LAST WEEK, I mentioned how modern Napier began as a settlement on Scinde Island, known in Māori as Mataruahou, and a few adjacent sandbars, and was uplifted by the 1931 earthquake.

And how Mataruahou, or Scinde Island, is now known as Bluff Hill, given that it is no longer an island.

Actually, there are two hills on Mataruahou, to use its Māori name: Bluff Hill close to the shore, and Hospital Hill inland, where the old Napier Hospital was located. Hospital Hill also had significance for the old-time Māori as a healing place, interestingly enough. On Bluff Hill, there is the Clyde Road Lookout, likely the spot from which the following photo was taken.

On Hospital Hill, there are the Napier Botanical Gardens, and a colonial graveyard that includes the graves of Missionaries such as William Williams, the first translator of the Bible into Māori, and William Colenso (cousin of John Colenso after whom a town is named in South Africa), who printed the Māori text of the Treaty of Waitangi.

I think old cemeteries are amazing regardless of who’s buried in them, don’t you?

In the old days many Māori lived on Mataruahou, where at one location a stream descends down a cleft in a local cliff. In a local legend, a mermaid named Pania, who lived on an offshore reef, was drawn to this stream (which still exists) and fell in love with a chief’s son named Karitoki, who used to drink from the stream because it was the purest on the island. The two were secretly married, but Pania had to return to the sea for the duration of each day and could only be with Karitoki at night.

Pania could not continue to return to the sea if she ate cooked food on land. So, one night, Karitoki put cooked food in her mouth as she was sleeping in the hope that she would swallow it and thus stay with him all day. But just at that moment Pania was awakened by the warning cry of an owl and ran to the sea in horror, whereupon the sea-people dragged her down and she was never seen by Karitoki again.

A statue of Pania, generally known as ‘Pania of the Reef’, was unveiled in 1954. Here’s a photo taken in 1967 for New Zealand’s National Publicity Studios by Gregor Riethmaier.

And here’s me beside it!

Māori and other Polynesians are related to the majority populations of Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines as well as to certain minorities in Taiwan.

Collectively known in scientific parlance as Austronesians, meaning ‘southern islanders’, this group of peoples originated on islands and peninsulas in southern Asia, were good at sailing, and used that skill to fan out across the islands of the Pacific.

Some words haven’t changed very much in the course of Austronesian migrations: words like ‘mata’, meaning eye or eyes. The supposed World War I spy Margaretha Zelle’s stage-name Mata Hari meant ‘sun’ or more literally ‘eye of the day’ in the everyday language of the Indonesian islands where she grew up.

Thousands of kilometres from Asia the similar-sounding Māori word Matariki refers to a constellation that rises in the middle of winter and signals the Māori New Year. In Māori, Matariki literally means either ‘small eyes’ (mata-riki) or ‘eyes of a chief’ (mata-ariki). As for Mataruahou, this was originally Mataruahau, a name that meant the reflection of a face in a pool, since mata can also mean face in Māori.

Along with Mataruahou, various other elevated points nearby were also inhabited by Māori, who used the lagoons as mahinga kai, or food resources. The particularly enormous lagoon to the north and west was known as Te Whanganui a Orotū, the great harbour of Orotū, and also as Te Maara a Tawhao or the garden of Tawhao. There are eleven recorded pā or Māori villages on the shores of the great harbour of Orotū alone.

The Hawkes Bay Museum contains two carved wall posts called poupou, one of which is described as the last remaining in the region from a failed 1870s project to build a great, new, Māori meeting-house to be called Heretaunga III, which would have been erected at Pākōwhai, just outside Hastings. It is on the right-hand side of the following photo. The other poupou, also from the same project, is on long-term loan from the National Museum of New Zealand, Te Papa, in Wellington.

The project was initiated by Karaitiana Takamoana, Member of the House of Representatives for Eastern Māori in the 1870s, a man whose biography reads like an adventure novel.

The meeting house, which would have been an astonishing architectural creation and a significant reassertion of Māori cultural identity in the face of colonisation as well, was sadly left unfinished when its political sponsor died in 1879, even though the hard work of carving 61 poupou had been done by then.

