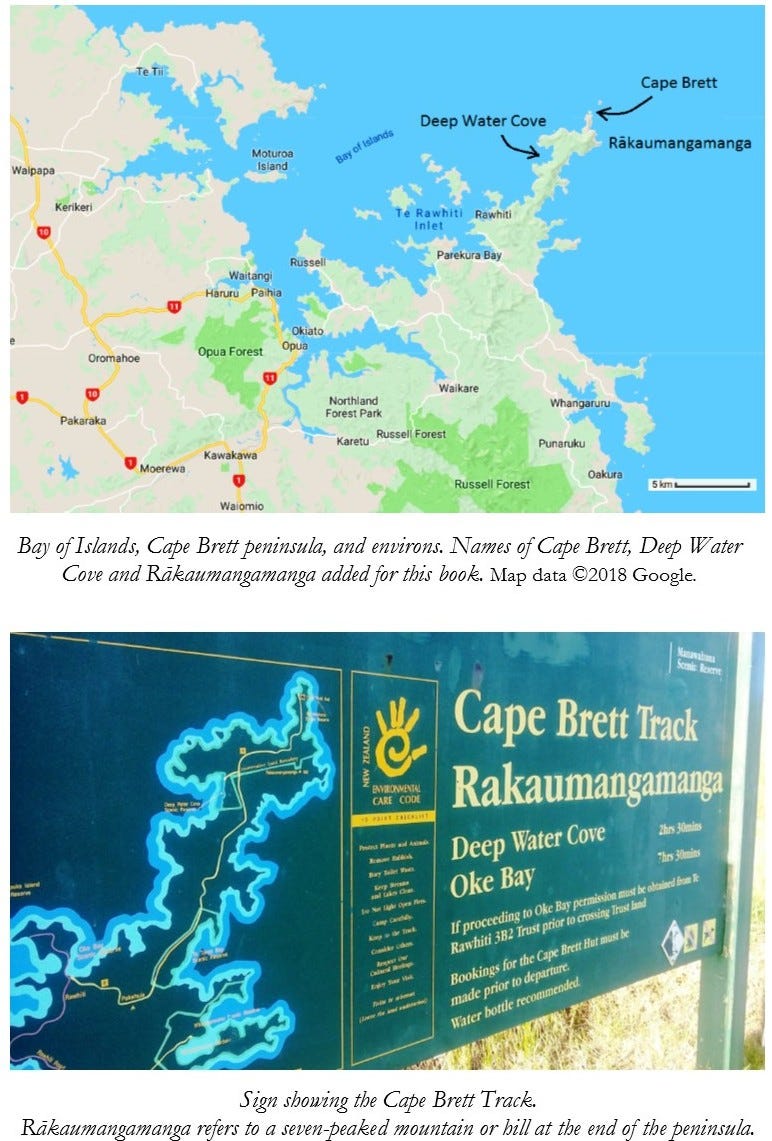

ONE of the most famous places in New Zealand is the Bay of Islands. As its name suggests, this gorgeous bay on the east coast of Northland, due north-east of Waipoua Forest, is full of islands. The Bay of Islands is protected from south-easterly ocean swells, and from any cold southern winds that make it this far north, by a hilly peninsula leading to Cape Brett. A track leading along the peninsula to the cape is the subject of this blog.

I’ve included maps and some photos from my book A Maverick New Zealand Way, so that’s why the next caption refers to a book!

But first, some background on the Bay of Islands. The Bay is fairly touristy these days, though not as touristy as some other places in New Zealand. For a long time, the Bay of Islands attracted domestic holidaymakers, plus wealthy visitors intent on catching big fighting fish such as Marlin.

The American author Zane Grey wrote about the place in the 1920s, popularising it in a book called Tales of the Angler’s El Dorado.

Before that, the Bay of Islands was the seat of New Zealand’s very first capital at Russell; and is the site of the Treaty House, where the founding Treaty of Waitangi was signed on the 6th of February, 1840, between Queen Victoria’s representatives and a number of Māori rangatira, or chieftains.

With global warming, the area north of Auckland is slated to become more tropical. It is lashed from time to time by cyclones, and this is likely to get worse. However, between storms, it’s a lovely part of Polynesia. That’s particularly true of sheltered east coast areas like the Bay of Islands. A bay which we must now depart for the Cape Brett peninsula which shelters it, and the campsites near the peninsula.

I stopped in first of all at the Bland Bay Motor Camp near Whangaruru, which Is toward the bottom right of the map just above. This area, south of the Cape Brett peninsula, is a refuge from the busier and more commercialised Bay of Islands proper. The Bland Bay Motor Camp is run by the Ngāti Wai iwi.

