BACK in 2019, I published a blog post about how I was trying to build a small but affordable house of 70 square metres (753 square feet) on my site in Queenstown, New Zealand.

At that stage, I had just had a retaining wall built, with a carpark below, with the intention that the small house would be perched on top.

Among other things, I thought that — once built — the small house would command quite good views of Lake Wakatipu and the Eyre Mountains on the other, less populated side of the lake (about which I am shortly going to publish another blog post, having driven through the Eyre Mountains in my camper van just last weekend.)

For the next few years, as you can tell from the growth of weeds, nothing happened.

Nothing happened, as I investigated the various possibilities, none of which seemed very attractive. One came in at NZ $900,000, mainly because of the cost of building additional retaining walls to accommodate a house that was to bite into the slope by another six metres behind the existing retaining wall.

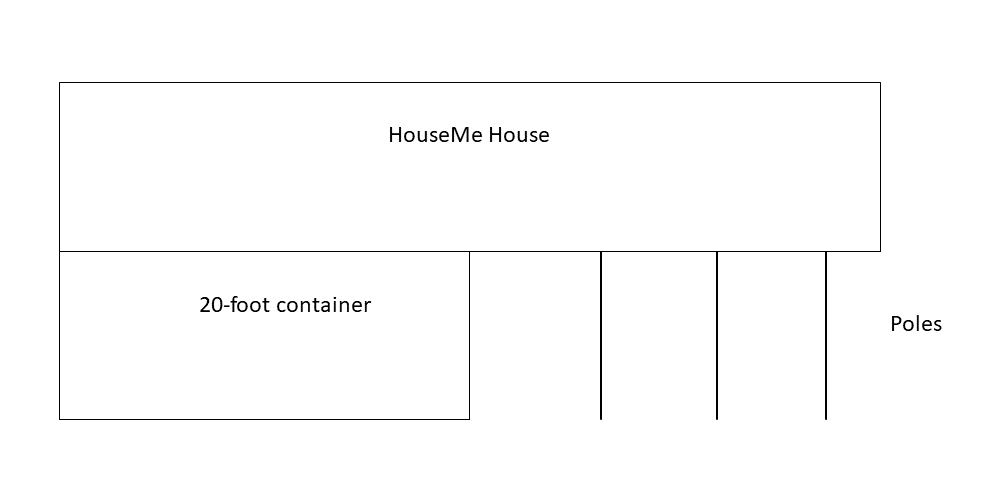

Well, just lately, I have put a deposit on a 12.5 metre by 3.4 metre tiny house, from HouseMe, for NZ $ 138,000 plus delivery. The tiny house is built from scratch, to the same length as a forty-foot shipping container so that it can be easily delivered by truck. The long thin shape suits my steep section much better than a house that is six metres wide.

What finally clinched the deal is that the HouseMe tiny house comes with a Code Compliance Certificate (CCC), which means it is up to New Zealand’s building codes for fixed dwellings.

Many transportable tiny homes on offer in New Zealand don’t have a CCC, and it is up to the buyer to get one. For instance, sometime after rejecting the $900,000 option, I planned to install a very attractive and cheap expandable house from Expanders, 5.8 metre by 6.3 metre once expanded, with a base price of only NZ $36,500 at the factory gate.

I was going to mount the Expanders house on top of a 40-foot (12.5 metre) container, partly overhanging the carpark, to create a total floor area close to 70 square metres but without having to dig into the slope too much.

Unfortunately, the Expanders house did not come with a CCC, mainly because of inadequate insulation (about which the NZ Govt is very strict these days), and so I could not permanently install it on my property. However, if I mounted it on wheels, I could have got away with parking it on my property because it would then have been classed as a caravan, for which the rules concerning insulation are not yet so strict.

This shambolic situation, by which many tiny homes on sale are technically caravans, with no hope of being approved as permanent residences in many council areas — meaning that permanent connection to services is also out of the question — is a real disappointment after six years of a Labour-dominated government, elected in 2017 with a mandate to solve the housing crisis.

