This post has been superseded by 'From Whitestone to Bluestone,' published on 27 February 2026.

FROM Oamaru, I drove north to the similarly-named town of Timaru.

The towns are twins in some ways. They’re both local ports founded in colonialtimes, with plenty of colonial architecture. And both seem to take their names from the same source, the Māori word maru.

By one account the source is Maru with a capital M, an ancestral hero of the local Māori iwi (tribes) and hapu (bands). In this version, Timaru is short for te Tihi-o-Maru, the topknot of Maru. Oamaru is short for te Oha-a-Maru, the gift of Maru.

Others say that the source is maru with a little m, in the sense of a good spot to camp or haul boats ashore.

And there are other explanations, of possibly dwindling credibility compared to the two main theories.

Whatever the precise origin of its name, Timaru sits toward the southern end of the great sweep of the Canterbury Bight, which starts just south of Christchurch. The harbour of the town itself has the lovely name of Caroline Bay.

The town lies on undulating terrain, made from lava flows that once cascaded from a nearby extinct volcano called Mount Horrible. The basalt lava of Mount Horrible is called ‘bluestone’. Along with smaller quantities of granite from the same volcano, it was used to build the colonial town in just the same way that Oamaru was built out of local ‘whitestone’.

Halfway between the two ‘maru’ towns, I took a short detour into Waimate. Waimate is a Māori name which literally means ‘Deadwater’, like somewhere in the Wild West. The town is the birthplace of the fondly-remembered Prime Minister Norman Kirk, who came to power in 1972, at about the same time as Gough Whitlam in Australia.

Kirk was always quite reasonable and intelligent, in a way that is completely different to many of the politicians of today. He’s interviewed in the first part of this clip.

Unlike Whitlam, who lingered on in bitterness for nearly four decades after being deposed in 1975, Kirk tragically died in his first term of office. And so he stares at us Kiwis through the years with an expression rather like that of John F. Kennedy, provoking a similar sense of what might have been.

Waimate was a nice town, unassuming but with a ton of history behind it.

A hundred years ago, there weren’t as yet very many female medical graduates in New Zealand. Their ranks were diminished further when local GP Dr Margaret Cruikshank was fatally infected while caring for patients during the 1918 influenza pandemic, to which the present coronavirus outbreak is being compared. Hopefully we won’t be erecting any more like this.

I wonder whether this statue inspired Kirk to his life of public service? He’d have gone past it every day as a boy.

It was December of 2019 when I was there, and so I was more interested in the fact that Dr Cruikshank was the first female doctor to qualify in New Zealand. If I gave any thought to manner of her demise, I’d have supposed that all that was safely consigned to what the rapper Gil Scott-Heron once called “a black-and-white movie from ages ago.”

I struck up a conversation with a French traveller in a modern-looking cafe, and noticed that the town had more than one wildlife park featuring a collection of wallabies, which are like small kangaroos.

I was surprised: I thought wallabies were a considered a pest in this part of New Zealand. They were brought over from Australia for the fur trade in colonial times, but soon hopped away and started eating the farmers’ crops.

In fact, they seemed to be quite proud of being over-run by wallabies in Waimate.

All sorts of plants and animals introduced to New Zealand by its settlers, both the Māori who introduced Polynesian crops, small dogs and a species of rat, and still more so the Europeans who came later, have turned into pests.

As in Australia, perhaps one of the worst mistakes was the introduction of the rabbit. Lacking natural predators, it exploded in numbers and started eating the farmers’ crops down to the ground. So, other people introduced stoats, weasels and ferrets to eat the rabbits. But those creatures found New Zealand’s native birds to be much easier prey. And so on, and so forth.

I guess it’s fair to say that wallabies probably aren’t as bad as stoats as introduced pests go. And probably cuter as well.

