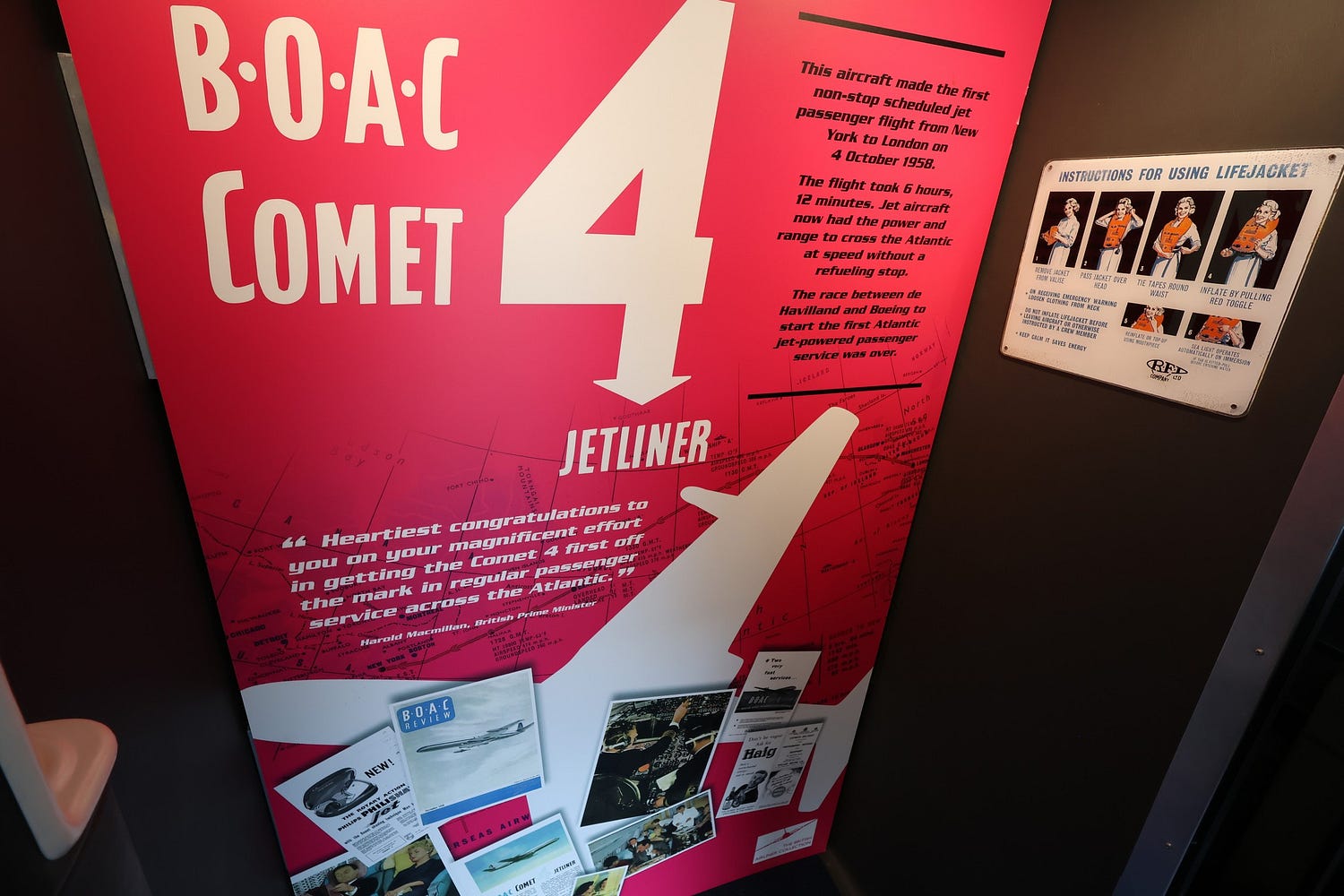

The first jet airliner to enter service in a big way was the de Havilland Comet, which first flew in 1949 and made its commercial debut in 1952. After some accidents, it was redesigned and put back into service as the Comet 4 in the late 1950s, though by that stage it faced serious competition from two new American airliners, the Boeing 707 and Douglas DC-8.