The 61 poupou ended up at a government exhibition in Dunedin, and were then dispersed to museums in New Zealand and around the world, with about 30 still remaining in Dunedin’s Otago Museum.

In Hawkes Bay, the local iwi or tribe is Ngāti Kahungunu, whose traditional territory extends from Māhia to Cape Palliser at the southern tip of the North Island.

Ultimately, the Ngāti Kahungunu would lose the best part of their realm, the sites of Napier and Hastings and the surrounding Heretaunga Plains, the only flat land for miles around, for a comparative pittance.

According to an article about the European settlement of Napier, published in 1932,

The purchase of Mataruahou, now Scinde Island, was completed in 1856, cost the Government only £50 and a reserve of two sections for the Chief Tareha and his family “when the land has a town.” The site of Napier and an area up to the ranges inland cost only £1000.

Including the purchase of Napier and the land back to the inland hills from Napier, the total for all Ngāti Kahungunu’s local land sales came to a few thousand pounds.

The chief purchaser of Ngāti Kahungunu lands was Donald McLean, a figure admired by the other colonists for driving hard bargains with the Māori and getting their lands, indeed, as cheaply as possible.

McLean is also buried in the old colonial cemetery on top of Hospital Hill beside the missionaries.

All that, to reiterate, was when Napier was basically an island. For some time, the colonists wrestled with the surrounding waters, which they regarded as a nuisance and in no sense a great resource, in contrast to the Māori.

After a great flood in 1897, some of the land to the south of the island was reclaimed, but the north and west remained an open lagoon.

The lagoon was called Ahuriri in Māori, a name that means the rushing out of water. Apparently, it once overfilled and threatened shellfish beds, so a chief named Tū-āhu-riri had a channel cut to the sea to regulate its level. Ahuriri is also the modern Maori name for Napier, and for a suburb on the site of the former lagoon as well

And then on the third of February 1931 there was the great earthquake, followed by fires. The whole region was affected, though it is called the Napier Earthquake because the damage was worst in Napier.

An organisation called the Art Deco Trust runs tour of the rebuilt art deco city, the subject of last week’s blog. It used to operate out of a building next to the Hawkes Bay Museum and library, though it has now shifted its headquarters. Here is a photo of its bus tours that I took a few years ago.

Modernism and the idea of rebuilding everything from scratch isn’t confined to the central city. There’s a whole suburb of early-modern-architecture houses called Marewa, which is also surrounded by a belt of parkland with walking paths along it.

The grand avenue of Marine Parade, which I also mentioned last week, fronts onto Napier Beach. Which, unfortunately, isn’t very good, nor safe.

However, Ahuriri Beach, adjacent to Spriggs Park on the northern side of Mataruahou, is much better. So is the beach on the former sandspit that used to guard the old lagoon to the west, Westshore Beach, which only has the disadvantage of not being so close to town.

The next photo is of an information panel showing some of the hiking, biking and wine trails of southern Hawkes Bay, which you can access here. These include visits to sites of Māori heritage such as a remarkably preserved old-time hilltop pā at Otatara, accessible via the Otatara Pā Loop Trail. You can download the trail map here, or get the Hawkes Bay Trails App.

A little way south, I came to a place called Waitangi Regional Park where the Tutaekuri River, the Ngaruroro River and the Clive River all come together, and flow out to the sea through a common mouth, with the Tukituki River a little further along down the coast.