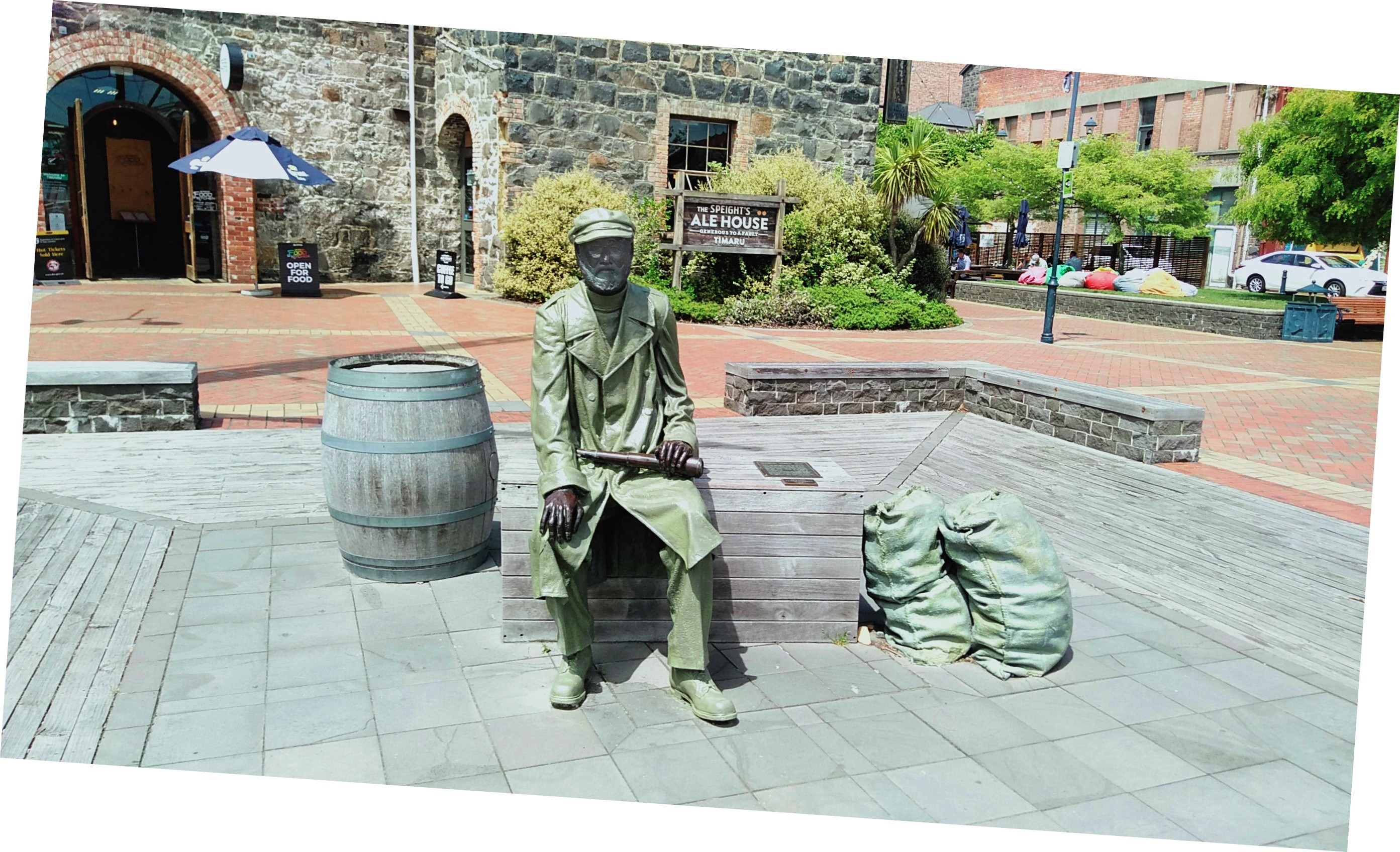

As Oamaru is whitestone, so Timaru is bluestone.

The building in the last photo, now a backpacker hostel, is called the Dominion Hotel according to the old lettering at the top. But in its day it would probably have been known to the townsfolk primarily as a pub or bar. For ‘hotel’ is a New Zealand euphemism for a liquor establishment dating back to the days when the clamour for Prohibition was strong, along with the odd counter-demonstration.

Straight-out pubs and bars actually did end up being prohibited, or at least fairly severely restricted. But you were still allowed to drink freely on the premises of a hotel. So, the owner of every boozeroo made sure to put in a few rooms upstairs. Sometimes the hotel side of the business was serious and reflected in serious architecture, as with the Dominion Hotel. Other times it was more token in nature, another level on a flimsy structure with floors that did little to block the transmission of noise from the bar below.

One of the other hotels in Timaru is called the Hydro Grand, a reflection of the days when Timaru pubs — sorry, hotels — would be patronised by workers from South Island hydrolectric schemes on their days off.