You would think the previous government could have at least sorted out some universal system of CCC compliance for tiny homes after six years. After all, they did see fit to make the rules concerning insulation stricter. Why did they not sort out this issue as well?

After all this, what I am now settling for is only a tiny house, about 42.5 square metres: not the 70 square metres I had originally planned for.

As things stand, a 70-square-metre house costs at least $200,000 at the factory gate, as with Sunshine Homes, and potentially $300,000 as with Lockwood.

And it costs a lot more to get transported to site, foundations built, and hooked up to services, even without retaining wall hassles.

As with the Expanders house, which turned out to be a non-starter over CCC issues, I had thought of erecting my HouseMe tiny house on top of a shipping container for extra space. Something like this, perhaps:

But it seems that anything to do with a shipping container is very hard to get permitted in Queenstown as well. So, I am just putting the HouseMe house on ground level and settling for 42.5 square metres.

Thinking some more about all of this, what if a mass-produced small house in the 60 to 70 square metre class could be made narrower, say with a lower part of the same dimensions as the HouseMe tiny home I ordered?

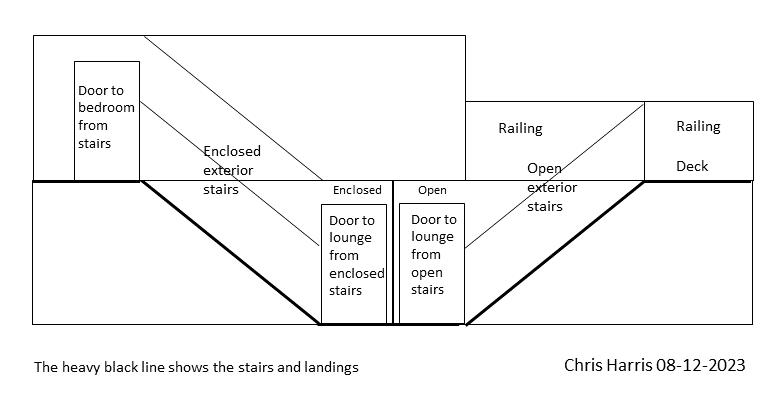

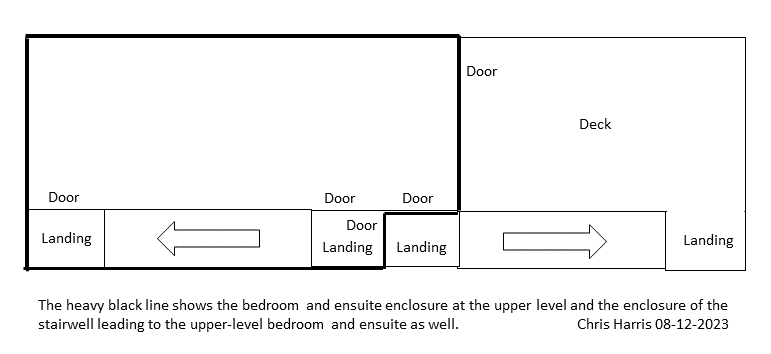

And with an upper-level bedroom and ensuite of half the length (6.25 metres), and an upper-level deck, both accessible by way of stairways attached to the rear, or up-slope, side of the building?

The elevation (side view) and plan (top view) of such a house follow, along with some ideas of how they could be made cheaply. This information is supplied by my colleague Chris Harris, who has an engineering background.

Such a design would allow the optimum use of a sloping section like mine, and, in fact, a whole host of sloping sections in New Zealand that are otherwise too steep to build on in any economical way, without forcing people to settle for tiny homes.

(A tiny home is, technically, anything under 50 square metres. In the 60 to 70 square metre range the house is usually called small, not tiny).

Suppose we were going to make a lot of these two-storey units, of 65 square metres each, as a standardised design suitable both for sloping sections and, of course, flatter sites as well. And for that matter, for putting together to form larger units of 130 or 195 square metres as families grew.