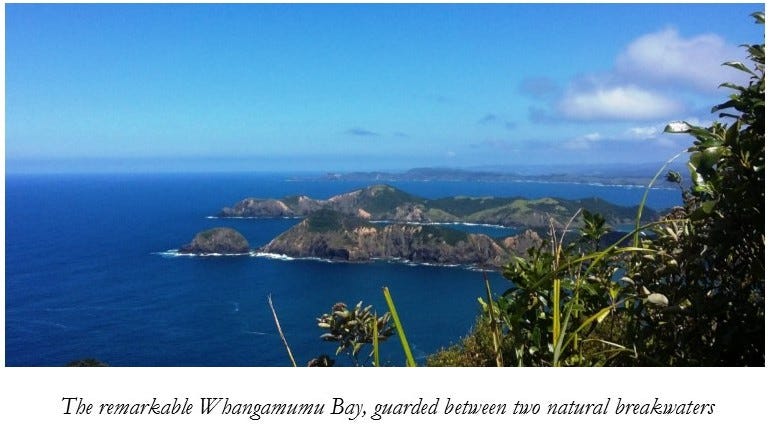

I went for beautiful walks around Bland Bay and nearby Puriri Bay. I stayed there for three days just relaxing, but then I thought that I had to take up the challenge of hiking the length of the Cape Brett peninsula toward a jagged, seven-peaked massif known as Rākaumangamanga — which forms the most seaward part of the peninsula — and ultimately to Cape Brett itself.

The Rākaumangamanga massif is of great significance to Māori as the arrival-place, and subsequent branching-out place, of seven ancestral ocean-going canoes — double-hulled and more like catamaran yachts — on which the ancestors of the Māori were said to have arrived from a homeland called Hawaiki roughly one thousand years ago.

Hawaiki looks like Hawaiʻi and is really the same word. However the ancestral Hawaiki is not in the same place as modern Hawaiʻi. It is thought to lie in today’s French Polynesia.

A Tahitian named Tupaia, who sailed for a time with Captain Cook, was able to interpret between the British and the New Zealand Māori. Cook was amazed at this, for Tahiti is a very long way from New Zealand. Clearly, the coming of the Māori had been no mean feat of navigation.

In the traditional account, the canoes made for Rākaumangamanga and then went their separate ways to settle different parts of New Zealand.

In New Zealand Māori there are two words that are translated as tribe and sub-tribe respectively: iwi and hapū. An iwi is made up of several hapū, or clusters of close relatives. Iwi lineages date back to founding canoes. The iwi was the largest unit of government to exist in New Zealand before the coming of European colonisation.

Aotearoa is the Māori word for New Zealand, or for Māori New Zealand. It was coined in the nineteenth century as British colonisation forged a greater sense of common identity among separate tribal groups.

Thus, the stories about Rākaumangamanga paint it as the place where Aotearoa was born; albeit ironically in the form of the parting of the canoes and the establishment of the iwi system.

Whence, also, the name Rākaumangamanga. The Māori word rākau means tree or stick, while manga means branch. Doubling up the word manga adds emphasis. The name is associated with the the branching-off of the canoes, and maybe the the branch-like shape of the peninsula as well.

The seven peaks of Rākaumangamanga represent the original colonising fleet.

However many vessels there really were, and whether they all came at once or not, the legend’s theme of a deliberate and organised process of colonisation is backed up by modern research.

The ancestors of the Polynesians lived on islands off the Asian coast, where they were related to other island peoples such as the majority of the inhabitants of Java, and the indigenous people of Taiwan.

The Polynesians gradually spread eastward into the Pacific Ocean, often known in New Zealand Māori as Te-Moana-nui-a-Kiwa, the Great Ocean of Kiwa (a legendary guardian of the waters). The word moana, as in the film of that title, means ocean or sea in most of the languages and dialects of Polynesia.

The islands of New Zealand were the last and largest islands to be colonised by Polynesian people; who also frequently called themselves Māori or a similar word wherever they lived. This meant ordinary or common, as opposed to other peoples that the Polynesians sometimes met such as the Europeans who began arriving, in earnest, in the eighteenth century.

The islands of New Zealand would have been the most challenging to colonise, since they were well south of the main latitudes of Polynesia, with different wind patterns and colder seas. So, the Māori colonisation of New Zealand could have required a particularly organised expedition, or series of expeditions.