New Zealand ‘hotels’ tended to have almost absurdly respectable-sounding names. The Dominion, as we’ve seen. The Grand. The Royal George. The Royal Oak. The Naval and Family. The Gladstone, named after a famous British Prime Minister. Or a little more obscurely perhaps, the Star and Garter, named after noble orders of chivalry. Establishments that served beer thus fended off further attempts at closure by becoming pillars of the Establishment themselves.

Grand premises aren’t confined to town. Part of the way up Mount Horrible, there’s a stately home and function venue called Castle Claremont. Built of local granite with whitestone details, Castle Claremont is perhaps in some ways even more grand than Larnach’s Castle near Dunedin.

But Castle Claremont is less well-known since it’s in a more remote spot. It was built in 1884 by the Rhodes family, originally from Yorkshire. The Rhodes family were big names in colonial New Zealand. I imagine that they were probably distant relatives of Cecil Rhodes, though he was born at a time when the New Zealand branch of the clan was already well-established.

I loved the way that Timaru’s old buildings clustered around the waterfront and beaches of Caroline Bay. Back in the day, Timaru had a reputation as a sort of Riviera by the sea — like much of New Zealand, in actual fact.

Indeed, it pretty much still is like that.

Here’s something unusual, a sign honouring local worthies in order to inspire the young people of the town.

South of the town, on Saltwater Creek, there is the Otipua Wetland, sixty to seventy hectares or a bit less than two hundred acres of marshy habitat that has been under restoration, by an army of volunteers, for more than twenty years. I got some good photos there too.

The wetland joins up to a coastal track that leads both northward back to the town via Patititi Point, and southward to another prominent coastal point.