The most straightforward way to build such a house would be with a light steel frame for the lower part and another light steel frame for the upper part, manufactured in a factory in that form. The frames would be bolted together on site.

The frames would then be clad and roofed with exterior-grade structural insulated panels or ‘sandwich panels’ of the steel-insulation-steel type (also known as metal insulated panels or MIPs, in steel), of equal length to each surface that is to be clad or roofed (‘longrun’ steel MIPs, analogous to longrun steel roofing sheets).

Longrun steel MIPs are by no means an experimental or hard-to-source technology. New Zealand suppliers include Bondor, Kingspan, and Metalcraft, to name just three. Indeed, they are increasingly used for longrun roofing, in preference to the older un-insulated steel sheets, as well as for wall cladding.

The longrun steel MIP cladding and roofing panels would be attached in such a way that they bear part of the load along with the steel frame: an approach known as stressed-skin or monocoque construction.

Mechanically speaking, a metal skin that takes part of the load has the advantage of allowing a lighter and cheaper frame behind. This is precisely why aircraft and automobiles came to be built that way some eighty or so years ago. Added strength is also a well-known advantage of steel roofs, as compared to those that are made from brittle materials.

Although steel and other metals are normally thought of as energy-intensive, in reality, they are capable of almost indefinite recycling from scrap metal. This requires some energy to melt the scrap, but this energy is only a fraction of what is needed to make metals from ore, and can be supplied in the form of renewably generated electricity. An abundant source of recyclable steel also exists in the form of old car bodies. As such, the use of steel is a ‘green’ approach to construction.

Pre-shaped insulating foam blocks similar to the ones in which new appliances are packaged would then be fitted inside the steel frames, covering their ribs and supplying further insulation to meet the most exacting codes.

The foam blocks would have flat faces facing the interior and cutouts for the services. Flooring and plasterboard would then be attached to the flat faces of the foam blocks — and that would be it.

The house would be structurally complete at this stage apart from the stairs and landings. These could be made from one long sheet of metal, suitably folded on a machine called a press brake.

Such an approach to the construction of small houses would require a commitment to a high degree of standardisation and large volumes of sales, which in practice would have to be guaranteed by the government, just like the production of aircraft in World War II.

Or the state houses of the same era, which were also government-guaranteed but built by more traditional methods, in part because of a shortage of metals by the standards of today.

This shortage was imposed both by the wartime constraints mentioned in the black and white documentary just above, and by the fact that New Zealand did not make any steel products domestically until the 1960s. Every sheet of corrugated iron that we used before the 1960s was imported. Even the ability to melt down car bodies and re-use the valuable steel from which they were made was only developed, in this country, as recently as the 1980s. Before that, the bodies of cars that died in New Zealand were unceremoniously interred in landfills.

Today, we are in a different world. One in which any return to the sort of urgency with which our state housing policy was once pursued would not involve wood and other non-metallic materials put together on-site by hand, but rather an approach more like that of the aircraft factory.

There would of course be scope for cosmetic changes to mass-produced, monocoque steel houses, such as different sorts of exterior wood cladding.

More substantively, the upper part, normally half the length of the lower part, could be moved to the middle if desired rather than at one end, or rotated by 90 degrees. Two lower parts could also be combined to form a 130-square-metre, L-shaped house. Two lower parts could also be bridged together by a 12.5- metre upper part to form a 195-square-metre house. Such combinations would be interesting!

But the upper and lower parts — or more precisely, the 6.25 and 12.5-metre modules — would otherwise be standardised for mass production.

In this way, we would realise the idea of the house as a ‘machine for living in’: the idea of the house as an affordable appliance rather than an object of speculation and scarcity.

A ‘machine for living in’ that is made as cheaply as possible, like vehicles and appliances, using modern efficiencies and engineering for mass production rather than shortcuts.