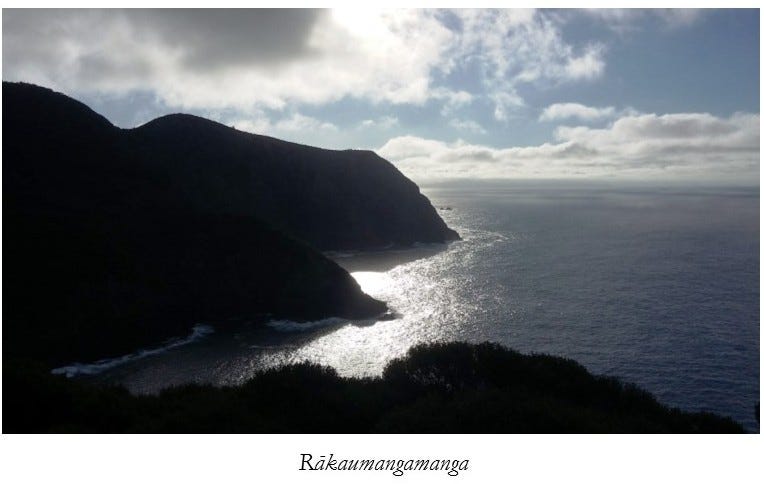

For anyone intent on hiking Cape Brett peninsula to its tip — where the whole human history of New Zealand is said to have begun — the first thing to mention is that the track takes about eight hours from start to finish.

There is an excellent Youtube video called ‘Cape Brett Track — Living a Kiwi Life — Ep. 45’, which has been recommended by New Zealand’s Department of Conservation (DOC), and which gives a very good idea of what the track is like, including the exposed bits which may not be for everyone.

‘Cape Brett Track — Living a Kiwi Life’, Ep. 45, by Stoked for Saturday

In several places it gets gnarly and exposed, with big drop-offs to either side, though the views are terrific.

The track is administered by DOC, with a seaward part on DOC estate and a part which is closer to the mainland crossing the estate of traditional Māori owners. The track is graded as ‘advanced’ in its DOC brochure, a grade which falls short of mountaineering but does mean that it is a good idea to be kitted out with boots and hiking poles and proper tramping gear all round, along with having a reasonable level of fitness and a head for heights. The track is not open to mountain bikers, because it is actually too steep and (potentially) dangerous for that.

There are several carparks at the beginning. A lot of cars get robbed, though you can pay $8, currently, for more secure parking. There is a stream and a water tank halfway along the track, but carrying water is recommended. I would recommend carrying water purification pills as well.

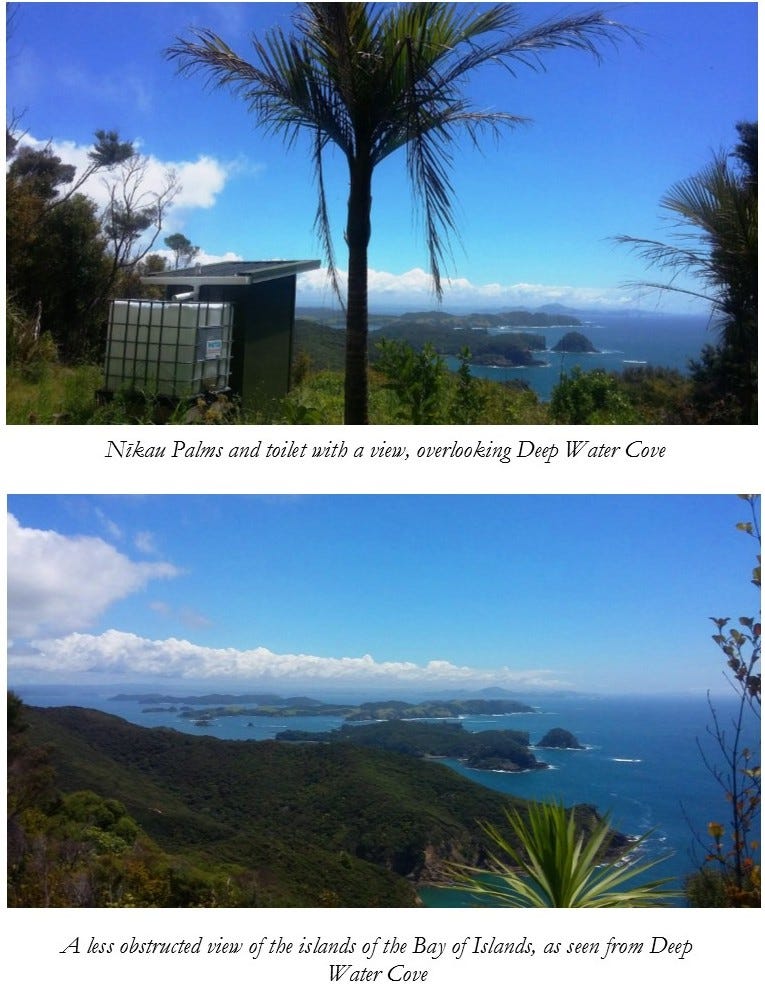

You can make side-trips from the main track to the old Whangamumu Bay whaling station and other areas of interest. Whangamumu Bay is well worth it, a white sand beach sheltered by two peninsulas that act as natural breakwaters.