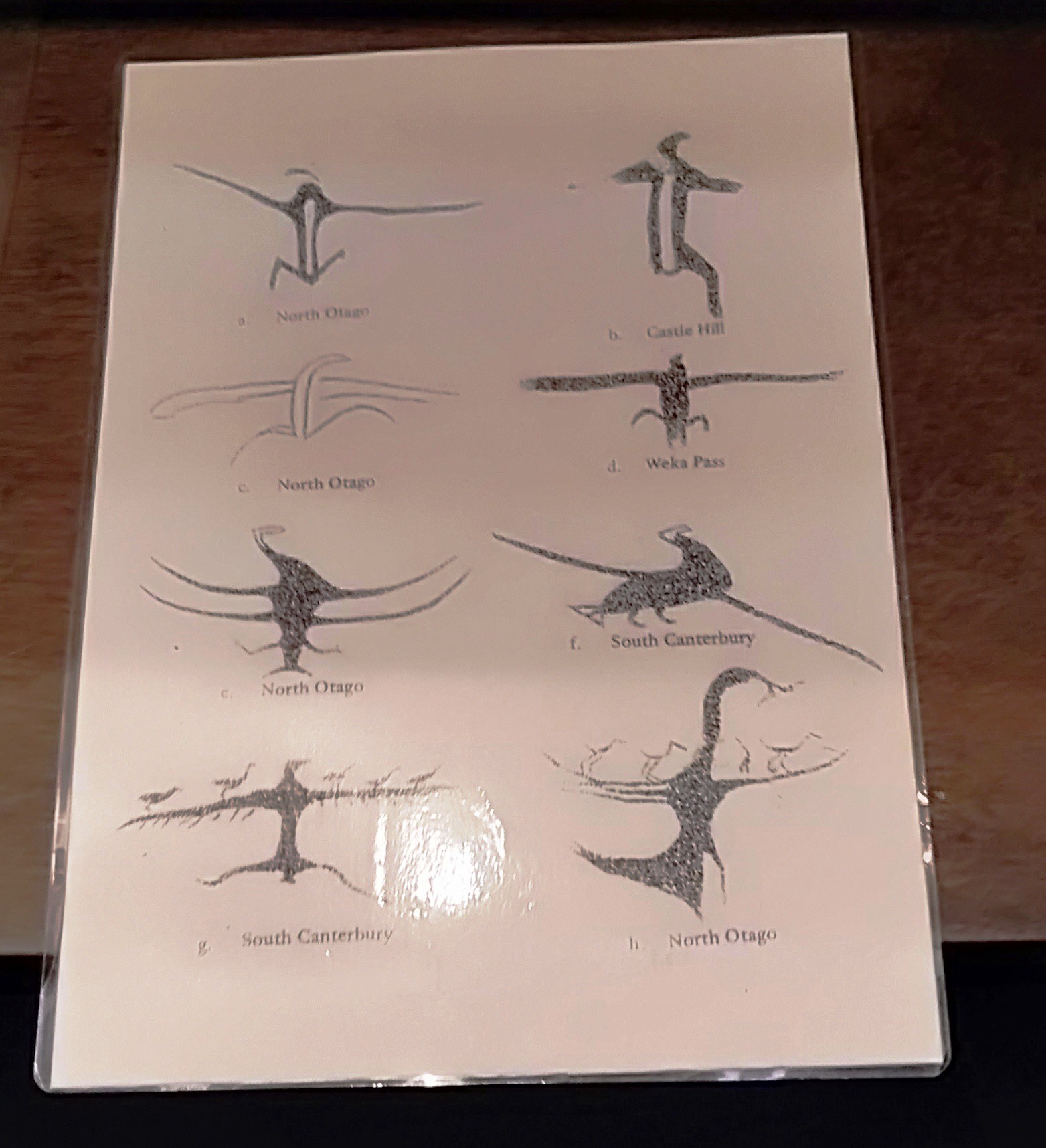

To round off, I also went to the amazing Te Ana Rock Art Centre, run by the biggest South Island iwi, Ngāi Tahu. Te Ana means ‘The Cave’. It displays rock art done by some of the earliest Māori to settle in the region, basically the local equivalent of European ice-age cave-paintings or Aboriginal rock art in Australia. Such ‘primitive’ art is often amazingly polished and dynamic, as in this museum replica of French cave-paintings of lions . . .

. . . and the New Zealand version is no exception. At Te Ana, the local Māori seem to have anticipated Pablo Picasso. As do the Chauvet Cave paintings, come to think of it.

Te Ana is conveniently located in downtown Timaru, in George Street. The museum also runs guided tours into the countryside, to investigate the actual honest-to-goodness caves.

This is what I mean about Picasso:

Unfortunately I wasn’t able to get a sharper photo! To make up for it, here’s a video of a projected display showing many of the same designs.

Māori rock art has sometimes appeared on New Zealand postage stamps. There are some images of a 2012 series, here.

Many of the rock drawings at Te Ana are a bit different in appearance to what most people would think of as traditional Māori art, works such as this, which scholars describe as being in ‘classic’ style:

The differences arise partly because the rock art at Te Ana is a few hundred years older than the ‘classic’ style. Its origins and significance are also much more obscure. A lot of classic Māori art, like the carving described just above, has a detailed provenance. On other hand, as the first of the following Te Ana displays says, “We don’t know exactly who made the rock art.”

But South Island Māori are also somewhat distinct from the the more numerous North Island Māori, the main originators of the classic style, in any case. The person in charge that day, named Wes, filled me in on the local indigenous history as well as some of the differences between the Māori of the South Island and their North Island cousins.

For instance, in the dialects of North Island Māori, on which the official form of the language is based, many words have an ‘ng’ sound like the ng in ‘singing’, written the same way. Ng often appears at the start of words as well as in the middle or at the end: in words like ngarara (‘lizard’) or Ngauruhoe, a volcano in the central North Island.

In the South Island, the ng changes into a ‘k’. And so the other name for Mount Cook is Aoraki, a poetical term meaning something like ‘cloud in the sky’ since the mountain is so tall and snowy, even in summer. In North Island Māori, this would be Aorangi. And the Waitaki River which divides the historic provinces of Otago and Canterbury, its name meaning ‘water of tears’, is the equivalent of Waitangi in the North Island.

Ngāi Tahu records its name with an ‘Ng’ for official purposes and on the Te Ana website too, but it’s Kāi Tahu when it’s at home.

There are other differences that are perhaps not so well-recorded, some minor iwi or hapu having been absorbed into others and their local dialects extinguished in the general upheaval of colonial times.

The names Otago and matagouri (a thorny shrub) come down to us from the early settlers but they are of Māori origin. Both have a ‘g’ in them that isn’t supposed to be there in any form of Māori, North or South. Did some now-vanished tribe actually speak that way?

In the next post I’ll be talking about Timaru’s railway history, and whether passenger trains might ever ride the rails once again in these parts.

The Te Ana website is linked in the text, but here it is again: teana.co.nz

For more on Timaru attractions in general, with an emphasis on things you can do for free, see wuhootimaru.co.nz

If you liked the post above, check out my new book about the South Island! It's available for purchase from this website.

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive free giveaways!