Here’s the Comet 4 at Duxford. The engines are in the wing roots, which was an elegant configuration but also made it impossible to install later, more efficient types of jet engine, which tend to be wider.

The in-flight food and drink on the Comet 4 were rather magnificent. Of course, in those days, flying was more expensive than now. The very cheapest seats you could purchase back then were the equivalent of business class today.

Here’s a view of the Super VC-10 from the Trident (the Super VC-10 was the stretched version of the original VC-10).

Along with the BAC 1–11, these rather glamorous-looking aircraft, known for obvious reasons as T-Tails, all entered service in the mid-1960s. Here’s another shot of the Super VC-10, the most glamorous T-Tail of them all.

And of its massive, bird-like T-Tail, with the logo of BOAC, the British Overseas Airways Corporation, a successor to the pre-World War II Imperial Airways and a forerunner of today’s British Airways.

The nice thing about the T-Tails was that none of the jet-blast from the engines went past the windows, with the result that even the economy sections of the cabin had about the same noise levels as first class and business class, which are always at the front. The ‘clean’ wings, with no engines dangling off them, also performed better in turbulent air.

As of the time of writing, a page on the website VC10.net notes that:

[BOAC] quickly realized that the passengers loved the VC10. The rear engined layout made for a relatively quiet cabin and the efficient wings gave it a very smooth ride over turbulence. These qualities actually made passengers request the VC10 when given the choice, and BOAC used them to advantage when advertising with the phrases ‘Swift and silent’ and ‘A little VC10derness’.

To this day, business jets nearly always have their engines in the tail for those reasons.

But nearly all regular passenger jets now have the engines under the wings. This is mainly because having all the engines in the tail gets to be unwieldy if an airliner is very big.

The VC-10 was BOAC’s long-distance flagship in the 1960s, flying the Atlantic, to Southern Hemisphere destinations, and over the North Pole.

But with only one aisle and six-abreast seating in economy, the VC-10 would only be a mid-sized regional jet by the standards of today. It would be the equivalent of the Airbus A320, a jet that is commonly used for two-hour hops.

After the Boeing 747 ‘Jumbo Jet,’ with two aisles and ten-abreast seating in economy, set a new size standard for long-distance service at the start of the 1970s, having the engines under the wings like the Jumbo gradually became the standard even for smaller jets.

Still, many people think the rear-engine setup should have been retained on as many mid-sized jets as possible, rather than being allowed to slowly die out for all sizes of passenger jet. They also claim that, since the VC-10, nothing has ever looked quite as good!

Though the British once made many of the world’s airliners, including some of the best-looking ones, the British airliner industry gradually went under, just like the British car industry and the British motorbike industry, for reasons of stuffed-shirt mismanagement of a kind that makes you wonder how Britain ever rose to prominence in the first place. But that is another story!

Getting back to the military side of things, I saw some tents belonging to the famous Royal Air Force aerobatic team, the Red Arrows.

The American Air Museum, on the same site, also had many iconic American planes. In this view, you can see the U-2 spyplane above the wing of the museum’s B-52 bomber, with the nose of an SR-71 Blackbird at the left, next to a section of tube that was part of the Saddam Hussein-era ‘supergun’ developed for the Iraqis by the Canadian engineer Gerald Bull.

There were lots of food stands, including an extremely small and traditional-looking ice-cream van, which looks like some sort of a museum piece in itself.

I also made sure to get some souvenirs, including a fridge magnet reproduction of a poster aimed at munitions workers that said not to take alcoholic drinks on Mondays. Well, certainly not if you are screwing bombs together!

Finally, on the way between Duxford and Cambridge, there is a place called Trumpington where they have some houses with thatched roofs. I couldn’t resist getting some pictures of these quaint dwellings as well.

To conclude, there was heaps more at Duxford. One thing I entirely forgot to check out was the 1940 Operations Room, with its map plotting table and all the other detailed communications arrangements by which local fighter squadrons were coordinated. This level of coordination was a major contributor to Britain’s victory in the Battle of Britain, though somewhat ‘behind the scenes.’ Here is an IWM video about the operations rooms, with a special focus on Duxford’s one:

Next week, I head for Berlin and the nearby city of Potsdam.

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive free giveaways!