Further along, you get to Deep Water Cove on the western side, which has terrific views of the Bay of Islands. This also be enjoyed from a strategically-located toilet, though only with the door open of course.

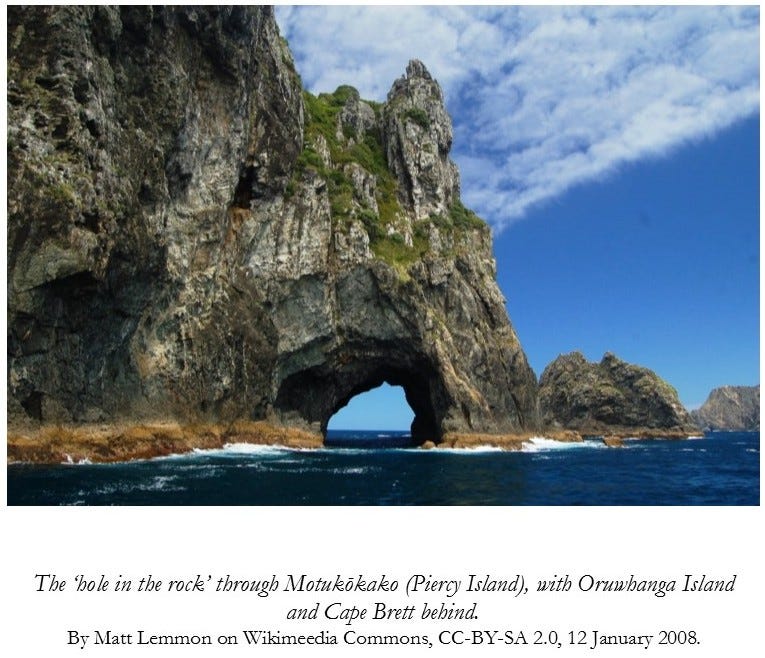

For those who don’t want parking hassles or too long a walk, it’s possible to take a water taxi from various Bay of Islands localities such as Russell, Paihia and Oke Bay to Deep Water Cove or Cape Brett. One advantage of taking the water taxi all the way to or from Cape Brett is that if sea conditions allow, the taxi may go through the famous ‘Hole in the Rock’ at Motukōkako (Piercy Island) just off Cape Brett.

The water taxi costs $50 per person to or from Cape Brett at the time of publication, or $40 to or from Deep Water Cove, but minimum per-boat charges apply, i.e. it must have a quorum of passengers (about five), or else the rate per person goes up. Details are on the web here.

The main reason that Rākaumangamanga features so prominently in tales of Polynesian colonisation of New Zealand, is because it was a natural beacon. The Cape Brett peninsula terminates not only in seven hills but also in a long line of eastward-facing cliffs, well out to sea in the direction from which the first Polynesian colonisers would come. The cliffs would be lit up by the first rays of the morning sun, making them visible from a great distance.

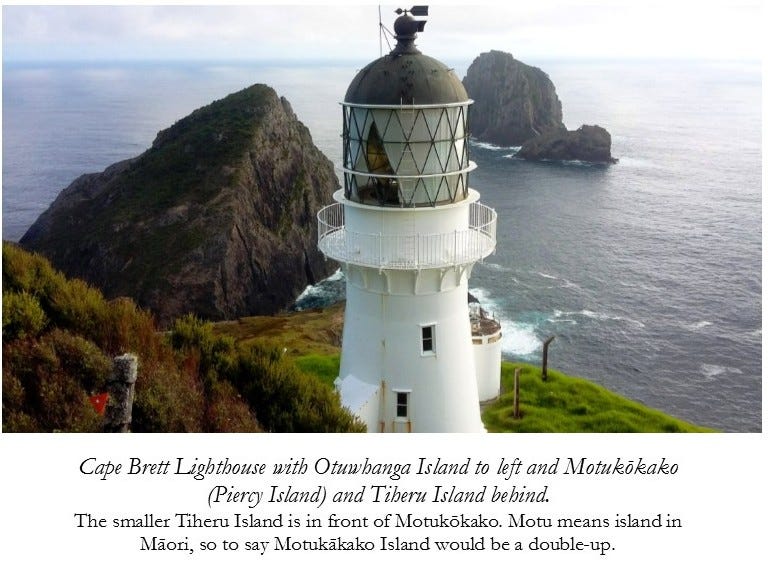

Much later, the Cape Brett Lighthouse would be placed in the same location, providing illumination through the night.