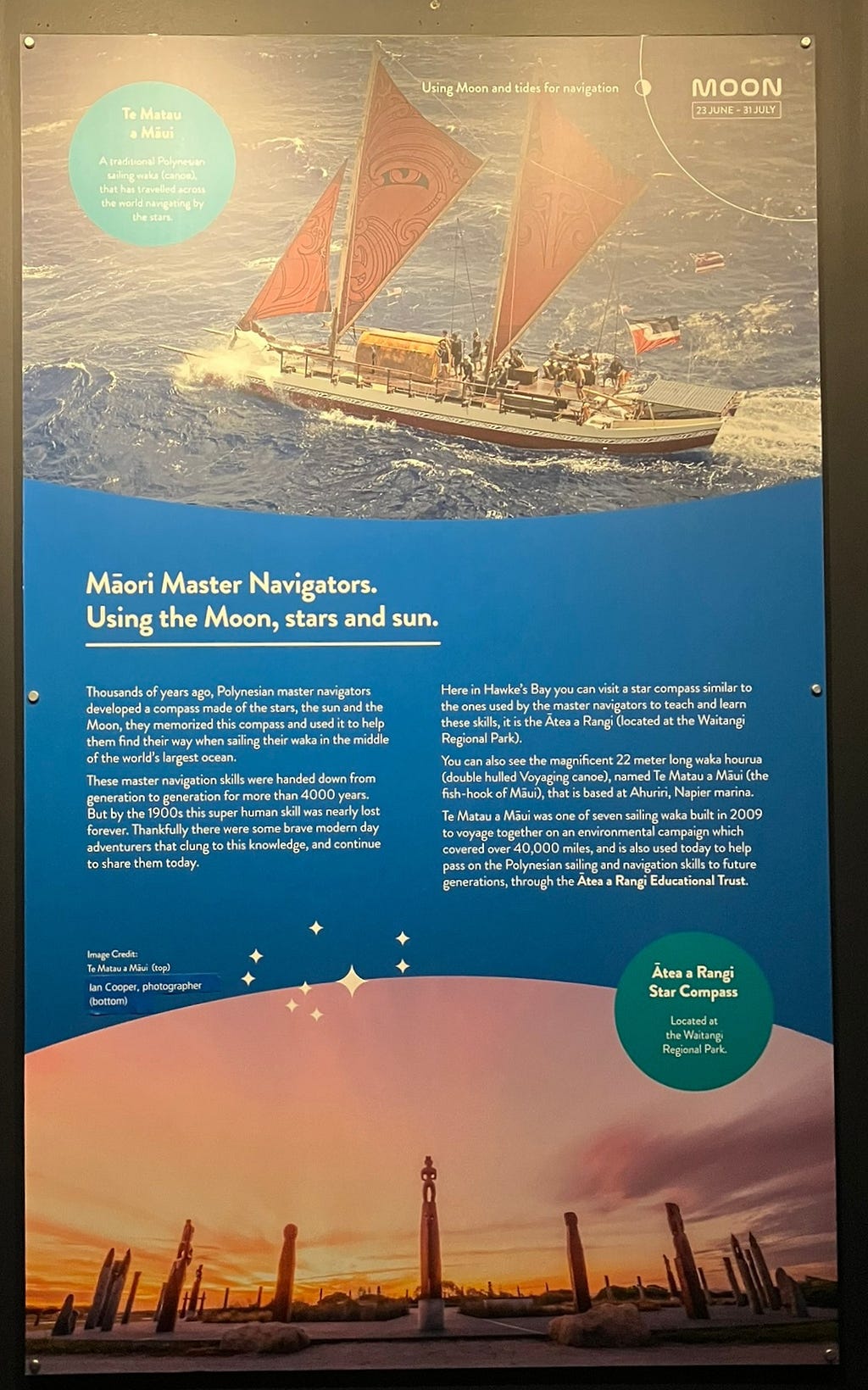

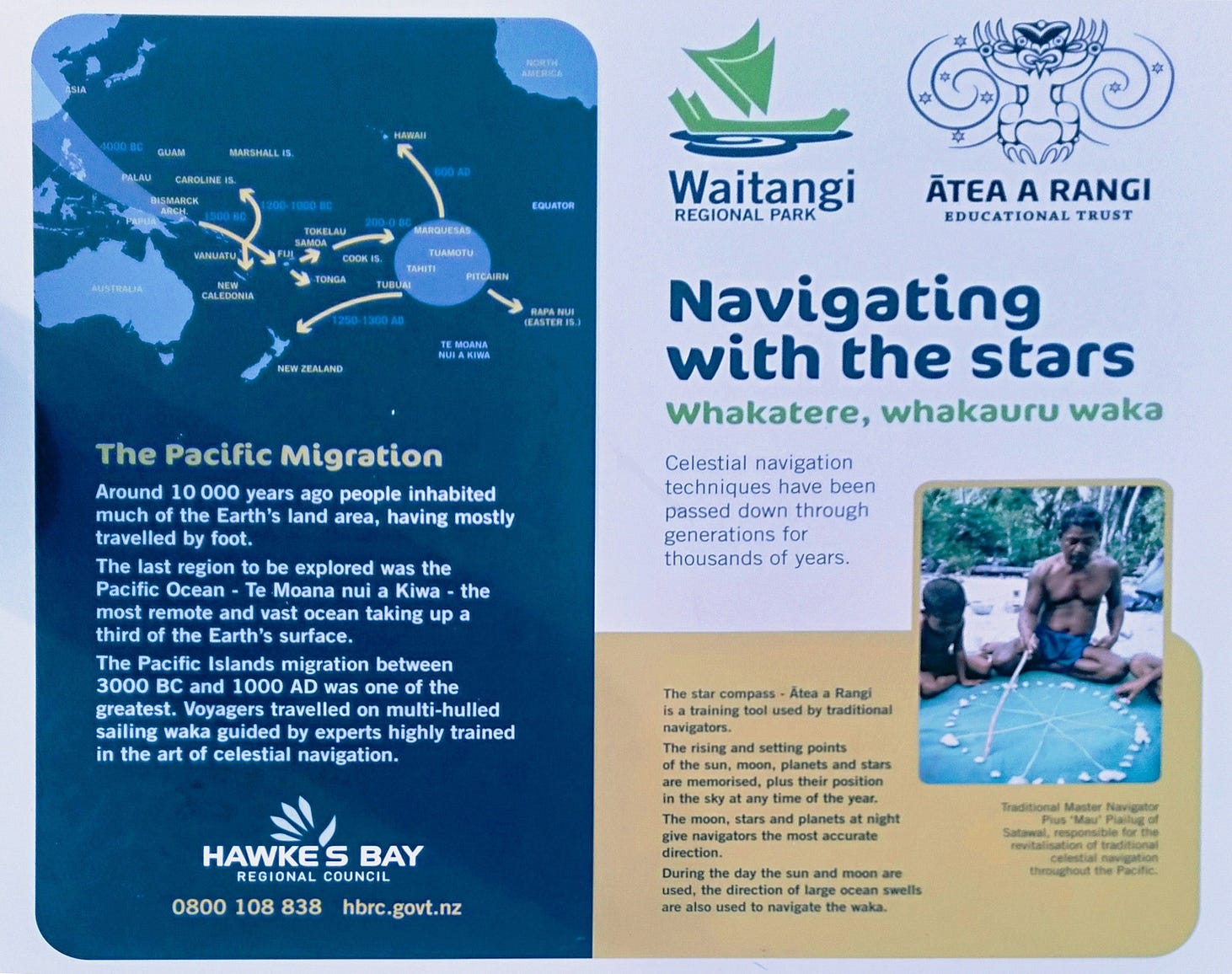

The Waitangi (‘weeping waters’) Regional Park has a circle of carved poles called Ātea a Rangi or heavenly court, which honours the rising of Matariki and also symbolises various aspects of Polynesian navigation, which depended on a careful reading of the stars to determine latitude along with sea-state signs such as the set of the waves and the presence or absence of birds and floating plant debris from some nearby island.

Sea-signs helped with the more difficult task of determining longitude or, in other words, how far east or west the sailors were along a given line of latitude, along which there would be known islands whose proximity could be deduced from the state of the sea.

European navigators like Cook had the advantage of brass instruments, chronometers and sizable ships. The Polynesians must have been all the more enterprising to set out on the biggest ocean in the world in comparatively flimsy craft and to trust navigational methods that depended on such things as whether you‘ve lately seen a floating coconut, or not.

The Waitangi Regional Park has many historical information panels, including the ones I’ve shown above about William Colenso and Polynesian migration and navigation. Here’s a video I filmed there:

There’s also the very latest thing: here are some posters for bands performing at the local Paisley Stage Live Lounge (which has a Facebook page as well).

I think the next one, a rather gothic outfit called High Altar, advertising its Adoration of St Denis tour, believes in keeping Catholicism weird.