Such a house might conceivably turn out to be as cheap, per square metre, as the Expanders offerings: but with a government-guaranteed CCC.

Even on the flat, the development of tiny homes and small houses has been stymied by “opaque planning rules” which have stymied innovation, standardisation and progress, as well as actual construction. Many tiny homes are built “under the radar” as a result, mounting them on wheels, jacking them up and taking the wheels away I suppose. And perhaps with illegal connections to services as well,

But in any case, not as many as there could be if the rules were not opaque.

For instance, in some council areas such as Tauranga, a tiny home counts as a single dwelling even when it only has one bedroom, and therefore isn’t allowed if you have exceeded the number of dwellings per section.

The Labour Government repealed parts of the Resource Management Act (RMA), widely regarded as dysfunctional and an obstacle to getting things like housing done, in August 2023, replacing them with the Natural and Built Environment Act (NBA) and the Spatial Planning Act (SPA). These two new Acts were the products of years of work on developing a better system. Also in the pipeline was the Climate Change Adaptation Bill (CCAB).

Previously, in 2021, the Resource Management (Enabling Housing Supply and Other Matters) Amendment Act specified that up to three dwelling units of up to three storeys could be built on most sections, or more precisely, that councils had to amend their District Plans in such a way as to permit this. These amendments were being worked on as of the election.

The incoming National Party-led coalition has committed itself to the repeal of the NBA and SPA and the reinstatement of the RMA, which they propose to replace with laws of their own design, though admitting that this will take another three years of work.

Some have expressed concern that these flip-flops will not do anything to speed up the production or consenting of new houses, but will simply prolong the agony, documented for Queenstown in a recent Lakes Weekly Bulletin article by Sue Fea called ‘Frustration boils over consenting delays’.

All in all, I wish that the previous government could have got more runs on the board via the development of easily manufactured designs for small houses, and actual schemes to crank up production of these ‘machines for living in’, rather than long-winded legislative reforms that the new government is simply pledged to repeal.

As a postscript, Chris reminds me that the small house has long been a topical issue in architecture. The small house was, for instance, a preoccupation of some of our most influential mid-twentieth-century architects, such as Bill Wilson and Ernst Plischke, and, earlier still, of the German ‘New Objectivity’ movement via the concept of the Existenzminimum, the minimum that is required for a dignified existence, as opposed to mere survival.