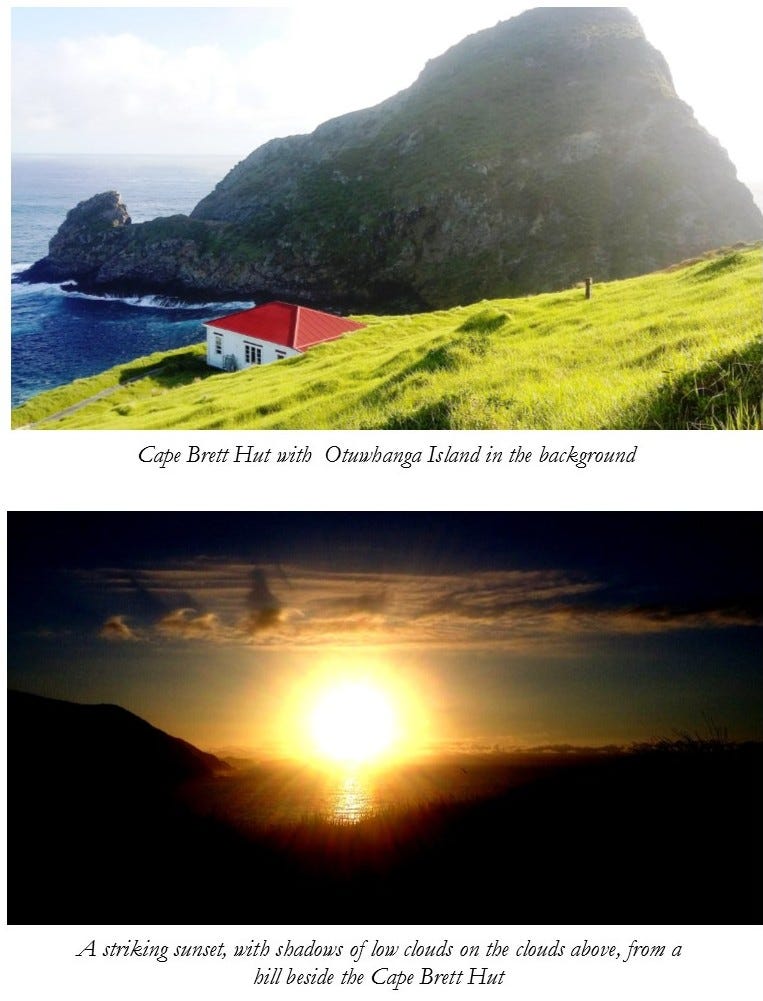

Near the Cape Brett Lighthouse is the so-called Cape Brett Hut, overlooked by the massive looming presence of Otuwhanga Island. Rather flash as huts go, it used to be the lighthouse keeper’s house before the lighthouse was automated.

It’s necessary to book the hut in advance if you want to stay there. It has a combination lock, and you get the combination on booking. Currently, the fee is $15 a night for an adult (18+), half-price for those 11–17. Younger children are free.

I saw a stoat running along the track. Fingers of land like the Cape Brett peninsula are obvious candidates for being fenced off and made predator-free. It’s a sign of DOC funding stress that they aren’t.

There is also a fee for walking along the part of the track that crosses Māori land, which goes toward the maintenance of the track on that section. The fee is currently $40 per adult or $20 per child. The fee is paid on the DOC website. The website capebrett.co.nz, which also provides the details on the water taxi, notes that the arrangements for paying the fee on the DOC website are rather confusing and provides helpful tips on how to get it right.

The fee can be avoided by taking the water taxi both ways, though this means missing out on a portion of the track. In an ideal world the Māori landowners would be fully compensated by DOC, but I suspect that neither the department’s budget nor, perhaps, its present organisational capabilities run to that.

So, all in all, I would really recommend the Cape Brett Track. But there are a few things that could be improved upon if DOC had more resources, as is the case almost everywhere in outdoor New Zealand.

Here is my Amazon author page. I’m also publishing my books, progressively, on other platforms.

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive free giveaways!