Finally, last but not least, there’s an unusually excellent fish and chip shop just off Marine Parade, Continental Fish Supply, on the corner of Hastings Street and Sale Street. Its chips are crunchy!

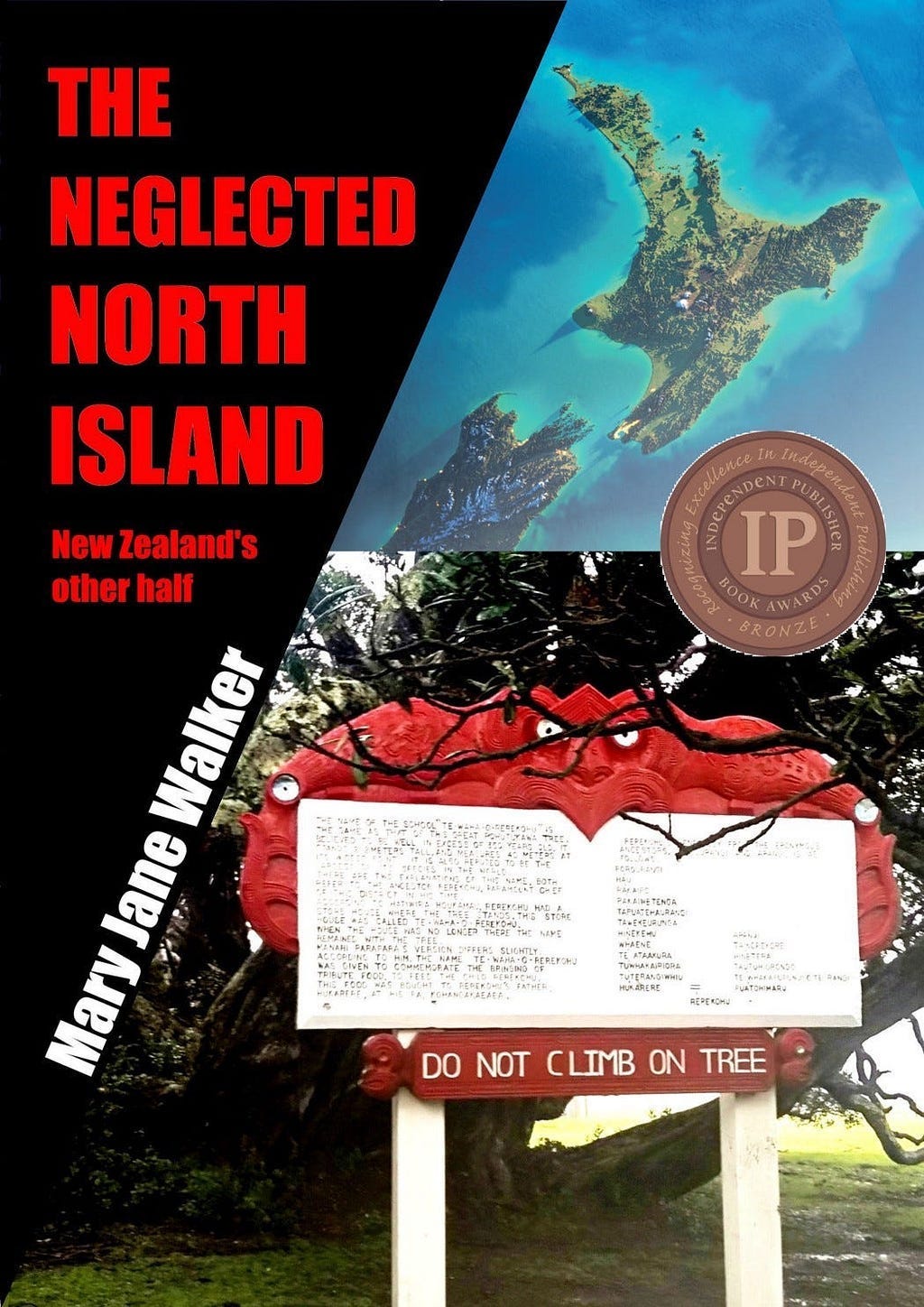

If you liked this post, check out my book about New Zealand’s North Island! It is available for purchase from my website, a-maverick.com.

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive free giveaways!