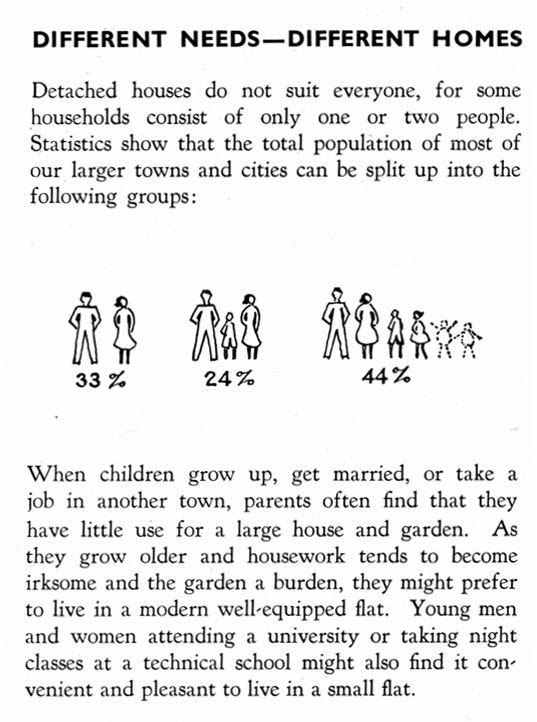

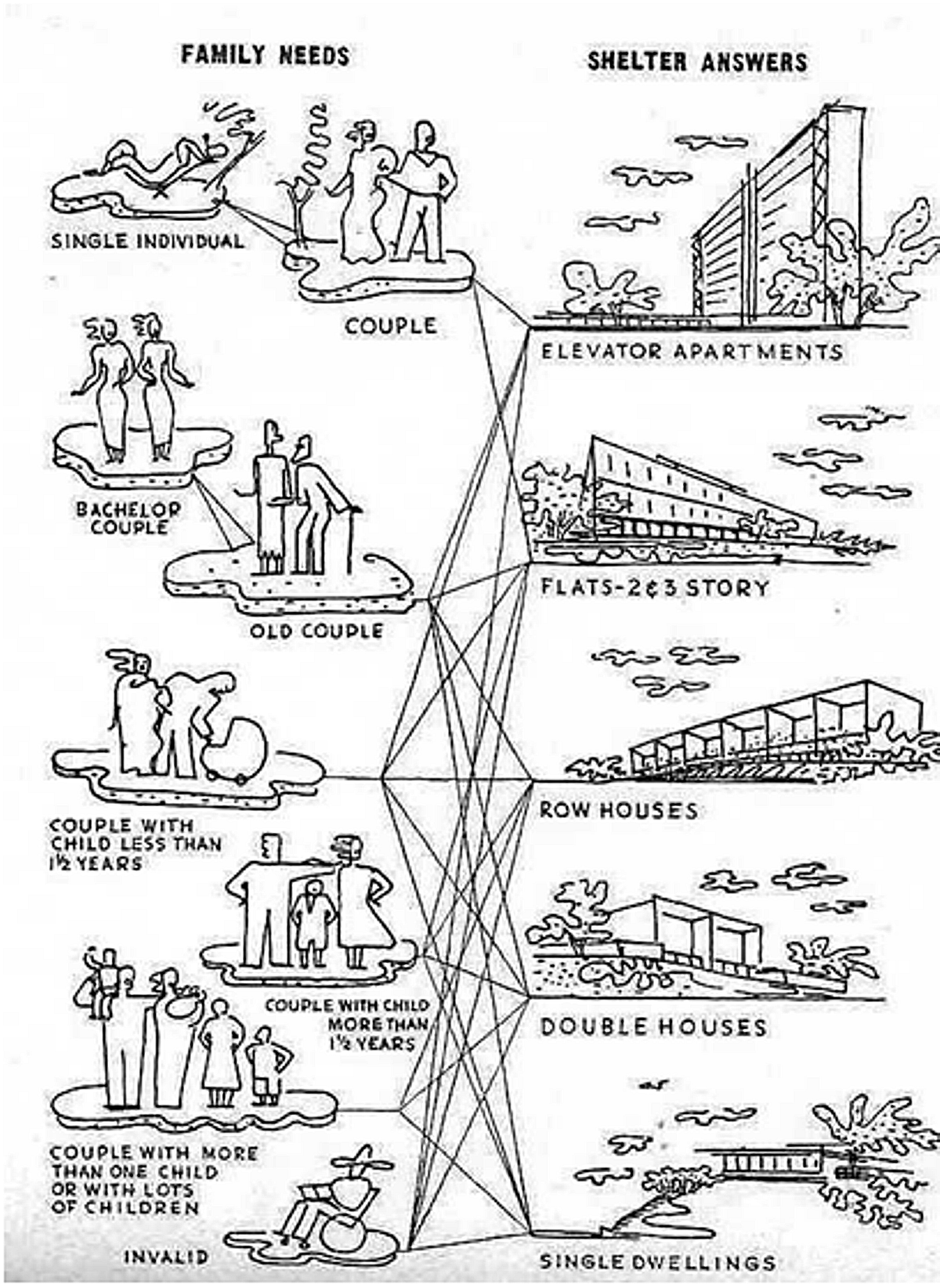

Among other things, the small house was seen as a good way of addressing the fact that a three-bedroom bungalow did not suit single people and smaller households. That point is made in the following period pieces, which appeared in print in the New Zealand of the 1940s and 1950s, respectively.

Such a long history makes it all the more surprising that there was not more progress in this area under the last government.

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive free giveaways!